I was wedged in the 1.5-foot space between an airplane seat and the instrument bolted to the floor in front of me. Huddled in the tight space, I wrapped myself in multiple layers of warm jackets and braced against the constant chill. Outside, the wind howled as it whipped across the open doors of our plane, which sat on a cold runway in one of the southernmost cities in the world — Punta Arenas, Chile. In one hand I held a small flashlight and in the other a multimeter, a tool that serves like a doctor’s stethoscope to diagnose electrical problems. My lab-mate squeezed into the space beside me, awkwardly angling her arm inside our instrument’s electronics box as she tried to quickly yet carefully solder two wires together inside it. The power source on one of our instrument’s computers had failed and we had 6 hours left to fix the problem or we wouldn’t be able to collect any data during the next day’s flight. That flight would take us over Antarctica, a region of scarce scientific knowledge due to its remoteness and inaccessibility. We had only this one chance to collect key atmospheric data there; a chance that we were now very afraid we would lose.

The NASA DC-8 aircraft, our “home” for 26 days as we traveled around the world as part of the ATom Mission

Hannah Allen

When the computer went down we were in the midst of a series of flights that would quite literally take us around the world. I often hesitate to tell people about my graduate school research because of how cool this sounds; I feel just a little bit too much like I’m bragging. What we were doing is actually a key component of atmospheric chemistry, the field that I have chosen to devote several years of my life to studying. The series of scientific research flights I had embarked on is collectively dubbed the Atmospheric Tomography Mission, or ATom for short, and took place aboard NASA’s DC-8 aircraft. Our goal on the plane was to take measurements from around the world that could be used to understand how different chemicals form, interact, and transform in the atmosphere. Many of these chemicals comprise less than 0.00001% of the air, so our instrument is specifically designed to be able to detect these trace quantities of interesting compounds. We then compare our observations with what our lab studies and models tell us ought to be happening to assess our current understanding of the Earth’s atmosphere.

The ATom data we collected will address a whole host of scientific and societal questions. Because we sample the entire globe, we can discover how various emissions (e.g., from urban pollution or even wildfire smoke) from different countries react and move around, affecting the Earth’s atmosphere far from their origins. In particular, I study a class of compounds called peroxides to infer how much an air mass is able to chemically react, which provides insight into the type of chemistry each region undergoes. We also work closely with groups developing global chemical-climate models that simulate the Earth’s complex dynamics. These models allow us to investigate and predict how these emissions will alter the climate. Policymakers then use these predictions to assess the best strategies to mitigate climate change’s harmful consequences. For example, these models are why nations agreed to limit global warming to less than 2 °C in the Paris Climate Agreement. The measurements we collected during ATom will validate and improve the models, allowing politicians to make better decisions regarding emissions and the future climate.

Flight path taken by the DC-8 during the ATom Mission. We quite literally fly around the world

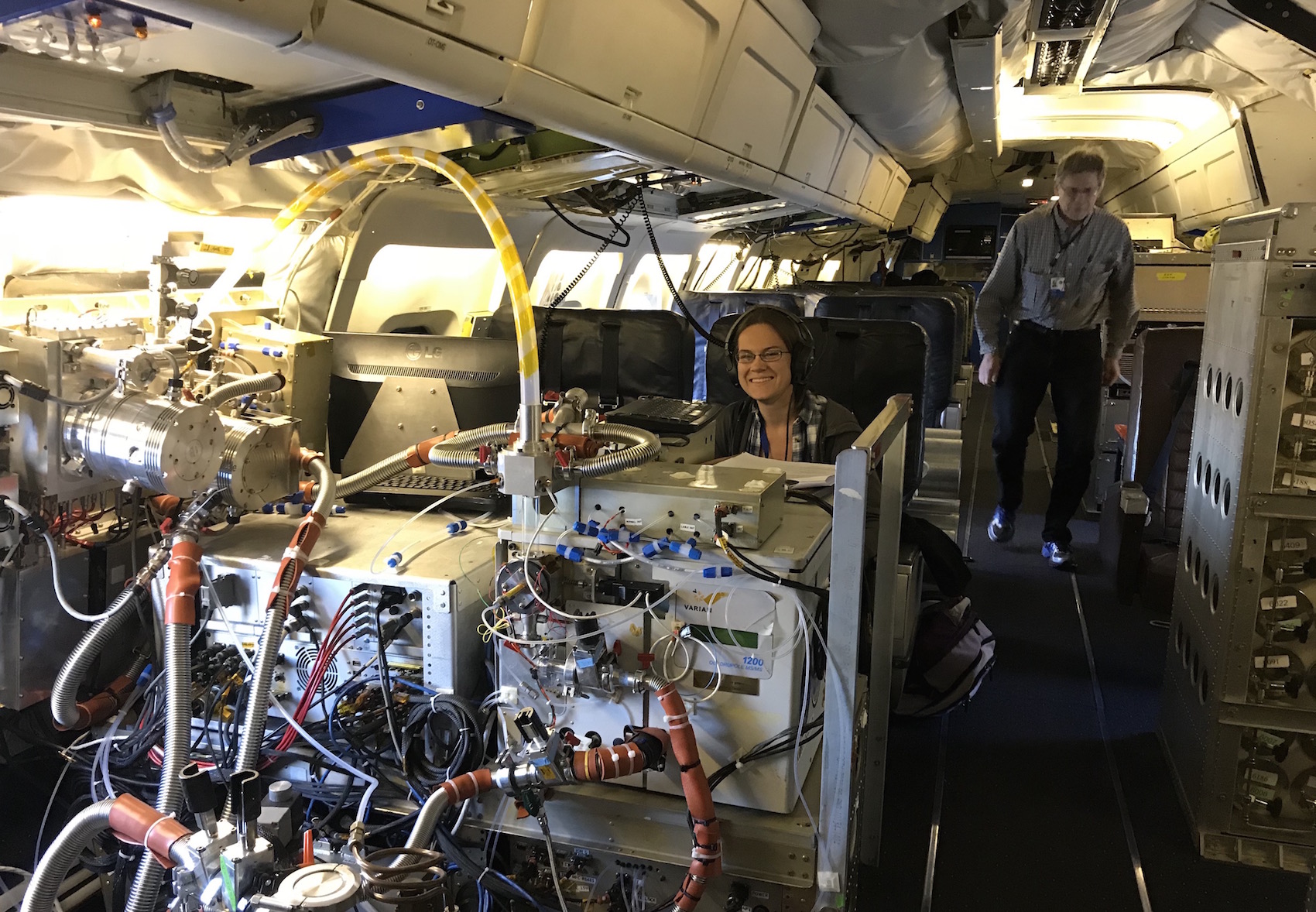

Because we were conducting a global exploration of the atmosphere, there were some pretty unusual logistics involved with ATom. Unlike most field studies, which have a single home base, we were island hopping to a new location every two or three days. Our stops include places as diverse as California, Alaska, Hawaii, Fiji, and New Zealand to survey over the Pacific, the southern tip of Chile for the midway point, and then Ascension Island, Brazil, Cabo Verde, the Azores, Greenland, and Maine to get the Atlantic side of things. We flew this pattern four times over the course of two years, each time consisting of 13 flights conducted in 26 days, to investigate how our results changed over different seasons. While we didn’t sleep on the plane, for those 26 days the DC-8 was effectively our home-away-from-home, complete with a microwave and an endless coffee pot. And several roommates: the plane housed 15 crewmembers, 30 scientists, and 25 instruments packed together in a space the size of a typical cross-country commercial aircraft. Needless to say, there wasn’t much room to maneuver on board, particularly when trying to tear something apart to fix a broken component.

The author sitting at her instrument on the DC-8

John Crounse

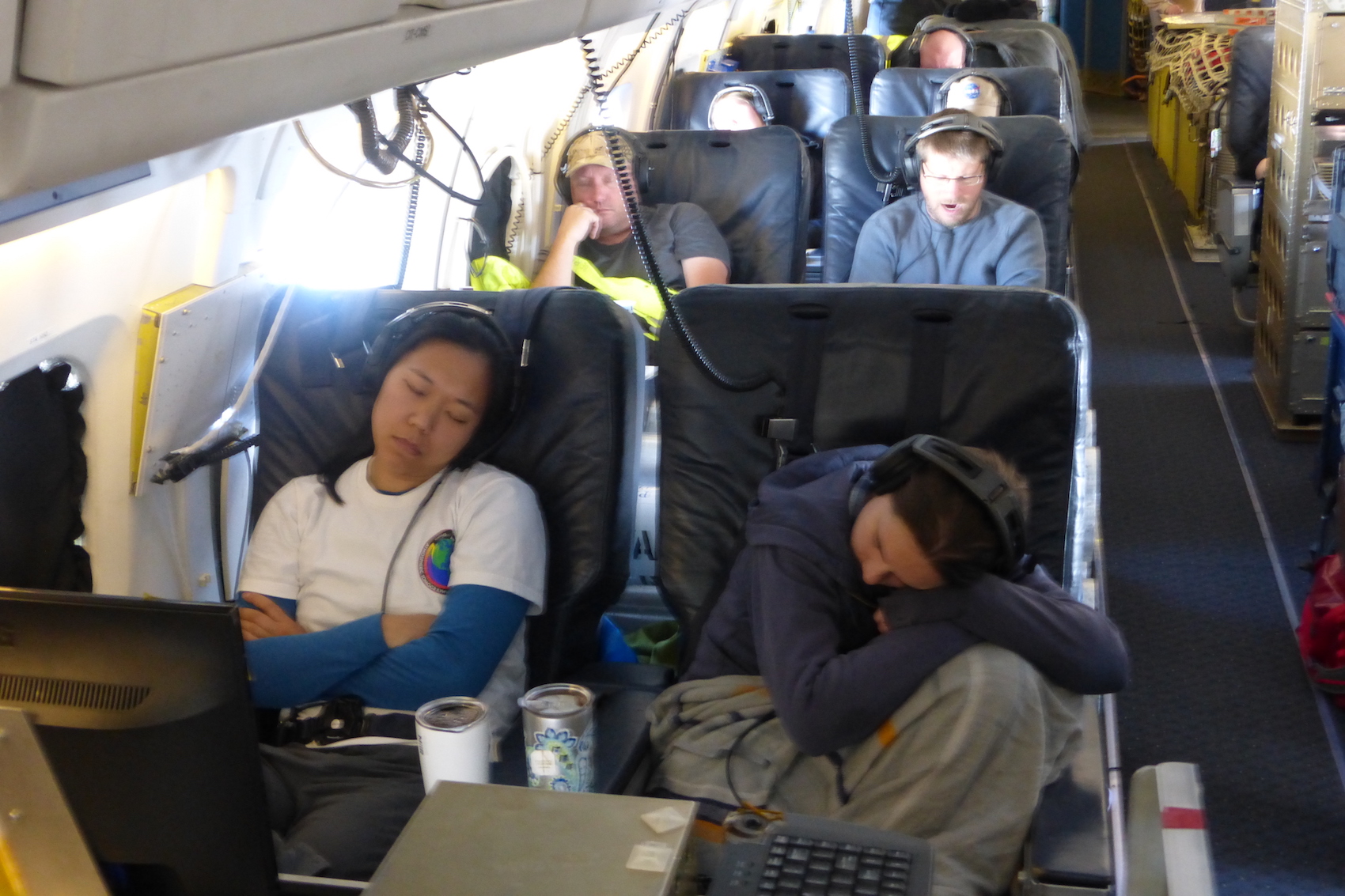

While flying on ATom, the instruments became the center of our attention. Much like a small child, they required constant attendance before they were ready to brave the outside world. On flight days, we arrived at the plane before 5 am and spent three hours warming up and calibrating our instrument while the crew busied themselves preparing the plane for that day’s mission. After takeoff, we spent the next 10 hours babysitting the instruments while we explored the atmosphere by conducting vertical profiles, slowly rising and dipping from 500 ft to 40,000 ft above sea level. If things were going well, I got to spend that time watching colorful lines of data wiggle across the screen and hear people chatter excitedly about them. At some point the droning of the plane and the constant time zone changes would induce a level of drowsiness that even coffee couldn’t dispel, and hoping that the instrument continued to behave, I’d find a semi-comfortable position to steal a much needed nap. The amount of work on non-flight days depended on the instrument’s crankiness level during the previous flight. A good day meant a few hours of maintenance and the chance to spend the afternoon sightseeing in a new location. A bad day meant 12 hours of frantically fixing whatever we could before the crew, per flight regulations, finally kicked us off the plane.

Some much needed rest during one of the long flights on ATom

Dave Tanner

And we know that at some point the instrument will have a bad day. As a lab-mate says, “instruments hate leaving their comfort zone even more than you do.” ATom very much takes instruments out of their comfort zone; they must tolerate everything between the punishing heat and humidity while sitting on the ground at the equator to the below-freezing temperatures of the high-altitude polar atmosphere. One of the toughest parts of being in the field is that you no longer have access to the luxuries of the lab: the near infinite time, the easily accessible materials, and the comfort of plenty of room to work in. Packing well becomes a necessity as you try to prepare for any situation you might find yourself in. Fortunately, traveling among a group of scientists with a shared goal builds a sense of camaraderie and everyone is usually willing to lend a hand in any way they can. Less fortunately, most instruments on the plane are unique and have parts that are highly specialized, so you are often left on the edge of the world with no manual, relying solely upon your own knowledge and the equipment you packed.

Which brings us back to that cold, windy day in Punta Arenas, Chile. By that point in the campaign we were exhausted and no longer knew what day or time it was, nor did we care. Our world had shrunk to contain only the 5-volt power supply that was failing our instrument. After trying and failing numerous times to resuscitate it, with time slipping away as we anxiously watched for signs the crew was going to force us off the plane, we finally resorted to something like open-heart surgery. We bypassed the failing supply altogether by cutting off the end of a completely new AC-to-5V-DC-converter we had bought that morning from a hole-in-the-wall electronics store in Chile and soldering the wiring to the computer in place of the old power supply.

The sense of relief and accomplishment we felt when the computer eventually flickered back to life was immense. Sitting back during the next day’s flight over Antarctica, I smiled as I got to relax for a moment and enjoy the unique view of the ice-strewn ocean below and data streaming across the screen in front of me.

Enjoying the view of Antarctica from the plane after the successful last-ditch effort to power the instrument’s computer

Hannah Allen

Learn more about ATom here