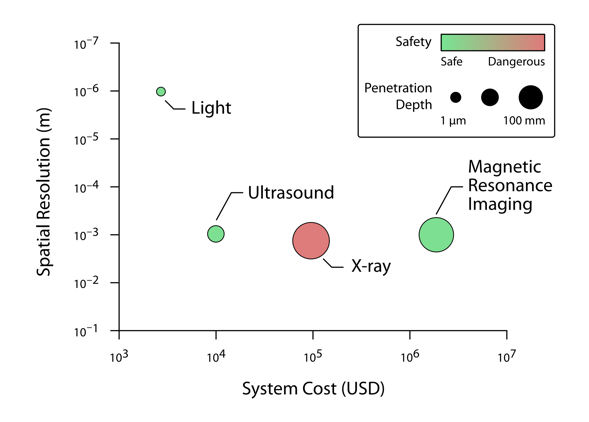

Have you ever wanted to see what you look like inside? The ability to see deep into biological tissue is critically important for medicine—imaging techniques such as X-ray, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are widely used for diagnoses. However, each of these techniques has its disadvantages: X-ray uses ionizing radiation, which is harmful to the body, ultrasound is limited in the types of structures in the body it can detect, and MRI requires large, expensive magnets. On the other hand, light is cheap, safe and can create high-resolution images.

There’s only one problem: most light-based techniques fail to work beyond depths of around 1 mm in biological tissue because tissue is opaque. This jives with our everyday experience, because you can’t see through your hand, right? As a result of this opacity, optical tools are normally limited to applications like microscopy where samples are very thin and we can get clear images. Does this mean that light is not useful for deeper imaging in biomedicine?

A comparison of common biomedical imaging technologies. Imaging technologies based on light, ultrasound, X-ray, and MRI have different strengths and weaknesses based on their spatial resolution, cost, safety, and penetration depth. Light is a particularly attractive method since it can support high resolutions and is safe cheap. However, conventional imaging technologies that use light have very shallow penetration depths.

Josh Brake

Why is tissue opaque?

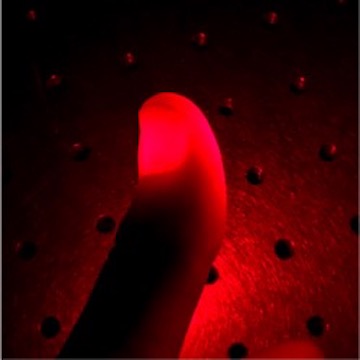

For anyone who has played around with a strong flashlight, what I said about the opacity of biological tissue thicker than 1 mm may sound suspect. If you put your finger on top of a bright light you’ll notice that your finger turns a reddish hue. (Go ahead and try it out with the flashlight on your phone if you have it handy). Obviously, the tissue isn’t totally opaque, since there is still some light that can travel through. So what’s going on here?

There are two main processes that cause light to be attenuated: absorption and scattering. Absorption occurs when a material extinguishes light by absorbing photons and converting them into a different form of energy, such as heat. An everyday example of photon absorption occurs when you are standing outside on a sunny day in a black t-shirt. The shirt absorbs many of the incoming photons from the sun, making it appear opaque and causing it to heat up as the sunlight is converted to heat.

On the other hand, scattering simply causes the photons to change direction. When enough photons are scattered, this can turn a beam of light into a diffuse haze. Think of what happens when you are driving with your car headlights on in a fog: as soon as the light hits the water droplets in the fog, it turns from a strong beam into a hazy glow. The property responsible for this phenomenon is called the refractive index, which relates the speed of light as it passes through through a substance, like water or air, to the way it passes through completely empty space. Since water and air have different refractive indices, the light changes direction as soon as it hits a water droplet, thus spreading out the intensity of the light.

The optically scattering nature of biological tissue. A red laser beam from the right illuminates the author’s thumb. Due to the low absorption of biological tissue in the visible wavelengths, the light penetrates through the tissue and illuminates the entire thumb. However, the strong scattering nature of the tissue causes the laser beam to diffuse within the tissue and leads to a glowing, hazy appearance.

Josh Brake

Let’s return to the example of biological tissue and the shining a flashlight through your finger. Just as fog causes light to scatter and diffuse, the components inside biological tissue have a variety of refractive indices, which causes light to scatter. Luckily, the absorption of biological tissue is relatively weak, about one hundred times weaker than the effects of scattering. This means that while the light is strongly scattered, the photons still exist within the medium and can carry information back to your detector.

So now we have a better idea of what’s going on inside the tissue. But even though the light isn’t absorbed, doesn’t the scattering still prevent us from seeing deep into biological tissue?

Reversing Time?

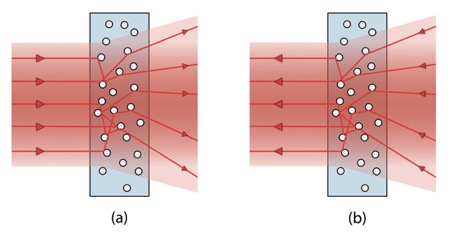

Imagine we could strap a GPS tracker to each photon and individually trace its trajectory as it scatters through the tissue. Then, once a photon had passed through the tissue, we could simply have it retrace its steps in the opposite direction to send it back to where it entered the tissue. This concept is called time-reversal and is a fundamental property of the way light, sound, and other types of waves propagate.

Using time-reversal to undo the scattering of a light beam. (a) A light beam strikes a scattering medium, which causes the individual photons to change direction. (b) By reversing the direction the photons are traveling and sending them back into the scattering medium from right to left, the scattering process can be undone and result in a recreation of the original beam exiting the left hand side of the scattering medium.

Josh Brake

Using time-reversal, the scattering nature of tissue can effectively be turned off, allowing us to to look through biological tissue. This overcomes one of the major limitations of current optical imaging technologies—limited penetration depth—and opens the door for optical technologies to be applied in new biomedical imaging contexts.

One application I’ve been working on as part of my Ph.D. research is using time-reversal techniques for deep tissue optical stimulation of neurons. An exciting development in neuroscience over the last decade is a technique called optogenetics, which makes neurons sensitive to light. In contrast with electrical stimulation using electrodes in the brain, optogenetics enables us to more precisely control the brain cells we are interested in studying; however, light scattering prevents us from looking as far inside the brain as we would like. To access neurons deeper below the surface of the brain, we have to use optical fibers inserted into the tissue to deliver the light. Obviously this is not ideal!

Using time-reversal techniques allows us to focus light several times deeper inside brain tissue than we could with conventional methods, controlling brain activity without the invasive insertion of optical fibers. While this technology is not ready to be implemented in your local hospital yet and is currently only used in the research laboratory setting, it is possible that in a decade or two these technologies might be a part of exciting new diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Until then, you can think about time-reversal when you pick up the nearest flashlight and show all your friends that they might be more transparent than they think.