Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

I hold that policy is our chief danger at the present moment.

—What the Black Man Wants, Frederick Douglass, 1865

In September of 2013, I took the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) General Test. Equivalent to the undergraduate SAT, this standardized test is one of the requirements of graduate school applications in many universities in the US, including Caltech. I scored a 152 out of 170 (50th percentile) in both verbal and quantitative reasoning, and a 3.5 out of 6.0 (40th percentile) in analytical writing. I was demoralized. Until recently, Caltech’s admissions office had stated that, “on average, admitted students score in the top 90th percentile.”

While finishing my undergraduate degree in Mexico, I was also scrambling to put together applications for graduate schools with only the guidance of online blogs and university websites, helping my non-English speaking professors write me letters of recommendation, contributing to research on campus, and organizing an international science conference with distinguished scientists and 400 attendees from Mexico and Latin America.

A few weeks after taking my test, I received an email: “Our records indicate that you took a GRE® test at least 30 days ago. If you are planning to retake the test, you are eligible to do so.” I was not enthusiastic about the additional investment of money, time, and effort.

I had time to take the GRE once more, just in time to submit my graduate school applications. Over the following weeks I memorized one thousand English words—most of which I don’t remember now—and practiced with a pirated GRE guide. The month went by, and I took the test again. This time, I scored 164 for verbal reasoning (93rd percentile), 160 for quantitative reasoning (76th percentile), and 4.5 for analytical writing (78th percentile). Better, although still not the 90th percentile.

In Mexico, a country where the average monthly income is less than 1,000 USD, I grew up with privilege. My increased GRE score reflected that very privilege: having the time and money to pay and prepare for the test; being able to pay for a second chance; and overcoming the belief that my original score was an unfixable measure of my ability to succeed. This challenge was magnified by the false impression that only geniuses—and not just any motivated, persevering, and curious individual—should have a chance to enter the top universities of the world.

Men are so constituted that they derive their conviction of their own possibilities largely by the estimate formed of them by others.

—What the Black Man Wants, Frederick Douglass, 1865

Among other things, that second chance to take the GRE made the difference. I was thrilled to get accepted into a PhD program in biology at Caltech.

As a graduate student in 2016, I had the opportunity to teach a week-long science workshop for college students in Mexico as part of Clubes de Ciencia. My students were selected from a pool of highly motivated applicants, eager to become scientists. I tried to convey to them what, in my experience, had been the best path from college student to scientist in a developing country. I told my GRE story, and what I had discovered back then: you will get the score that you prepare for.

Towards the end of my workshop, I discussed the path to graduate school in the US, including the costs of applying to graduate school. First there was the GRE—$205. Then comes an English test (TOEFL), an additional $180. The Caltech application fee was $100. Finally, transcript shipping and translations cost an additional $60. A total of $545 for a single graduate school application.

In a country where $545 represents half the average monthly income, it did not occur to me to put my words in the context of my privilege of having enough time and money to invest in applying. I also neglected to bring up the GRE preparation material and extra courses that can cost hundreds of dollars, whose quality I could not even personally vouch for.

To my surprise, two years later, one of my students from that workshop reached out for advice in graduate school applications. He was one of the four Mexican students I had the opportunity to closely advise on their applications.

On top of working in a lab conducting full-time research, doing the very job that would prove they could succeed in graduate school, these four students also needed to find the time to prepare for the GRE. They had to find the money to pay for the test and transportation to a test site, which were only in major cities often far from them. They had to stress over whether or not they were prepared to take the GRE, dreading trial by a supposedly objective score that would determine their intellectual value.

For each of these students, whose talent for research was on par with any student I’ve met at Caltech, their experiences led them to not apply to schools requiring the GRE. The existence of curated lists with programs without a GRE requirement suggests this effect is pervasive.

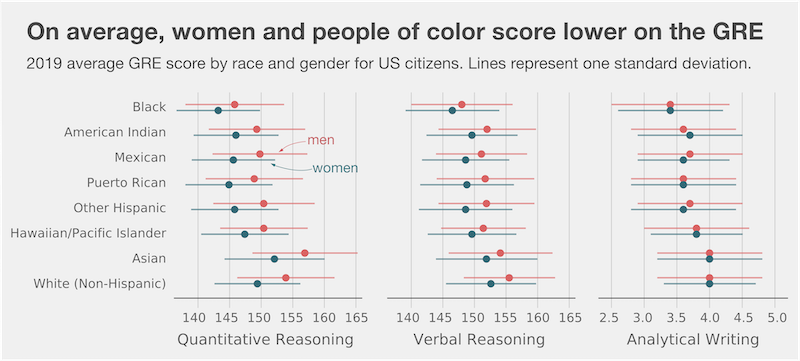

The problems with the GRE go beyond individual stress and finances; on average, non-Asian people of color score lower than Asian and white people on the GRE, and women consistently score lower than men.

On average, people of color score lower than white people on the GRE, and that women consistently score lower than men.

Porfirio Quintero for Caltech Letters, Data from ETS

ETS, the company that sells GRE tests, explains the correlation above as follows: “The achievement gap in education refers to the different levels of academic performance of students from a variety of racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. The lack of access to high-quality education in a child’s early years has a deep and enduring impact on development and academic achievement.” I could not find scientific support for this statement on ETS’s website, so I assume they claim this “achievement gap” and “impact on development” is measured by their own tests.

One may wonder, is this test useful for selecting the best graduate students? Researchers have repeatedly failed to find a correlation between an applicant’s GRE score and any informative metric of graduate school success, such as the number of first-author publications, likelihood of graduation, or time to PhD defense1,2,3,4. My own experience is an example of how privilege alone can substantially improve a GRE score, and another manifestation of the correlation between race, gender and privilege. Of course, this phenomenon is not breaking news.

After completing my PhD at Caltech, conducting research on par with the work of my talented peers, and proving to myself that I can succeed in academia, I see more clearly now that the only thing a GRE score correlates with is privilege. It is now with frustration and conflict that I see an institution, where we pride ourselves on being leaders in science and engineering, in analyzing and interpreting data, continuing to justify the use of a test that specifically keeps out less privileged talent, despite overwhelming evidence against its usefulness.

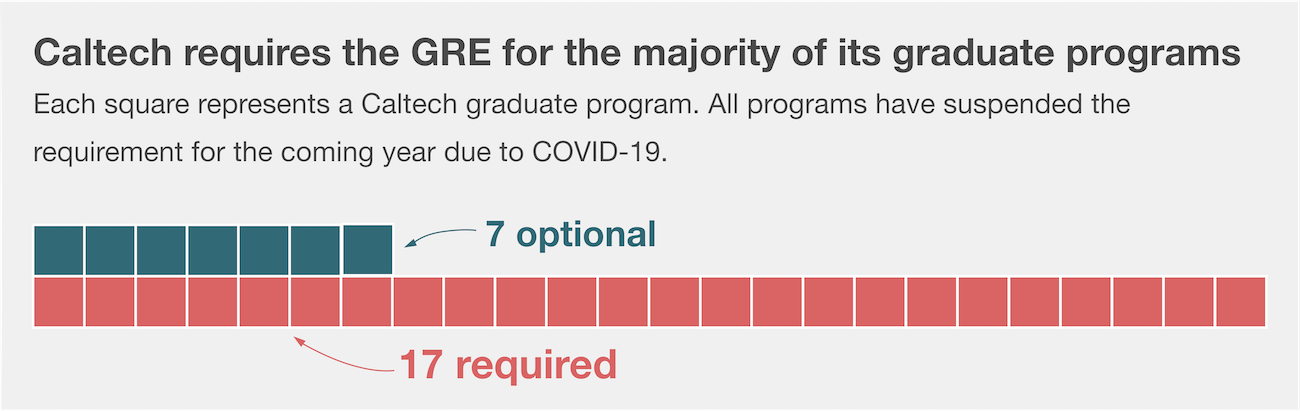

Plot showing GRE requirements for Caltech programs.

Porfirio Quintero for Caltech Letters, Data from Caltech and personal communications.

From my experience in graduate school applications, advising other applicants, and talking to Caltech faculty with experience on admissions committees, I’ve seen three ways in which the GRE negatively impacts less privileged talent in our applicant pool: women and people of color.

-

The first impact is that it outright prevents students with less time and money from applying. The GRE works as a class filter, invisible to all of Caltech’s admissions committees.

-

The second impact is demoralization. The GRE requirement discourages applicants from believing in themselves in spite of their creative efforts to even get to the position where they could apply.

-

The third impact occurs when faculty in the admissions committees look at a GRE score that is low by Caltech standards and see not the perseverance and ingenuity needed to overcome the lack of privilege, but exactly the opposite. Faculty see students with less promise to succeed.

It is utterly disappointing to come to the realization the GRE is so ubiquitous at Caltech when it is evidently a racist, misogynistic, and classist policy. As an alumnus, proud to have completed my PhD in this institution, I believe we can and must do better.

Only 6% of Caltech’s graduate students identify as underrepresented minorities, only 31% as women, and there are just 11 Black graduate students on campus. Why do we lack women and people of color? How do we address this lack of diversity? I acknowledge these are challenging questions.

In July 2020, the Black Scientists and Engineers of Caltech group proposed ways to move forward, including dropping standardized tests in admission. Caltech departments have suspended the GRE due to COVID-19. Permanently dropping the GRE is an embarrassingly obvious step on our path to becoming an antiracist institution, one small manifestation of enacting the recipe below:

Admit racial inequity is a problem of bad policy, not bad people. Identify racial inequity in all its intersections and manifestations. Investigate and uncover the racist policies causing racial inequity. Invent or find antiracist policy that can eliminate racial inequity. Figure out who or what group has the power to institute antiracist policy.

—How to Be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi, 2019

Cover image: DHS via Wikipedia

References

1: Levesque, Emily M., et al. “Physics GRE Scores of Prize Postdoctoral Fellows in Astronomy.” ArXiv.org, 10 Dec. 2015, arxiv.org/abs/1512.03709.

2: Moneta-Koehler, Liane, et al. “The Limitations of the GRE in Predicting Success in Biomedical Graduate School.” PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0166742.

3: Petersen, Sandra L., et al. “Multi-Institutional Study of GRE Scores as Predictors of STEM PhD Degree Completion: GRE Gets a Low Mark.” PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0206570.

4: Miller, Casey W., et al. “Typical Physics Ph.D. Admissions Criteria Limit Access to Underrepresented Groups but Fail to Predict Doctoral Completion.” Science Advances, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1 Jan. 2019, advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/1/eaat7550.full.