Illustration by Siobhán MacArdle

If you’ve ever drunk wine with a wine aficionado (don’t call them snobs!) you’ve probably heard them describe what they smell—maybe dark fruits, baking spices, freshly cut grass—and also note whether or not the wine has tannins and how much. To understand what people mean when they talk about tannins in wine, we can start with an experience that has nothing to do with wine: drinking oversteeped tea. When you finally take a sip of the tea you forgot about 20 minutes ago, your soothing afternoon ritual is now stripping the inside of your mouth of all its moisture, causing you to recoil and shiver. You are feeling astringency, like your mouth is being dried out. This astringent experience is caused by molecules called tannins—chemicals found in many foods such as tea, dried fruit, and chocolate, but perhaps most famous for their presence in wine. In a good wine, tannins cause a more subtle drying sensation than in your forgotten oolong, providing complexity and structure, which adds another dimension to the tastes and smells we get from these chemical solutions.

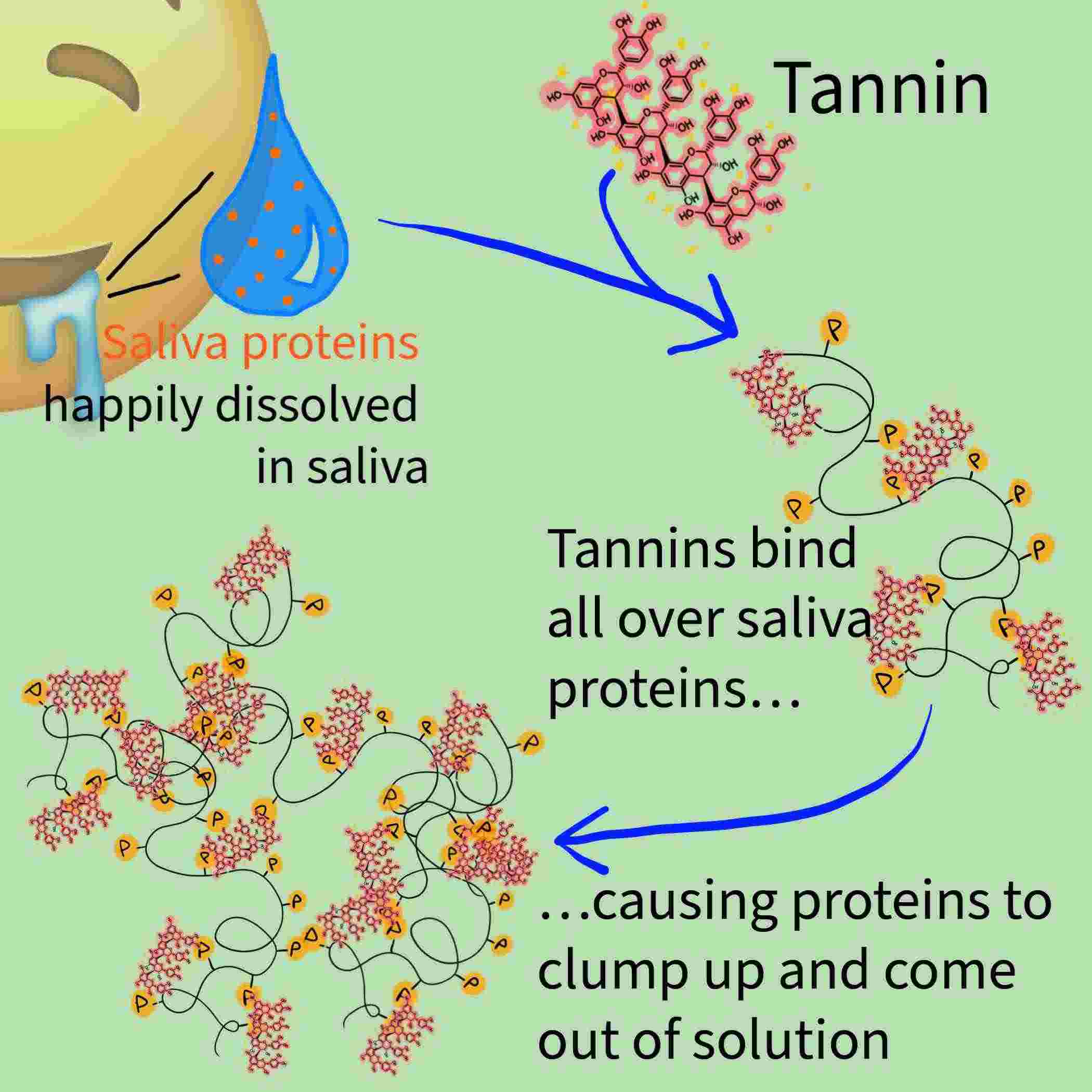

The astringent sensation caused by tannins makes your mouth feel dry. However, tannins aren’t actually drying out your mouth–this is just how our brains perceive the interaction between tannins and our saliva. The chemical structure of tannins makes them particularly good at sticking to things and clumping them up. Think of tannins like those burrs that get stuck to your clothes when you go for a walk in nature. Just like burrs, the interactions that tannins make are nonspecific; they will stick to many different types of molecules (whatever they happen to bump into). In our mouths, they bump into saliva proteins. The saliva in our mouths is full of proteins that keep our digestive tracts lubricated, but after taking a sip of wine or that neglected tea, the tannins in these beverages will bind to our saliva proteins and clump them up. All clumped up, these proteins are no longer dissolvable in our saliva and they become more like tiny pieces of sand—not big enough to see, but big enough to feel. We experience the friction of these tiny bits of sand-like protein-tannin clumps as astringency, or dryness, in our mouths.

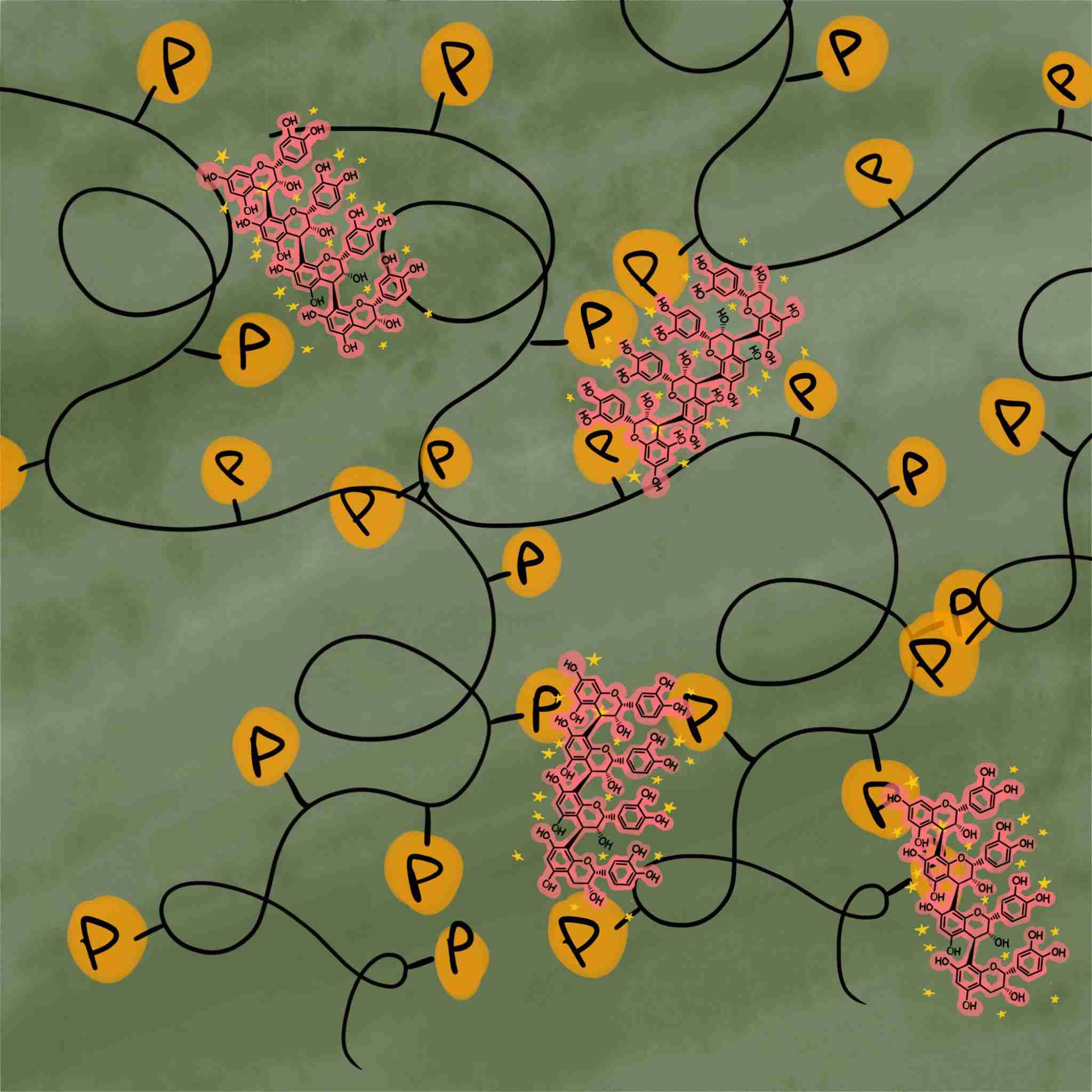

So, what is it about tannins that makes them so prone to clumping? Tannins are a subcategory of a broader class of molecules called polyphenols. Phenols are carbon rings decorated with oxygen atoms and polyphenols are many of these phenols joined into one big molecule. Phenols have many double bonds, which carry lots of negatively-charged electrons that aren’t married to any particular atom. The oxygens on the phenols are electronegative, which means they pull electrons toward themselves. This combination of lots of double bonds and lots of oxygen atoms creates many areas of polarization in the molecule, which means certain parts carry slight negative charges and other parts carry positive charges. This polarization makes the tannins more likely to form attractive interactions with things that they bump into than if they were neutral molecules.

For example, when a negatively-charged part of the tannin comes into contact with another molecule, the negative charge will repel the electrons of that molecule, causing that part of the other molecule to be slightly positively charged. Now you have a slight negative charge in the tannin and a slight positive charge in the other molecule, which causes attraction! These attractions are called van der Waals forces and they are relatively weak, way weaker than the bonds that bind atoms in molecules: if bonds between atoms in a molecule are superglue, van der Waals forces are maple syrup. Long story short, tannins are sticky1. They are likely to glom on to chemicals that they find, and when we’re talking about tannins in wine, the largest class of chemicals that they find are the proteins in our saliva.

Our saliva proteins are well equipped to interact with tannins as well. All proteins are made up of a combination of 21 different amino acids stuck together in a long chain and folded into a unique structure. The proteins in our mouths contain a lot of a particular amino acid called proline. Proline is special because it forces a kink in the protein structure. So lots of prolines means lots of kinks and bends in the protein, which makes for a disordered squiggly mess. This open and unstructured shape of the proteins in our saliva provides many spots for tannins to bind. Although there are no specific bonds that happen between tannins and saliva proteins, both are perfectly suited for many non-specific interactions, thus resulting in clumping.2

The interaction between tannins and saliva proteins.

Illustration by Siobhán MacArdle

But why did our saliva evolve to have all these squiggly proteins? Let’s imagine that we didn’t have these proteins in our saliva—the tannins would have nothing to clump to in our mouths and would make it to our stomachs and intestines all on their own. There, they would find the important digestive enzymes—chemicals that we need to get nutrients from our food. If free tannins made their way to these enzymes, they would bind and clump them up, taking them out of commission and disrupting our digestion. You might have experienced this if you stubbornly drank that over-steeped cup of tea anyway and gave yourself a stomach ache. We probably evolved to have these squiggly proteins in our saliva as sacrificial tannin sponges to protect our digestive enzymes from the tannins in our diet.

There is immense range in the levels of tannins in wine, and wines are commonly described as having low, medium, or high tannins. If you start paying attention to the level of astringency you experience from certain wines, you might develop a preference for wines with a particular level of tannins. And then you might actually have an answer at the wine store when they put you on the spot with, “are you looking for anything in particular?”

Most of the tannins in wine come from the skins of the grapes used to make wine3. These skins and the winemaker’s choice of what to do with them are how we end up with wines of such varying tannin levels. If the winemaker chooses to include the skins during fermentation, the tannins dissolve into the grape juice and the resulting wine will have tannins. The extent of tannic character depends on the length of time the winemaker chooses to keep the skins around. Just like a tea bag, the longer the skins are “steeped,” the more intense the astringent experience caused by tannins will be. In addition to time with the skins, the other variable affecting tannin levels is the type of grape. Certain grapes are thicker-skinned than others, so they will impart more tannins to the wine than wines made from grapes with thin skins. Pinot Noir, for example, is notoriously thin-skinned, so these wines will always be low in tannins. Nebbiolo grapes, on the other hand, contain a lot of tannins in their thick skins, so wines made from these grapes will have an intense tannic character.

Even within a grape variety, there can be variation in the levels of tannins depending on the conditions used to grow the grape. Tannin molecules may serve as a sort of “sunscreen” for the grapes, absorbing UV rays from the sun that could be damaging to the grape cells (all those double bonds in tannins that were mentioned earlier are also great for absorbing UV radiation!). Thus, grapes that are grown at higher altitude and in more direct sunlight, where they are more prone to harmful levels of UV radiation, will produce more tannins to protect themselves than grapes grown in the shade and at lower elevation.

You might have noticed that red wines tend to have more tannins than white wines. This is because traditionally, red wine is made from red grapes and the skins are included in the fermentation, while white wine is made from white grapes and the skins are separated out before fermentation. With no skins around during fermentation of white wine, there are no tannins to be had. Rosé is made from red grapes, but the skins are separated before fermentation, as they are for white wines, which is why rosés are lighter in color and tannins than red wines4. A fun tasting experiment is to try to find a red wine and a rosé from the same producer of the same grape (something to ask about the next time you’re at the wine store!). Tasting these wines side by side will give you a sense of what flavors and sensation come from the grape juice vs. the grape skins.

There is a fourth variety of wine growing in popularity in the US called “orange wine” or “skin contact white wine.” Just like how rosés are made from red grapes in the style of white wines, orange wines are made from white grapes in the style of red wines. That is, orange wines are made by fermenting white grapes without separating out the skins. Therefore, these wines have some of the color and tannic complexity of red wines, with the brightness and acidity of white wines. They come in varying shades from light yellow to deep amber depending on how long the skins were kept mixed into the juice during fermentation. You can ask at your local wine store how much skin contact a particular orange wine has. If they say 6 months, you’re getting a more tannic and dark orange wine, whereas if they say 24 hours, you’ll be drinking something more akin to a traditional white wine.

You don’t need to know any of this to consume and enjoy the complexity that tannins bring to wine, but it is fun to think about how much more our mouths can do than just taste. Because the drying sensation we get from tannins happens in our mouths, we often talk about tasting them; however, the sense we use to detect tannins is actually touch. By feeling the clumping of saliva proteins in your mouth you’re getting a glimpse into the story of the wine, starting from the conditions of the grape growing in the vineyard, through the fermentation of the grape juice, and finally, into the bottle. And understanding the mechanism behind our perception can help us bring awareness to the tannins and other features of great wine. You might get so focused that you start to notice differences in the astringency feeling you get from some wines versus others. In fact, people might describe different types of tannins in wine as soft, fine or even velvety.

Finding tannins in food, even beyond wine, can be an effective mindfulness practice. The next time you eat or drink, try to distinguish between what your mouth is feeling versus what you are tasting, and you’ll likely discover many more tannins in food!

Footnotes

1: Polyphenol molecules are also what gives peated whiskey its smoky taste, which is another example of how sticky these molecules are. In this case, the polyphenols come from the peat that is burned to dry the barley before fermentation. They stick to the barley throughout fermentation, distillation, and decades of aging, allowing us to taste that peat smoke many many years later.

2: This is called “aggregation” in chemistry-speak.

3: There are some tannins that come from the seeds and stems of the wine, but they are often less prominent than the skin tannins. If a wine is described as “whole cluster”, that means it was fermented with the stems and therefore will have stem tannins. Barrel-aging is another source of tannins—if a wine is aged in barrels, especially new barrels, it will extract tannins from the wood.

4: The compounds that give wine most of their color, anthocyanins, are also found in the skins of grapes.