It’s a bleary-eyed Tuesday morning in the lab. Or a bustling Thursday evening. Or a quiet Saturday afternoon. The day doesn’t matter. I’m staring at a rack of tubes on my lab bench—a familiar sight for a synthetic biologist. Each tube holds a teaspoon of broth, milky-opaque with the favorite bacteria of synthetic biologists worldwide, Escherichia coli (E. coli). I’m fixated by one of these tubes, because it doesn’t make sense.

Normally, E. coli has a snot-like slightly greenish-yellow color, but I’ve engineered these particular E. coli to glow red. They are a rich scarlet, like a particularly foul-smelling strawberry lemonade. I’ve grown them many times, in many tubes, and they’ve always been the same strawberry pink. But this tube is a pale shadow of the others, more of a peach blush than a scarlet-red. It isn’t quite the color of normal E. coli, but it’s well on its way there.

What happened?

Three tubes of E. coli. From left to right, the strawberry pink engineered E. coli, the mystery tube of E. coli, and a tube of normal E. coli.

Photo by Ren Marquez for Caltech Letters

All living things are made of cells (or, in the case of bacteria, a single cell) and all cells are machines. Wet, jiggly, sloppy machines, but machines nonetheless. While not quite the same as a programmable computer, a certain kind of biologist—a synthetic biologist, like myself—sees these biological machines as powerful, flexible marvels that are ripe for tinkering.

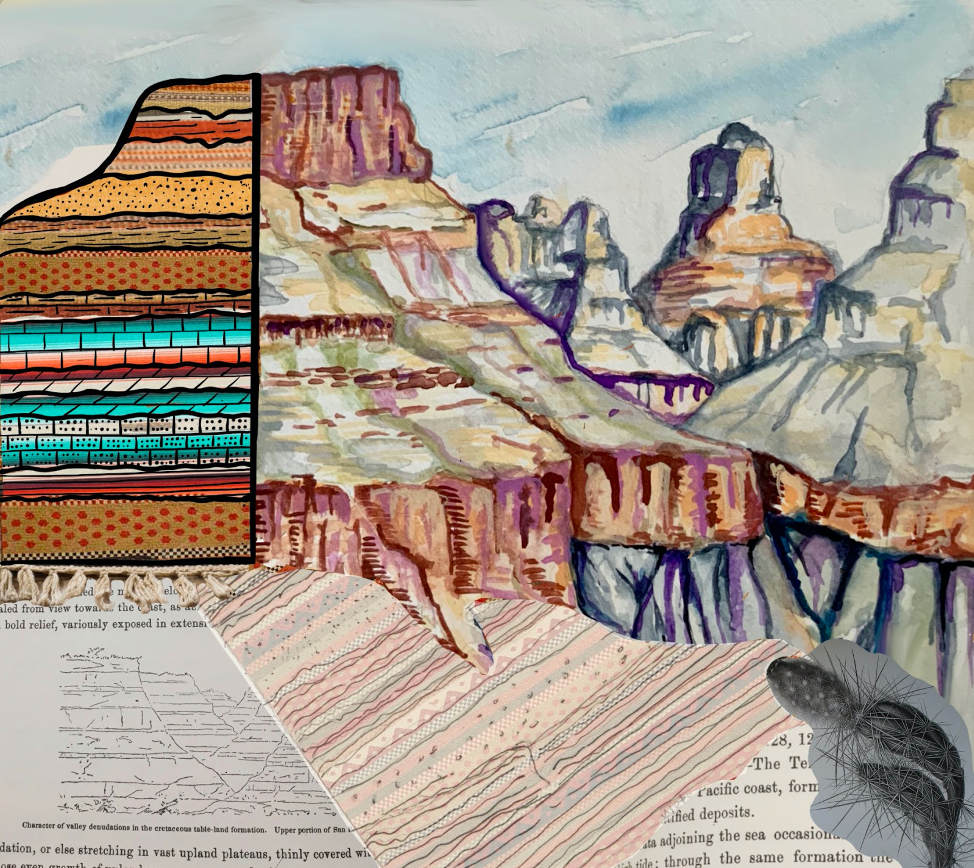

E. coli, in particular, is great for prototyping synthetic biology. Don’t be fooled by its microscopic size: E. coli is a complex machine, less like a watch than a molecular-scale industrial factory. The factory’s equipment—its sensors, robotic arms, conveyor belts—are made from proteins, which vary enormously in size, shape, and function. Some proteins are small machines that perform a single function, much like a tape measure or weigh scale. Others form massive complexes with equally complex functions, like an assembly line.

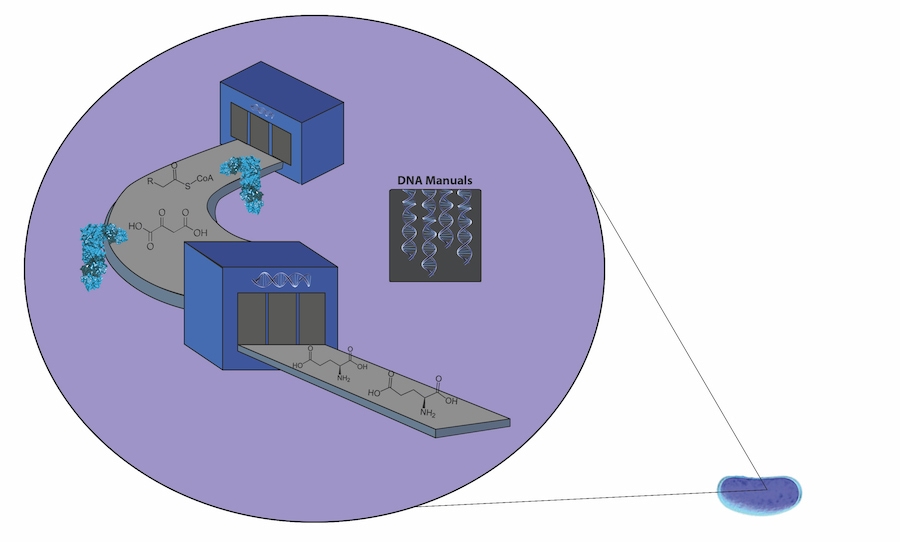

Every factory needs plans—blueprints, operating manuals, and company standards that dictate the factory’s structure and operation. Cells keep these plans in the form of DNA: long strings of four different molecules, called bases (A, T, C, and G), that make up the genetic code. Encoded in the cell’s DNA are the formulas for every protein that a cell can produce, as well as regulatory sequences that determine when to build each one, and in what quantity. We call each formula a gene, and the collection of all of E. coli’s genes its genome.

Cells function as molecular-scale factories. Here, this metaphor is portrayed literally: DNA is shown as manuals directing an assembly line of proteins in teal to produce different molecules.

Illustration by Tracy Lu for Caltech Letters

What makes E. coli spectacularly useful to synthetic biologists is that we can change its operating manual. Synthetic biologists can reprogram bacterial cells to respond to their environments, warning us of otherwise difficult-to-detect dangers, or to produce complex and useful chemicals. Insulin, for example, is almost trivially simple to make using an engineered cell and essentially impossible to make without one.

In theory, the process of engineering a bacterium to make a chemical is simple. First you make a DNA manual (a gene) specifying either a protein (like insulin) or a protein that makes a chemical you want. Then you insert that DNA into the bacteria’s genome so that when the bacteria grows, it will (hopefully) make whatever you’ve told it to.

That’s what I’ve done to my glowing-red E. coli—I’ve introduced a new set of instructions that tells the cell to crank out a protein that glows red, aptly called red fluorescent protein (RFP). This mostly worked, but in one test tube, my bacteria aren’t following their instructions.

The author holds three tubes of E. coli grown overnight. On the right is a tube of un-modified, natural E. coli. On the left are cells engineered to produce a red fluorescent protein (RFP). In between is a tube of cells that have been engineered to glow red, but are no longer producing RFP.

Photo by Ren Marquez for Caltech Letters

Like all metaphors, the bacteria-as-chemical-plant metaphor eventually fails. A critical difference between E. coli and a factory is that unlike a static factory building, E. coli builds almost (almost!) perfect copies of itself.

E. coli loves making copies of itself, as quickly as it can. Every one of its roughly fifty billion molecules works toward this end. Each E. coli can, if fed properly and kept at the right temperature, double its size and then split into two identical copies (with identical genomes) every twenty minutes.

Here’s the crux of my problem: red fluorescent proteins don’t help an E. coli grow faster. They don’t help it adapt to new threats, or take in energy more efficiently. RFP does nothing for an E. coli but glow red… and use up resources. Energy, molecular building blocks, and time spent making RFP are all resources that don’t go into making more E. coli.

In short, an E. coli cell that helpfully produces RFP grows more slowly than an E. coli cell that doesn’t.

Some back-of-the-envelope calculations will show us how bad the problem is. Imagine starting with a hundred red-engineered RFP-producing E. coli cells and one non-producing, “selfish” E. coli cell. The selfish E. coli divides every twenty minutes, doubling its population while the red E. coli grow at about 70% that speed, dividing every 25-30 minutes. At those speeds, the selfish population will double in size relative to the red population every eighty minutes. After 24 hours, only 3% of the cells will still be making RFP.

This is natural selection at work. In a mixed population, cells that produce the most offspring the fastest will eventually take over.

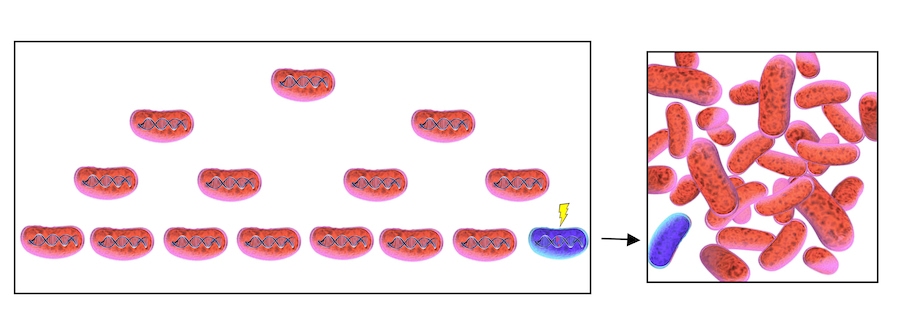

A single non-producing, cell (blue) appears in a group of RFP-producing cells (red). Over time, both kinds of cells reproduce, but the nonproducer cells grow faster. After five hours of growth, half of the cells are nonproducers. Natural selection favors the faster growth of the nonproducers, and given enough time, they will take over the population.

Illustration by Tracy Lu for Caltech Letters

One of my tubes has been overrun by selfish, non-RFP-producing E. coli, but there’s one more piece of this puzzle—where did they come from? Perhaps a selfish E. coli was hanging out on my lab bench and accidentally got in my tubes, but I keep everything sterile and use antibiotics to ensure that un-modified E. coli can’t grow in my experimental test tubes, so there should be no cross-contamination.

Enter mutation.

Every time a cell—any cell—divides, it has to make a copy of its genome. The replication machinery of E. coli is almost absurdly accurate, but it does occasionally make a replication mistake—either replacing, deleting, or inserting a base (A, T, C, or G)—which we call a mutation. Under normal conditions, E. coli only mutates about one out of every ten billion bases. The genome of an E. coli is around five million bases long (the equivalent of about 10 megabytes of computer-stored data!). This means that only once in about two thousand cell divisions will the bacterium make a single mistake.

On the other hand, there are many, many, many bacteria in a teaspoon of liquid broth, the size of a typical test tube. E. coli typically grows to a density of about five billion bacteria per teaspoon. By the time it gets to that size, the population as a whole has undergone ten billion genome replications.

Despite the incredible accuracy of E. coli’s DNA replication, the enormous number of divisions it undergoes means that any particular mutation is surprisingly likely even over a single day of growth. Crunch the numbers, and you will find that on average, every base in the E. coli genome will mutate approximately once in a test tube grown overnight. That means it’s quite possible that if there is a possible mutation that breaks the production of RFP, then at least one cell in a fully grown tube will happen to acquire that mutation. Once that happens, it’s only a matter of time before that mutant non-producer takes over the population.

This is evolution. Random mutations generate variation, which then gets a push from natural selection until the fittest mutants dominate.

Dividing bacteria occasionally make a mistake replicating their genome, which can break engineered function, illustrated by the blue cell with a lightning bolt. Mistakes are extremely rare, but there are so many bacteria in a tube dividing that breaking mutations are virtually inevitable. Once one RFP-producing cell has broken, selection pressure will cause that cell type to take over the population.

Illustration by Tracy Lu for Caltech Letters

E. coli are living, self-replicating machines. Synthetic biologists can program and engineer them for human purposes, but they are also wild, uncontrollable, and slippery-selfish. To program them, you need to understand the rules of evolution, just as an automotive engineer needs to understand how an engine works.

The evolutionary pressure to break human-made changes doesn’t only affect bacteria that are engineered to glow red; it applies to almost anything we might want a fast-growing organism to do. Very rarely do human needs and wants coincide perfectly with E. coli’s “need” to grow faster. Unless they do, those bacteria will always be under pressure to break human-made changes in favor of fast reproduction.

Understand that pressure, plan for it and around it, and you can make much more stable RFP-producing bacteria than I did.

Synthetic biology is a young field. We’re just now dipping our toes into a vast ocean of bioengineered possibilities: smart anti-cancer hunter-killer cells, chemical synthesis at eye-poppingly low prices, or medicines that grow on trees. We may be able to bring endangered species back from the brink, engineer crops to grow in especially stressful environments, or make plants that more efficiently convert sunlight into useful energy. All of these may be possible by co-opting the living machines around us to do things we want.

But evolution is always working in the background. Usually it serves to gum up the works of human projects, but always in perfectly logical ways that scientists need to be attuned to in order to work with it or around it. Otherwise, the life we engineer to do our bidding will always find a way to do what it really wants to do—grow and survive.