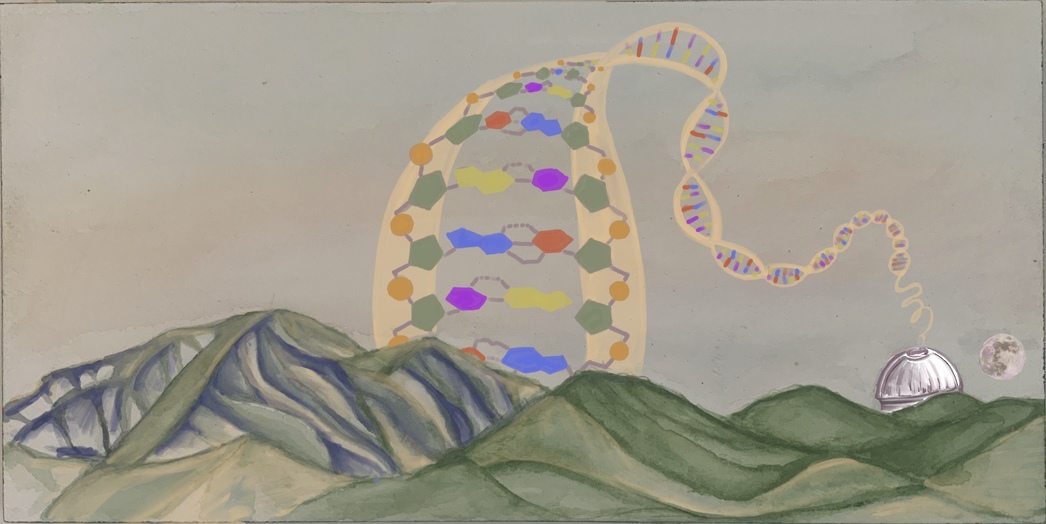

Illustration by Sarah Zeichner for Caltech Letters

The year was 2003, and the first human genome had been sequenced.

By almost every metric, it was an extraordinary achievement. The completion of the Human Genome Project provided a starting point for scientists to study the “blueprint for building a person”. Pharmaceutical companies suddenly possessed a genetic chart to design more targeted medicines. Archaeologists gained a roadmap to compare human genomes through the ages. Biologists acquired a lodestar to locate the genes governing health and behavior. The floodgates of the genomic era had officially opened. But the project also revealed a mystery.

In the 1990s, scientists estimated that the Human Genome Project would unveil 100,000 human genes. But the sequencing results revealed a stark reality: humans only have 20,000 genes—10,000 fewer than a water flea. It seems remarkable that humans—with our fancy bipedalism and oversized brains—could have fewer genes than a microscopic crustacean.

A lot has changed in the two decades since the Human Genome Project. The technology to sequence genes has gotten cheaper and faster. The first human genome sequence cost three billion dollars, involved thousands of scientists, and took 13 years to complete. Today, sequencing machines can read a human genome in less than a day for a few hundred dollars. But technology is not a substitute for knowledge, and scientists still don’t fully understand how the genome works.

The Broad Center for the Biological Sciences at Caltech.

Photo by Suzy Beeler

Nestled in the back corner of the Broad Center for the Biological Sciences at Caltech, our research laboratory aims to understand how genomes encode and express information. To find us on campus, look for the cubic building made from metal and travertine, with sweeping views of the San Gabriel mountains. On a clear day many months ago, before the pandemic confined us to untidy apartments, we could see Mt. Wilson Observatory from our offices. Its white telescopes dot the mountain’s summit, silhouetted against the rising sun. Inside the lab, our benches are cluttered with liquid-filled bottles and metal pipettes.

We study genomes, in part, because of the impact on our impressionable young minds when the Human Genome Project made national news back in 2003. The structure of DNA had been established fifty years earlier, thanks to herculean efforts from Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and others. Our understanding of genomes came a long way in those 50 years, from structure to sequence. But we know that there is more to learn.

About 500,000 human genomes have been sequenced since 2003. Sequencing machines are now commonplace at universities. Humming on tables, they look like space-age computer systems, with touch screens and tiny, pneumatic tubes. DNA is extracted from living cells, trillions of copies are made using a technique called PCR, and the copied molecules are loaded (carefully!) into the machine. A few hours later, after the humming subsides, an interminable string of characters appears on the screen, made up of four letters: A, T, C, and G.

All genomes on earth are made up of these letters, called nucleotides. Each letter is a unique molecule—adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine—that links up to the others, forming a minimal alphabet. With these four letters, our cells construct words, or—in the context of biology—genes.

Much as a Xerox machine can make thousands of copies from a single document, genes are converted to messenger RNA in a process called transcription, which then serves as a template to build proteins. The human genome encodes about 20,000 genes, which in turn produce proteins that fend off viral invaders, manage blood sugar levels, and everything in between.

This short animation shows how transcription happens.

But we cannot “see” these dynamic changes with a DNA sequence. The order of letters in a genome tells us nothing about how a gene is controlled in the molecular confines of a cell. Gene expression is dynamic and changing. Genes are turned on and off as proteins are needed, and these changes over time may explain how genomes can give rise to the most beautiful of lifeforms. In other words, it may explain how we are human, despite a trifling 20,000 genes.

We study how genomes are controlled because we want to understand ourselves. In doing so, we are building upon more than 80 years of experimental history.

In the 1940s, Jacques Monod and François Jacob, frantically working in a little laboratory in the Necker neighborhood of Paris, found that cells control protein numbers by turning genes “on” or “off”. Though their results seem obvious today (the best results always do), they shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work.

Genes are regulated by proteins called transcription factors, of which there are two types: activators, which bind to DNA near the start of a gene and increase the amount of mRNA copies made from a gene, much like loading more paper into a Xerox tray, and repressors, which decrease the amount of mRNA copies. Transcription factors hold dominion over the genome, controlling when each gene gets to make its Xerox copies.

Jacob and Monod’s findings provided a potential solution to the question that arose from the first human genome sequence, 60 years later. Perhaps an organism’s complexity is dictated not by how many genes are present in a genome, but rather by how those genomes are controlled, over time, by transcription factors. To build upon the work of our scientific heroes, our lab at Caltech wanted to determine which type of transcription factor—activator or repressor—regulates each and every gene. To test our experiments, we decided to start with a small genome. We turned to a bacterium, Escherichia coli.

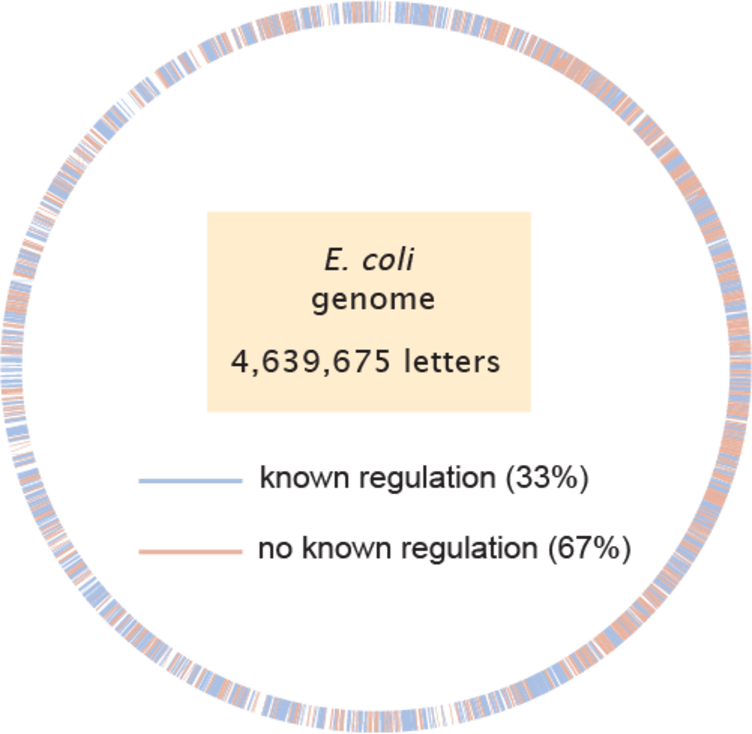

In the grand order of nature, E. coli is relatively simple, containing 4,000 genes and 200 transcription factors. But, despite its meager size, we still do not know how two-thirds of its genes are regulated.

The E. coli genome contains about 4.6 million nucleotides and 4,000 genes. In this diagram, genes that have known regulation (which means that we know which transcription factors regulate them) are marked in blue. For most genes (roughly two-thirds), we have no idea which transcription factors regulate or control them (marked in red).

Diagram by Niko McCarty

We knew that if we ever wanted to understand how even a small bacterial genome is regulated, a new experimental method would be needed. So we created one.

When Nathan Belliveau joined the lab, a few years ago, his objective was simple: find an easy way to determine how genes in E. coli are regulated.

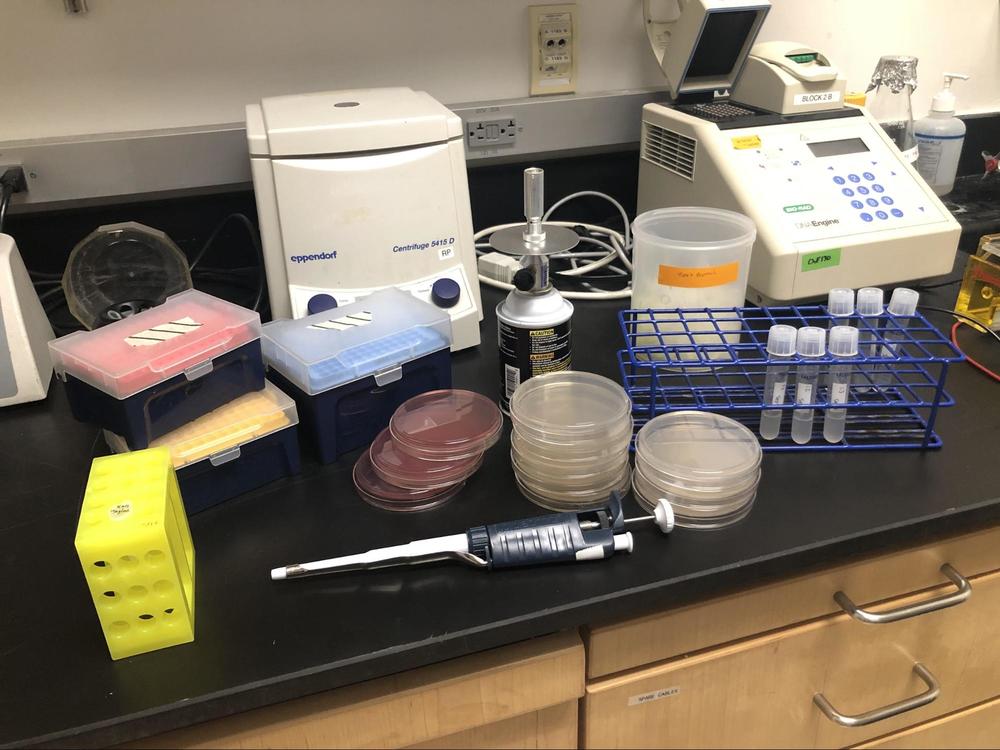

Sitting at the bench, he harvested genetic material from E. coli and loaded the DNA into a sequencer. After a few years—and hundreds of trials—he reported the foundations of a radical method that would eventually enable our laboratory to figure out which transcription factors regulate hundreds, or thousands, of genes at a time. Nathan left the group in 2017, PhD in hand, and flew to colder climates. Bill Ireland and Suzy Beeler (an author of this article) took over the project.

They, too, spent years agonizing over the method. After using thousands of tubes of DNA and covering their benches in teetering stacks of bacteria-streaked agar plates, Bill and Suzy managed to extend Nathan’s findings to more than a hundred genes. In the process, they refined a powerful method that lends deep insights into the intricate, molecular machines that regulate genomes.

Here’s how the method works.

We begin by literally mail ordering short sequences of DNA—the regions immediately in front of a gene—where transcription factors typically bind. A computer helps us design mutated versions of each DNA sequence, randomly changing the letters until we have thousands of variants for each sequence. A company in San Francisco takes our digital letters, creates physical copies, and ships them in a little plastic tube to our laboratory. We then place these synthetic pieces of DNA inside of E. coli cells, and use a modified version of DNA sequencing to determine whether each “letter” change made a gene produce more or fewer Xerox copies.

If a DNA sequence produces very little RNA inside of the cell, this suggests that the letter change (or mutation) blocked transcription; it choked up the Xerox machine. It also indicates that an activator was probably binding to that DNA sequence, and the mutation prevented it from doing its job. Some mutations, however, increase the amount of RNA produced from a DNA sequence, suggesting that the mutation is preventing a repressor from binding.

By analyzing this data and running it through mathematical models, we can determine whether each gene is regulated by an activator or repressor, how many transcription factors regulate each gene, and where those transcription factors actually bind.

In other words, we can map the genome’s regulatory networks.

A bench in our laboratory, where this work was performed

Photo by Suzy Beeler

After performing this experiment on more than one hundred genes, we made some startling discoveries. In one case, we found a transcription factor with dual activity: it activated the transcription of one gene while repressing the transcription of another. We also identified transcription factors that are only active in certain environments; when E. coli is grown in the presence of a sugar, for example, a transcription factor called GlpR represses a handful of genes. Without the sugar, GlpR doesn’t work at all.

In our opinion, this study marks a major advancement in genomic research. But it didn’t come for free.

Throughout the last five years, we have failed repeatedly. We have mislabeled tubes and used ethanol instead of water to dilute DNA. We have dropped flasks, shattering glass and spilling bacteria on the floor. We have been frustrated, again and again. But we continued on, inching closer to mastery over the molecular wiring of genomes. In the future, we’d like to extend this work to other organisms; perhaps even humans.

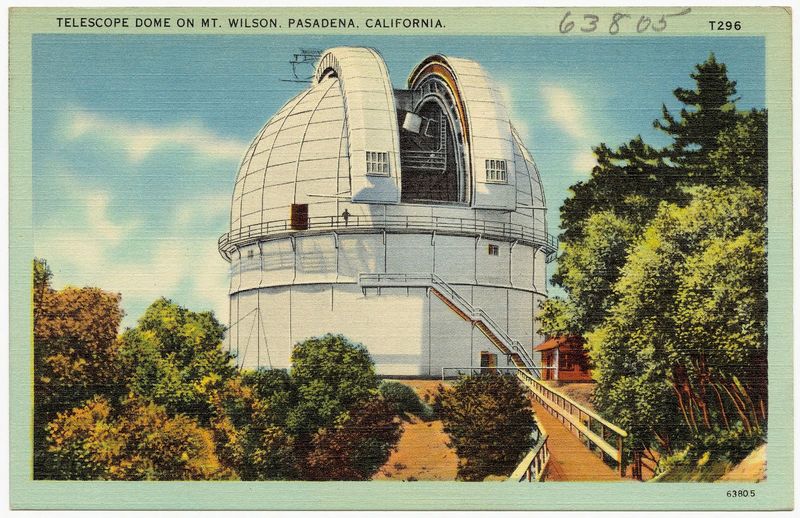

Postcard of telescope dome on Mt. Wilson

Tichnor Brothers, hosted on Wikimedia Commons

From our laboratory on Caltech’s northern end, we can no longer see the lights of Mt. Wilson Observatory. A construction site—soon to be a neuroscience research building—obscures our view. But we still think about those twinkling lights, emitted from distant telescopes where astronomers like Edwin Hubble and George Ellery Hale recorded the stars, measured the speed of light, and mapped our place in the cosmos.

Here, in our laboratory in the mountain’s shadow, we are looking down into cells, rather than up at the stars. We are engaged in work that could fill a lifetime: decoding the language of genomes. With time and patience, we may yet understand how a simple molecule with only four letters is able to give rise to biology in its myriad of beautiful, chaotic forms.

This article is based on a study, published in eLife.

Ireland WT, Beeler SM, Flores-Bautista E, McCarty NS, Röschinger T, Belliveau NM, Sweredoski MJ, Moradian A, Kinney JB and Phillips R. “Deciphering the regulatory genome of Escherichia coli, one hundred promoters at a time.” eLife (2020).