Out in the night sky, there are giants lurking. You wouldn’t know it unless you spent a while looking out at the stars with a pair of binoculars on a dark night. Even then, you would only see them if you knew what to look for: faint, golden smudges that seem to disappear when you focus on them. Those fleeting smudges are galaxies—the massive hulks out beyond all the stars we see with the naked eye, each as large and containing as many stars as our own Milky Way.

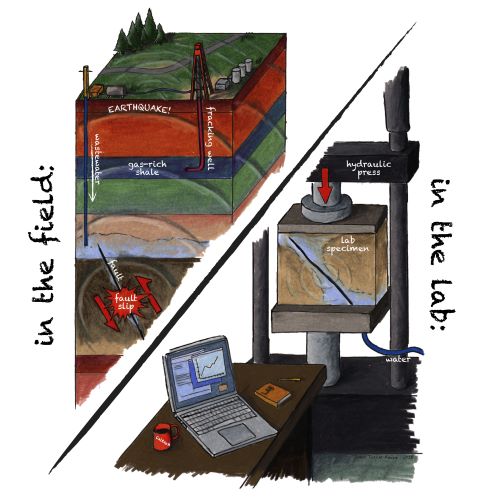

The Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) as seen from the Hubble Space Telescope

Hubble Archive (NASA+ESA), public domain

These things are giant by every measure. Even the Sun, orbiting the center of the galaxy at over 200 km/s (around 450,000 mph), takes more than 250 million years to go around the Milky Way once. That means dinosaurs were walking around only a quarter of an orbit ago. In addition to all those stars, spiral galaxies have vast reserves of dust and gas. This material, having fallen into the galaxies over the history of the Universe, provides the matter that forms new stars. And these massive, rotating collections of dust, gas, and stars floating around the universe really only have one job: turning that dust and gas into even more stars. Yet, galaxies are terrible at it.

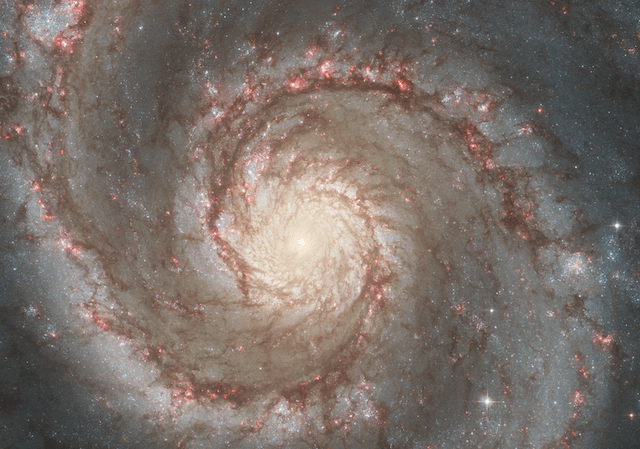

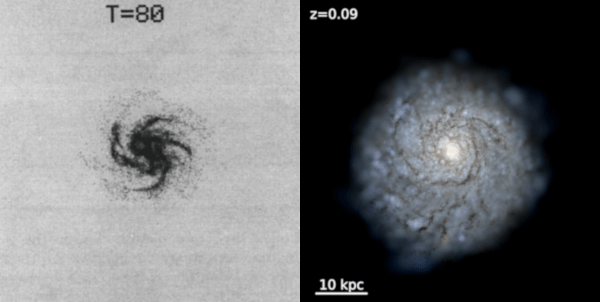

To realize galaxies are terrible at their one and only job, we first have to calculate how quickly they should be producing new stars. First, we estimate the amount of star-forming material available in each galaxy, which is its gas and dust reservoir. These cold, dense materials don’t shine brightly as visible light. However, they do emit infrared and radio waves. These waves can be measured by huge radio dishes in “quiet” areas far from cell towers and radio stations, and by telescopes up above the Earth’s atmosphere. Using these measurements of the faint signals emitted from the gas, we can work out how much gas there is in these galaxies, and how dense it is. From that, and our knowledge of gravity, we can infer how long it should take for all that gas to collapse on itself in free-fall. In a simple universe where gravity alone determines how quickly stars form, this would be how long it takes for a galaxy to turn all that gas into stars.

The Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) as seen in its radio emission from CO molecules. Looking at the light from galaxies at different wavelengths tells us a lot about what is going on in galaxies, and where stars are forming. In this radio image, we can see lots of dense gas in the spiral arms of M51.

Schinnerer et al. 2013

Alas, the universe is not so simple, but thanks to that, I still have a job.

You see, we can also estimate the true rate of star formation by measuring the ultraviolet light given off by the brightest and biggest young stars. These stars have comparatively short lifetimes and give off much more ultraviolet light than ‘normal’ stars like our own. Their brief and abundant light emanate from the star-forming regions in galaxies. So we can tell how large these regions are and how many stars are in them, by the extent and intensity of their light. And it turns out that the rate at which we see galaxies turning their gas into stars, estimated by measuring this ultraviolet light, is fifty times slower than it should be, given our measurements of the star-forming material available in galaxies and its gravitational free-fall time.1 Therefore, something must get in the way of all that gas collapsing down to stars as quickly as it ought to. My job as a graduate student is to figure out what that something is.

Astronomy is an observational rather than experimental science, so to understand the paradoxical inefficiency of star formation, we have to watch a galaxy age and produce new stars. But galaxies are slow movers, and in a human lifetime, they effectively don’t change at all. We’re stuck with a single snapshot in time of the galaxies in the universe that we can see with our telescopes. Any guess at how galaxies change and grow in time is like comparing pictures of a young woman and an old man to understand how people age. Not only are we missing images of the intermediate steps, but some of the differences between the two images are unrelated to age.

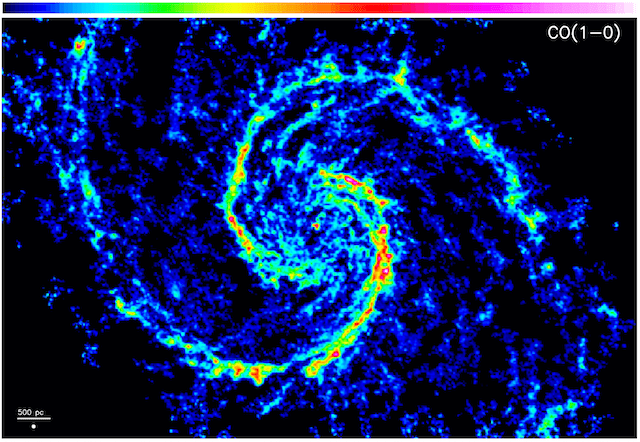

Luckily, these giant star factories do not just live out there in space, spinning excruciatingly slowly in the dark. They also live on my laptop. I have spent many an afternoon sitting in my favorite coffee shop, Copa Vida in Old Town Pasadena, building artificial galaxies in simulations. To run these simulations from my laptop, I remotely command supercomputers, which are effectively many thousands of computers all wired up to work on the same calculations together. In my calculations, I let galaxies live out the history of the universe, and, with each calculation, I slowly learn how to build realistic-looking galaxies.

Galaxy simulations have advanced considerably since the 1990s. A simulated galaxy from 1994 (left) compared to one from today (right). We have learned a lot about how to build galaxies and what goes on inside of them through simulations like these.

Left: Mihos & Hernquist 1994, Right: Matt Orr, Visualization of m12b from FIRE-2 simulations, Hopkins et al. 2018.

To build a galaxy from scratch, we start our simulations with the conditions of the Universe just after the Big Bang: a soup of hydrogen and helium gas. No stars, no galaxies. We then add gravity into our simulations, which pulls everything in the universe together, as well as the minimal amount of additional physics that we think we need to make galaxies. Once we have our starting point and the physics that will act on it, we run the clock forward and watch these forces at play. In this way, simulations bring astrophysics into the realm of the experimental sciences. They allow us to watch how galaxies grow up through cosmic time under different physical conditions, and to figure out which conditions match our observations of real galaxies.

With these simulations on local laptops, we have paradoxically unlocked the secrets of the galaxies lurking distantly in deep space. For example, knowing how the stars in galaxies come to be helps us understand where our Sun and all the other planets in the Milky Way come from. We can also estimate how many other Earths might be orbiting Sun-like stars, potentially harboring unknown life. We might even predict the future, since knowing what happens when galaxies collide may reveal the outcome of the Milky Way colliding with our nearest cosmic neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy.

You might be wondering how we learn so much about the universe using simulations that don’t include all the physics we know. Why not throw the kitchen sink at the problem of galaxies, and include every possible physical mechanism we can think of? First, in the same way that you can build a car cheaply and quickly without windows or a radio, we can easily construct a useful galaxy model with only the essential components. Second, we can always add things to our car, such as power steering or anti-lock brakes, to see how they change the experience of driving. Slowing adding extra parts, like winds from young stars, new rules for star formation, or different gas physics, lets us isolate the effect of each bit of physics on galaxy formation.

Incrementally expanding the code also makes it easier to track down the bugs we have put in the code by accident. This simple and streamlined code is less likely to grind to a halt or take forever to run on the supercomputer. As a result, in the 90 minutes of free parking in Old Pasadena, a computer running a modern Milky Way-like galaxy simulation on 120 CPUs can simulate 100 million years of that galaxy’s recent history. This is enough time to watch half a turn of the real Milky Way, and for a few generations of the most massive stars to be born, live, and die.

In the last couple of years, with the help of my simulations, I have learned a lot about the effects of young stars on star formation in our galaxy simulations. The biggest and brightest of those young stars in a galaxy don’t live for very long, cosmically speaking. Unlike our venerable Sun that has been burning steadily for 4.5 billion years of its nearly 10 billion year lifetime, these stars exist for a few million years at most. These bright, short-lived stars end their lives spectacularly in star-shattering supernova explosions, whose light outshines whole galaxies for a few days. However, the explosions of these bright, massive stars can inhibit the formation of new stars around them by stirring up all the gas. These intermittent interruptions to the star formation process explain why galaxies produce stars less efficiently than expected. Star formation in galaxies is a balance of two processes. While gravity is pulling dust and gas together into clumps that form new stars, these not-quite-stars-yet clumps of gas can be struck by one of these supernova explosions and easily shredded.2

Young stars destroy the clouds that they form out of. The bright, hot light from the biggest of them quickly begins to shred the envelopes of dust and gas around them, and the supernova explosions that follow blow out the rest of the cloud.

Accounting for the effects of these explosions and the other effects of young massive stars, like the winds that they blow into their surroundings and their ionizing light, we have found that galaxies like our own Milky Way are producing stars nearly as efficiently as is possible. Making stars fifty times slower than we naively expected isn’t all that bad. Galaxies might be terrible at their one job, but they’re doing their best.

References

1: Kennicutt, R. and Evans N. Ann. Rev. of Astron. & Astrophys., 2012.

2: Orr, M. E. et al. Mon. Not. of the Royal Astron. Soc., 2018.