When you think of creativity, what comes to mind? Is it an image of a one-eared painter madly throwing paint on a canvas to translate their mind’s image into reality? Is it a poet or writer, her body rocking and rolling all night with lofty incantations, scribbling madly under the light of a single bare bulb? A man with wild hair lecturing ideas about the universe that seem so far-fetched they cannot possibly be true, until he produces the mathematical equations to prove it? A creative mind is not exclusive to those who study the arts—as you can tell from the examples given, creative thinking is integral in all possible occupations and situations. In science, solving the hardest problems often involves coming up with a new technology or a new approach using old techniques to work around the challenges.

But what exactly is creativity?

We all know of the classic dogma that the left brain is for analytics and logic, while the right brain is more emotional and creative. However, recent advances in neuroscience indicate that this simplistic view of the creative process is inaccurate. Scientists now understand that both sides of the brain must work in concert, making numerous connections and sending countless signals for the act of creativity to work.

Artistic rendering of a brain

Nicolas Antille, The Blue Brain Project

Recent progress in the technology of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines has led to in-depth brain scans during the activity of creation. A study by Roger Beaty’s cognitive neuroscience group at Penn State performed fMRI brain scans on 163 participants while doing a divergent thinking task—that is, a task that required participants to explore creative solutions to common problems. The participants were given a commonplace object and were given 12 seconds to come up with a creative application for that object. Creativity was defined as a new and useful application for these commonplace objects. For instance, if the object was a paperclip, an uninspired answer would be attaching papers together, while a creative answer may be using the paperclip as a needle.

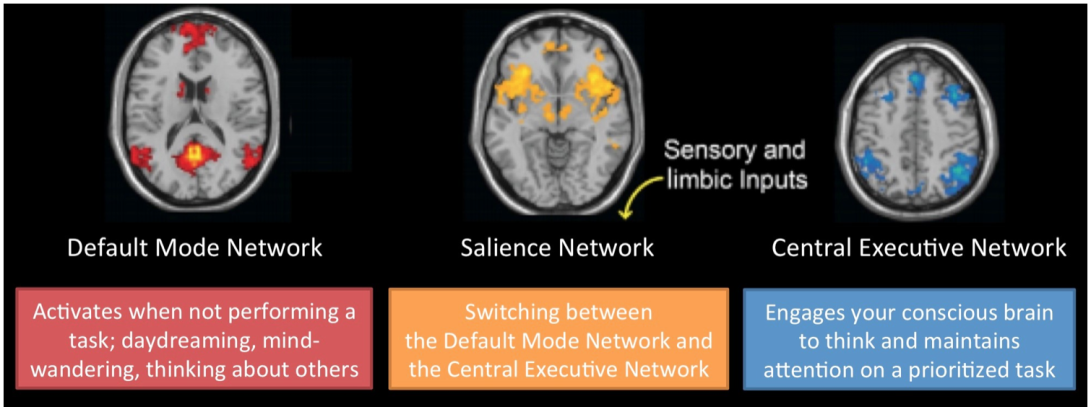

Analysis of the brain activity from these 163 patients revealed that highly creative thought was correlated with increased activity within three different networks in the brain previously found critical for this type of thinking. These networks are composed of interacting brain regions that are highly correlated with each other, and often fire at the same time for similar processes. The three networks that are specific to creativity are the Executive Attention Network (or Central Executive Network), the Imagination Network (also known as the Default Mode Network) and the Salience Network.

The Executive Attention Network is responsible for targeted attention and focus. This network involves communication between lateral (outer) regions of the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for decision making and complex behavior, and areas toward the back of the parietal lobe, which integrates spatial sensory information such as touch and navigation. As we all know, however, the human attention span can be incredibly short, and the Executive Attention Network often switches rapidly with another network, the Imagination Network.

The three networks of the brain that are associated with creativity; the Imagination (Default Mode), Salience and Executive Attention (Central Executive) networks. The networks function together to produce what we think of as creative thought.

Adapted from Bressler and Menon (2010)

The Imagination Network is integral in creative activities such as brainstorming and daydreaming. It is also responsible for social cognition, such as our ability to understand what someone else may be feeling, or how to react in a particular social situation. The Imagination Network involves communication within the prefrontal cortex, along with communication with various outer and inner regions of the parietal lobe. This network is sometimes viewed as the genesis of creative thought, as it is the network in control of performing mental simulations. However, it is the interaction of the spontaneity of the Imagination Network and the focus and sharpening tools of the Executive Attention Network that yield true creative thought as a final product. Interestingly, parts of both the Executive Attention Network and the Imagination Network occur within the prefrontal cortex indicating potential cross-talk between the two networks.

Finally, the Salience Network is in charge of monitoring the internal stream of consciousness, as well as external stimuli and events. This network makes the decision as to which information, internal or external, is most adept at solving the problem at hand, and is very important in switching between various brain networks. For example, the Salience Network is in charge of taking the massive amount of sensory information that you are being bombarded with constantly and choosing which sensations we should pay attention to (and which we should ignore).

As mentioned previously, creative thought relies not on just one of these networks, but in the constant switching of connections between the brainstorming capabilities of the Imagination Network and the decision-making and detail-oriented Executive Network. The Salience Network is in charge of monitoring which of these networks is most adept for the processing of ideas at the given moment and for switching to a different network when necessary. For example, when creating a new guitar solo, you would initially require increased activity in the Imagination Network in order to evoke emotional reactivity and sensory processing necessary to produce a novel musical motif. However, once you have the beginnings of the creative lick in your head, the Salience Network would switch you over to the Executive Attention Network so you could create a working memory of the otherwise transient melody and focus on nailing the music down into a memorable cadenza.

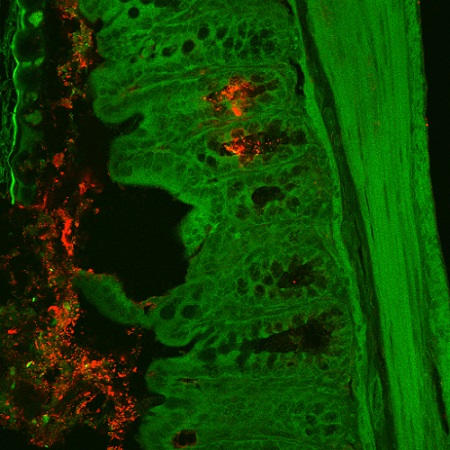

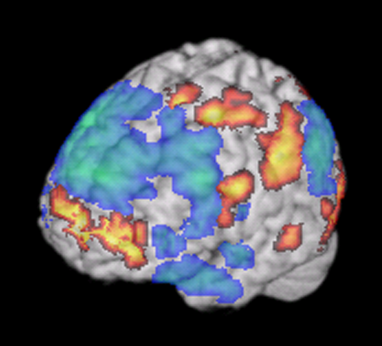

An example of brain activity during a freestyle jazz improvisational performance. Orange indicates areas of activation, and blue indicates areas of deactivation. The pattern seen here is associated with a switch from the Executive Network to the Imagination Network.

Charles Limb and Allen Braun

The connections between these three networks, and the speed at which they interact, are predictors of how creative a person will be. Individuals with more connections are more likely to think outside the box and think of new solutions and possibilities. Bealy’s study was able to use the models of network connectivity during creative thought explained above and use it to predict a person’s capacity to generate novel ideas by comparing the functional connectivity of their brain from fMRI data.

There is still a lot more to uncover about the brain and the network required for creativity. Our exploration of the brain during the process of creation is just beginning, as we continue to use fMRI scans to track brain activity during creative processes such as performing improvisational jazz or freestyle rapping. The playwright George Bernard Shaw once said, “Imagination is the beginning of creation. You imagine what you desire, you will what you imagine, and at last, you create what you will.” It is striking that the current model of the neuroscience behind creativity so closely follows these words, even 75 years after they were penned.