Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

Every Friday, I run a Dungeons & Dragons adventure at my local game shop. It’s one of my favorite ways to meet people outside of Caltech. Armed with bags of dice in every color imaginable, I guide players through zany high-fantasy tales and lay out puzzles for our team of intrepid heroes to solve.

But tonight’s D&D session isn’t your standard lair-crawling, monster-slashing module. Tonight, I’m running an adventure that doubles as science outreach. I still have plenty of classic D&D hijinks planned, but as a battery chemist, I’ve put my own spin on the story. I’ve written different types of real-world batteries into the game mechanics, and I’ve plotted a tale that will show my players how those batteries work as they use a battery-powered device to defeat this week’s villain. As people start to join my table, introducing themselves or chatting about their characters, I’m excited to see how they’ll approach the science-themed adventure I’ve laid out.

The author's “Dungeons, Dragons, and Batteries” game setup, complete with multicolored dice.

Skyler Ware

My battery-based D&D module was developed with the assistance of the STEM Ambassador Program (STEMAP), an outreach training program that helps scientists design their own community engagement activities. I had a little experience leading community outreach, though mainly through programs developed by someone else. STEMAP taught me to design my own outreach program, and their approach surprised me in its difference from the work I’d done previously.

STEMAP prioritizes building trust between scientists and the community, instead of a strict focus on teaching science. Rather than reaching out to conventional places of learning like schools, libraries, or museums, STEMAP encouraged us to look for places where science outreach doesn’t usually happen, like game stores or tattoo parlors, among others. Looking beyond the obvious venues allowed us to reach people who don’t, or can’t, engage with science in those spaces. And instead of showing up with a demonstration already planned out or with activity kits already in hand, we spent time talking to leaders and representatives of the focal group—the group we wanted to work with—about the best way to present scientific material before we even began planning our program.

STEMAP's approach encourages science outreach in less conventional places, like tattoo parlors or breweries.

Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

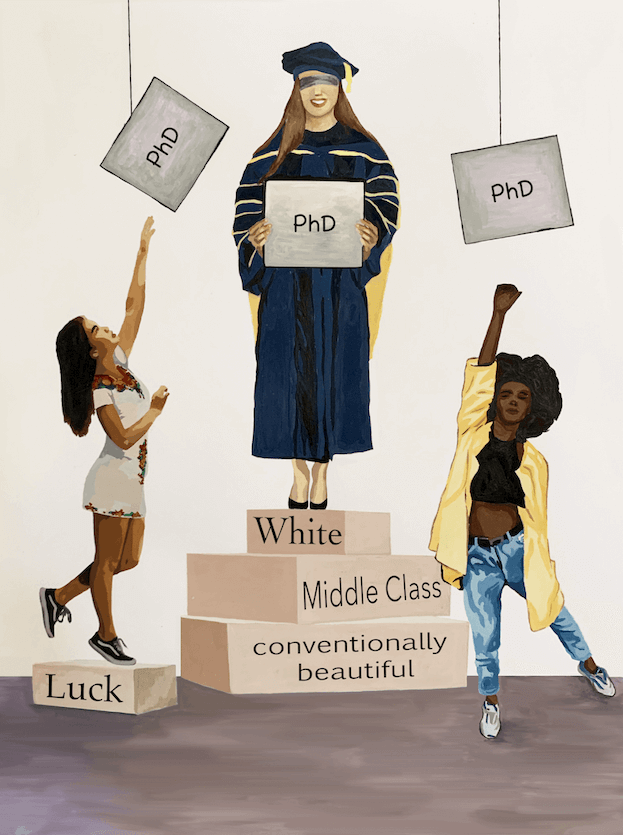

This relationship-centered model seems simple, but it fosters an empathic approach to outreach that seems to be lacking in the modern scientific community. Too often, scientists fall into the trap of the “deficit model”: the belief or assumption that skepticism of science stems from a lack of scientific understanding, and that we do outreach to teach science to people who lack scientific knowledge. But that approach devalues the sociocultural factors that influence attitudes toward science, ignores what people might already know about the topic from their own lived experiences, and erases the group’s agency in deciding how and why they want to learn more. The deficit model alienates people whose science knowledge draws from experiences outside of formal education, who have historically been undervalued by scientific institutions, or whose attitudes toward science stem from deeply held values and beliefs that are challenged by scientific advances. In contrast, a more empathic, value sharing approach increases public interest in science and improves scientists’ connections to their communities.

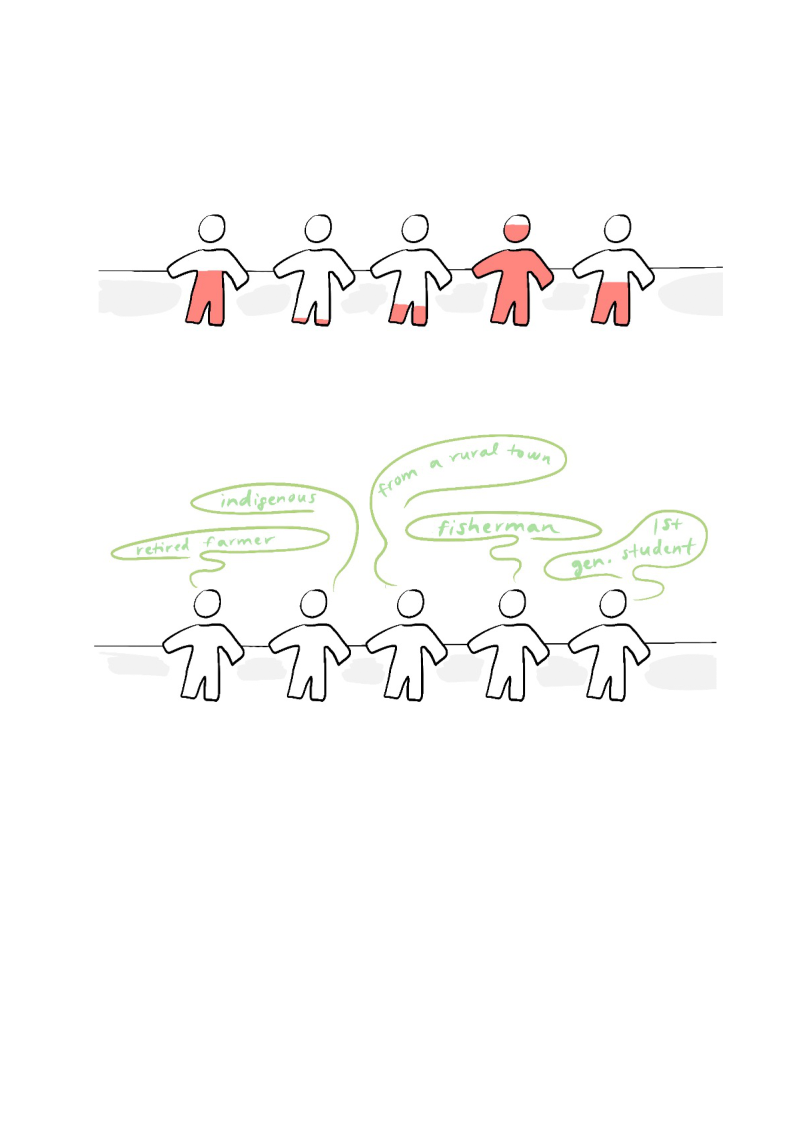

The deficit model sees scientific outreach as a didactic practice, providing scientific knowledge where it was previously lacking. The relationship-centered model recognizes and draws on the lived experiences and existing knowledge of community members.

So how can we, as scientists, build authentic and trustworthy relationships with the communities we want to reach? Below are a few considerations that we can implement at any stage of the engagement process.

Get to know your audience. When communicating our science, trainees are encouraged to “consider your audience,” usually to get us to think about our audience’s education level. Dig deeper. Consider your audience’s interests, the tools and resources they have (or need), and the knowledge or skills they might already have acquired outside the school system. Use those interests, tools, and knowledge to build common ground.

Talk to community leaders. Build your outreach and engagement programs in collaboration with people who already know your audience. Ask what the group wants to learn. Listen to, and learn from, how they already engage with science. Spend time in the space you’ll be occupying. Resist the urge to guess (or to assume you already know) what your audience cares about or how they want to engage with the material.

Be your full self. Engage with your own community, whether that community is built around shared identities, interests, or values. That shared connection can be as deep or as frivolous as you want it to be, but bonding over something important to both you and your focal group builds trust and invites the public to see you as more than just your lab coat. Building that trust is just as worthy and important of a goal as sharing the science, and it will open doors to more effective and long-lasting relationships with our communities.

I encountered a powerful example of these principles in action at a conference in the summer of 2022. I met a researcher from South Africa who was working with rural and tribal groups to find more climate-friendly alternatives to coal mining. Her efforts weren’t focused on educating those groups on climate change though; as she explained, they already knew a lot about the effects of climate change on agriculture from their own lived experiences. They understood the science of climate change through a different lens, and they knew that closing coal mines would help fight both climate change and mining-related illness. But closing the mines would destroy the economies of their mining towns. Rather than hammering home the negative impacts of coal mining on the environment, her work focused on building trust and open conversations with the residents of those towns to ensure that alternatives to the coal mines would meet their economic and public health needs.

These principles can be applied just as easily in less politically charged situations, like classroom outreach or my battery D&D adventure. Though the stakes are much lower, there are clear parallels in how our focal groups respond when given the freedom and agency to direct their own engagement with a topic. When we approach outreach with empathy and openness, we build stronger, more trustworthy relationships with the communities we want to reach.

As our party of heroes defeats their last imaginary foe, I look out across the table at the smiling faces of a team that were strangers to each other, and to me, not three hours before. Even if they don’t remember a single thing about batteries, I’ve taken the first steps towards building an outreach relationship based on trust and mutual interest. I’ve shown that I’m more than just a scientist, and that I see them as more than just people who don’t know about batteries. Building trust through shared values might not be a typical focus during outreach, but I’m hopeful that by prioritizing those relationships, we can grow lasting, authentic, and impactful educational partnerships.