On May 3rd, 2017, the International Space Station was traveling over the Pacific Ocean when a telescope on board noticed a new star in the sky. By the time the space station completed a lap around the Earth, 92 minutes later, the star had disappeared.

What looked like a star was actually a flash of light, and the telescope that saw it was named MAXI. Within minutes, MAXI sent an alert to NASA ground stations, which relayed the message to the MAXI team at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. One of the team members emailed me to let me know. I read the message at 6:30pm in Pasadena, alone in my office. With shaking fingers, I called my advisor’s cellphone. This looked like what we were after: an explosion in another galaxy marking the catastrophic death of a massive star.

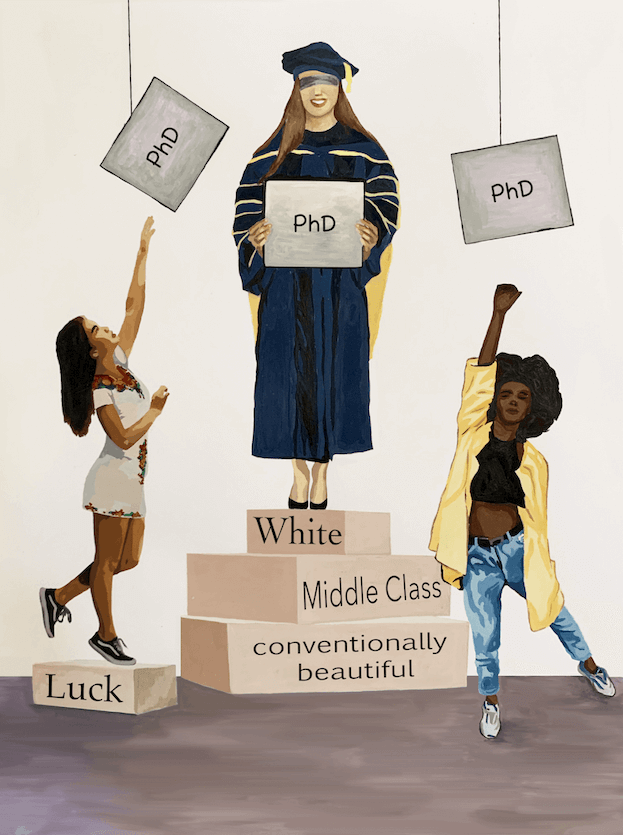

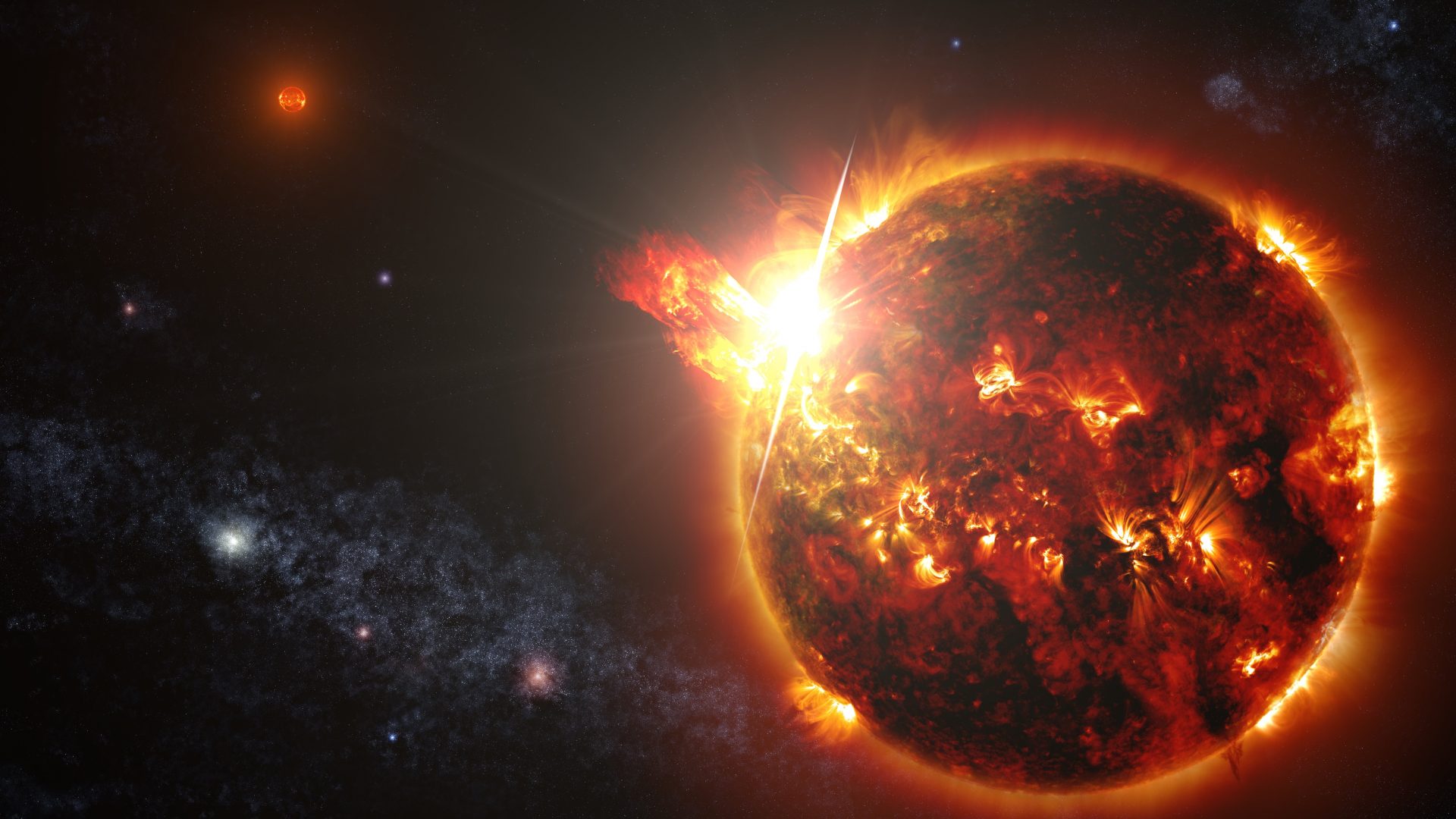

Artist's impression showing a red dwarf star emitting a series of powerful flares which can be observed billions of miles away on Earth.

S. Wiessinger, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

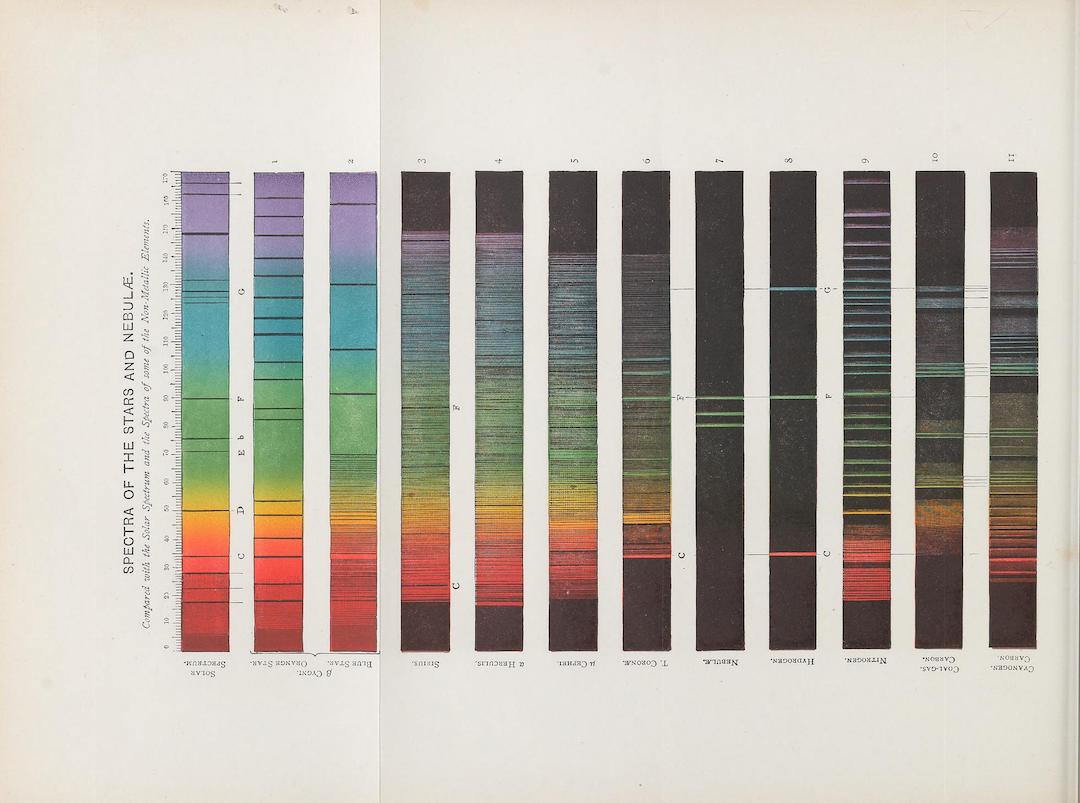

The night sky is dynamic: stars explode in distant galaxies and appear to our telescopes as flashes of light. Astronomers act like detectives, gathering evidence to learn how stars live and die. A detective might collect fingerprints, witness testimony, and camera footage; an astronomer collects different colors of light, most of which are invisible to human eyes. In fact, the colors of light we can see with our eyes are just a tiny fraction of the colors in the universe: the full rainbow extends to microwaves and radio waves on one end, and X-rays and gamma rays on the other.

Each of these colors opens a different window on to the universe. If your eyes could see X-rays, you would see heat and violence: matter falling into black holes and swirling around stars so dense that a teaspoon would weigh more than all the human beings on Earth combined. If you swapped your X-ray eyes for radio eyes, you would see what looks like a sky full of stars—but each “star” would actually be a distant supermassive black hole driving powerful jets. In astronomy, telescopes are our eyes: we use radio telescopes to see radio waves, X-ray telescopes to see X-rays, and so on. We need telescopes to see visible light, too, for details and magnification beyond what our eyes are capable of.

To choose a telescope, you have to think carefully about your hypothesis. In this case, we were looking for evidence of an explosion. An explosion would have plowed into its surroundings, heating up gas and dust. In its wake, electrons would spiral around magnetic field lines and emit radio waves. So, we needed a radio telescope: the Very Large Array (VLA), a group of 27 dishes out in the desert of New Mexico, each 10 stories tall and as wide as a baseball diamond. My advisor and I frantically wrote a request to use the telescope, and the VLA team responsible for handling last-minute emergencies like this gave us the green light. I worked out what exactly the telescope should do and uploaded the directions to an online interface, terrified that I would make a mistake and direct all these preeminent dishes to point at the ground for an hour. Two days later, I got an email saying the observation was done. When I checked the log I realized that it had happened early that morning. So strange to think that while I was asleep, these enormous dishes had received my request, and swiveled to the sky as one big eye!

With the VLA data in hand, we narrowed down the possibilities of the origin of the flash, but to pin it down precisely we needed another telescope: the 200-inch Hale Telescope at Mount Palomar, a few hours’ drive from Caltech. When I arrived, I checked into The Monastery, a yellow cottage tucked in fir trees where astronomers have been staying since the observatory was built in the 1930s. I chose my room from the floor plan on the chalkboard. With the room comes a small door in the side of the dome that houses the telescope, a dome almost exactly the size of the Pantheon in Rome.

That night, I sat in the dome with the telescope operator. When the patch of sky I wanted emerged over the horizon, I entered the coordinates and said, “We’re ready to slew to the next target.” “Slewing,” said the telescope operator. Through the door, 530 tons of steel glided along gears and pointed, settled, stopped. “Target is in the slit.” I set the exposure time to fifteen minutes, clicked “Go,” and as light from the distant universe fell on the 200-inch mirror, our camera was recording.

The author chilling with the Very Large Array, a series of dishes in the New Mexico desert that scientists use to peer into the depths of space.

Anna Ho

It turns out that our hypothesis was wrong: the evidence suggested that what MAXI saw originated much closer to home, in the atmosphere of a nearby star. In that star’s atmosphere, magnetic field lines are breaking apart and snapping together, and this can make flashes. I had thought that we were witnessing the death of the star, but instead we were witnessing vigorous life.

I was disappointed, and when my advisor said to publish the results in a scientific journal, I stared at him. “But we don’t have anything to say,” I said, meaning that we hadn’t found what we were looking for. He was surprised at my surprise. “This is the first time anyone’s systematically investigated these events!” he said. “No one had any idea what they were!” MAXI finds a lot of mysterious flashes, he said, and this is only the beginning of our investigation. He said that in his experience, when you’re just starting to explore a new phenomenon, you’ll learn that there are many different species that appeared at first glance to be the same thing. Sure, we now know that some of these MAXI flashes are flaring stars—but who knows about the rest?

Furthermore, he said, it’s not all about the result; a good research project for a graduate student is a lesson in the scientific process. The MAXI investigation was an exercise in thinking carefully about the telltale signatures of stellar death, making a plan for using different telescopes, and conducting and analyzing those observations. I posed a question, designed an investigation to answer that question, and learned the technical skills to execute the plan.

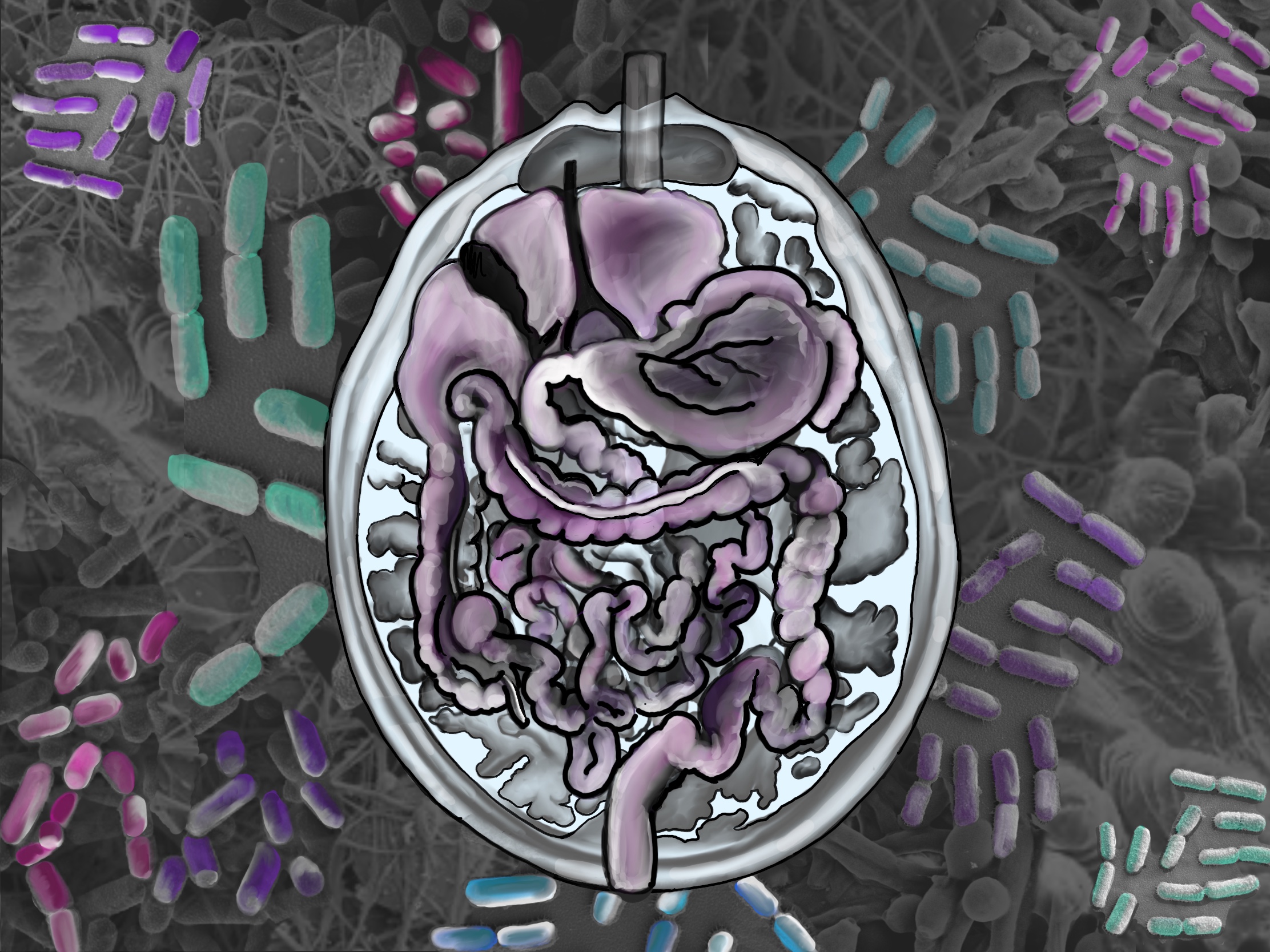

Now, I see that this project was a prelude to my thesis. Over the next three years, I will focus on a particularly energetic and elusive class of stellar death. The idea is that, in rare cases, a star explodes and leaves behind a rapidly rotating black hole. Rarer still, this black hole can launch a jet of relativistic matter. We are exploring these “engine-driven” explosions using a network of robotic telescopes around the world and in space, centered at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory. Our discoveries will teach us how matter behaves in conditions too extreme for our laboratories on Earth.

This is a difficult project because engine-driven explosions are rare. Every night, the robotic telescope at Palomar will flood us with a million candidates, and we have to sift through them to find something that might happen a few times a year, if at all. In preparation, I developed a set of automatic filters, which will block all but the most promising candidates. Integral to this filtering system are lessons I learned from my prelude projects, including the MAXI investigation: strategies to prevent flaring stars from fooling us.