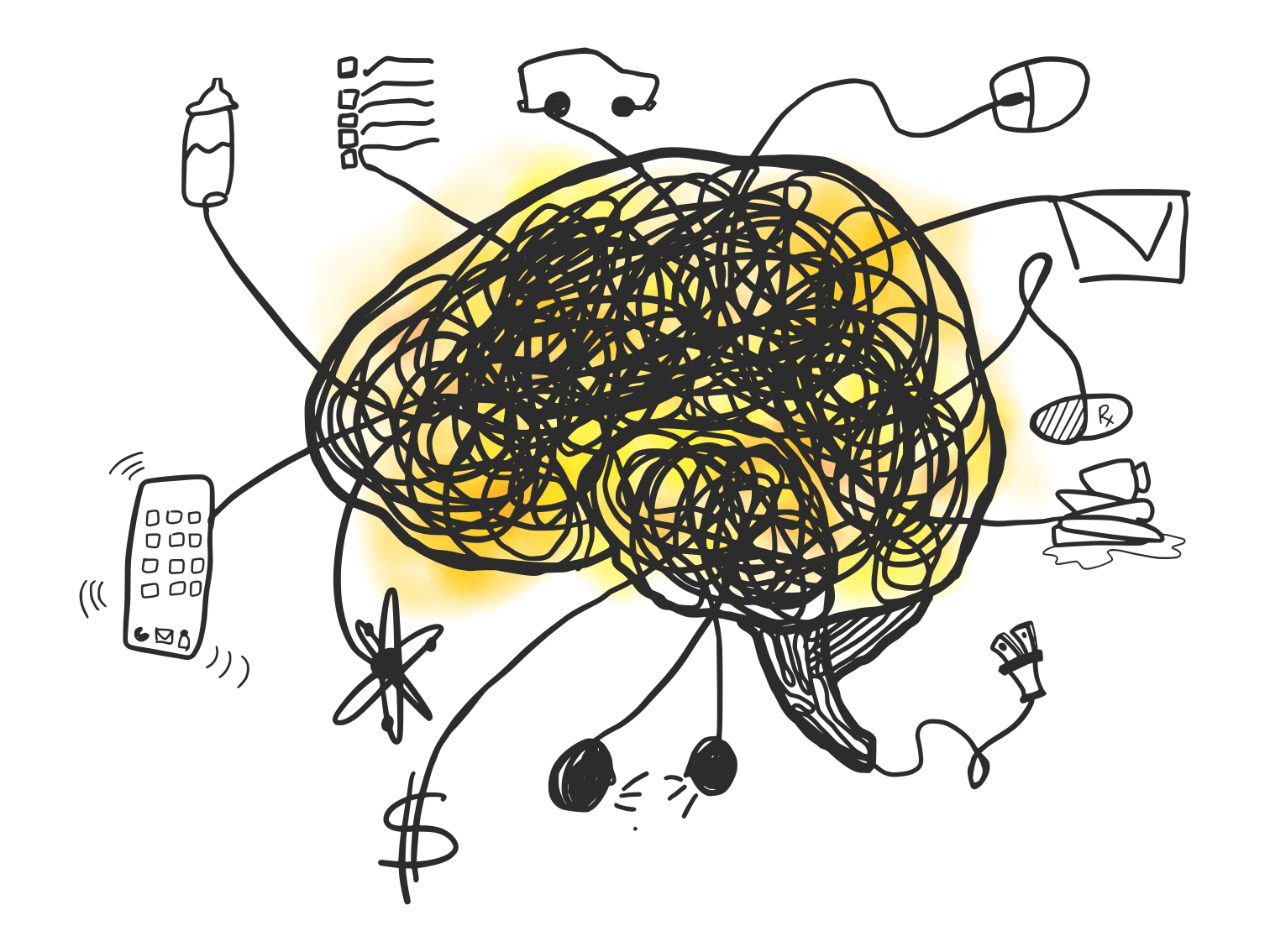

Illustration by Olivia Harper Wilkins for Caltech Letters

Content note: this article contains discussion of suicide, depression, anxiety, and general mental illness.

If you or someone you know is considering harming themselves, please visit the Suicide Prevention Lifeline website or call 1-800-273-TALK (8255). If the concern is imminent, please call 911 if off-campus or institute security at (626) 395-5000 if on-campus.

Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

On April 1, 2019, I woke up right on time at 7:30 a.m., but I lay in bed for a half hour more, afraid to get up. It felt like my body was playing an April Fool’s prank on me by waking up without an alarm at 7:30 in the morning. For the last few months, I hadn’t been able to get out of bed until at least 9:30 or 10:00, at which time I would be urged out from under the covers, aching and exhausted, by my husband.

Staying in bed until 9:30 a.m. might not sound much like sleeping in; however, my then-three-year-old—who is adamant about a 6:30 or 7:00 wake-up time most days—begged to differ. My body would feel weak, and I would feel unable to face the day. These weren’t symptoms of a physical ailment; they were manifestations of my depression and anxiety.

I have lived with depression for almost as long as I can remember, with my first memory of overwhelming hopelessness going back to when I was five or six years old. My depression is always lurking, and every few years it comes out in full force. Despite having fought against it many times throughout my life, it evolves and continues to wreak havoc on my mental health just when I think I have it under control. Although I should know better, my go-to tactic for taking care of my mental health has been to just ignore it altogether. There is also a lot of stigma around mental health, making it even harder to face it head-on. Fortunately, I have many support structures in my life to make me feel empowered to share my experiences and talk about the larger problem of mental health in graduate school, in the hopes of providing resources and a sense of community to those who are struggling.

Feeling depressed or anxious at times is a normal part of life. However, when these feelings last for many days or weeks, they may be part of a mental disorder that disrupts your sleep, energy levels, or baseline mood. They can also contribute to a sense of worthlessness or persistent guilt that you’re not doing enough or are a burden to those around you. It is common for graduate students like myself to feel inadequate (hello, imposter syndrome) when they are faced with failure or the perception that they don’t know enough. However, depression and anxiety can magnify these feelings such that they become crippling.

The author with her partner Alex and son Günther in Cologne, Germany, during winter break in her first year of grad school (2016).

Olivia Harper Wilkins

While I had long struggled with depression, I learned that I also struggled with anxiety when I was enrolled in a particularly difficult class in my second year of undergrad. Several weeks into the semester, during my hour-long drive home, I started to notice a tingling numbness in my arms and tightness in my chest: symptoms, I thought, of a heart attack. These symptoms only got worse by the end of the semester, and I decided I need to see a doctor. My drive to my hometown family doctor, however, took a detour to the nearest hospital when I suddenly had a stabbing sensation in my chest. I thought I was going to die.

When I arrived at the emergency room, I explained my symptoms through a shaking voice. “You’re just having anxiety.” The tone around the word “just” made me feel so little, so weak. I heard “It’s just anxiety,” at least five more times during my time at the hospital.

My experiences with depression and anxiety continued and worsened in graduate school. As a new graduate student at Caltech, I again felt the crippling anxiety that manifested as tightness in my chest, shortness of breath, and creeping panic. It was in response to the graduate-level version of the course that had sent me to the hospital four years before. My second year was miserable: I moved apartments, dealt with financial stresses, and traveled extensively for work. A friend likened this to the pain of 1,000 papercuts—on their own, annoying but manageable; all together, overwhelming and numbingly painful. The effects on my well-being manifested themselves in a number of ways: being constantly on the verge of tears, sleeping too much or too little such that I was dozing off at work, having nightmares that made sleep insufferable, isolating myself from others, and having panic attacks whenever I thought about presenting my work during what would otherwise be laid-back meetings with my research group. I considered therapy a few times, but how could I make time for that? Instead, I buried my anxiety deeper and deeper.

In my third year at Caltech, acknowledging the difficulty in recognizing my own crises as well as the weakness often (wrongly) associated with getting help, I decided to attend a crisis awareness and suicide prevention course. Instead of feeling empowered, I was transported back to age fifteen, to a situation in which I stayed up all night helping a suicidal friend through a crisis. I had felt an overwhelming sense of relief when I saw my friend at school the next morning and he told me he had dumped the bag of pills into the garbage can. Yet the latent guilt of not telling an adult at the time, despite the positive outcome, ended up triggering my panic disorder. What if…? I don’t remember the rest of the training. I was physically there the whole time, but my mind was trapped in this guilt-ridden memory.

The accumulation of my recent struggles and the triggering of my past trauma resulted in a relapse into a seemingly endless depressive episode. My depression evolved into a roller coaster of lethargy one day and being in a manic state the next. I became tired of fighting to survive, and I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to survive much longer. It felt like my depression and anxiety were slowly killing me. For a while, I was plagued by the occasional but still too-frequent passive suicidal ideation, but suicide has never been an option because I had promised my mom when I was younger that I would tell her if I was ever suicidal, and I couldn’t bring myself to worry her more than she already does. While I felt I was a burden, I clung to any shred of rationale that I wasn’t one. A friend told me that there were therapists I could email to set up an initial appointment so I could avoid having to make an anxiety-inducing phone call. I sent an email and started seeing a therapist the next week. Around the same time, my dad talked me into seeing a psychiatrist about starting medication, something that a classmate in high school had convinced me was a sign of weakness.

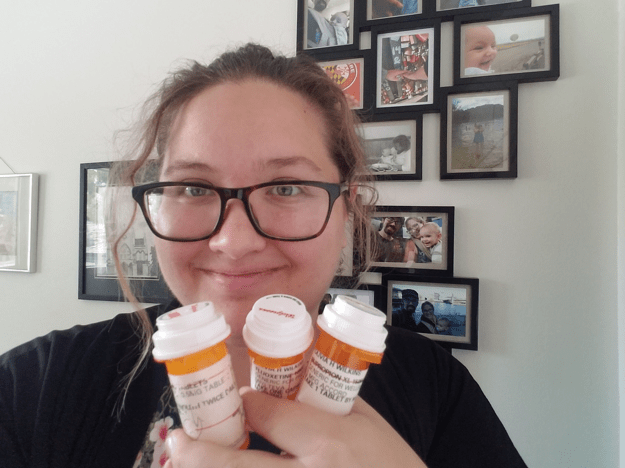

The author holding the bottles of her psychiatrist-prescribed medications. Fluoxetine (generic for Prozac, taken daily) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) used to treat depression and panic attacks. Bupropion (generic for Wellbutrin, taken daily) is used as an add-on medication to treat major depressive disorder to supplement first-line SSRI antidepressants that cause fatigue or have an incomplete response. Alprazolam (generic for Xanax, taken as needed) is used to treat anxiety and panic disorders.

Olivia Harper Wilkins

A combination of therapy and medication has turned this roller coaster into a kiddie ride most days, but the depression and anxiety are still there, sometimes taking me for an unexpected spin. At best, my depressive relapses leave me feeling numb and empty, like a shell left abandoned by the ocean; at worst, I feel trapped in that very shell, screaming into the void. Work-life balance has become a balance between guilt for not working enough and guilt for not giving enough time to my family and my own self-care.

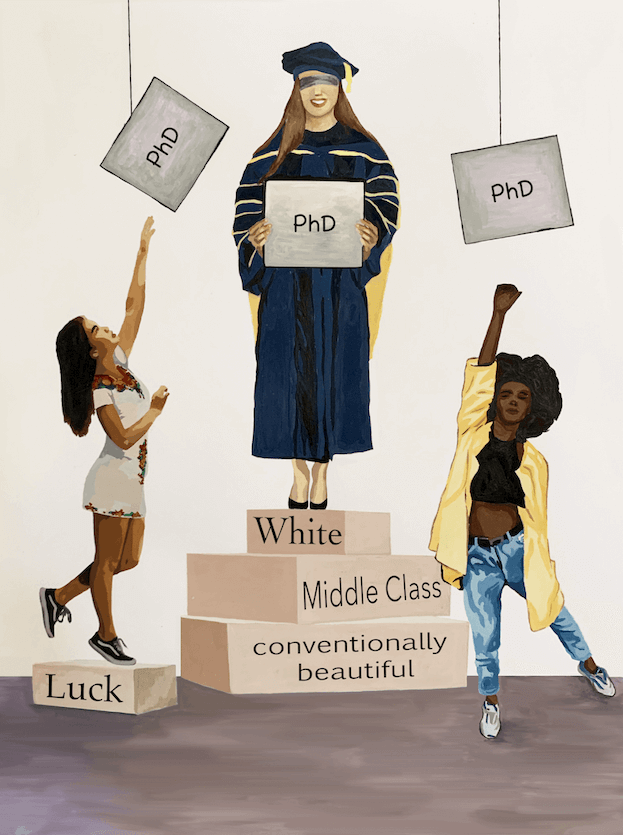

All the while, the notion that mental health isn’t that big of a problem has lingered, isolating me from peers who are facing similar struggles. During my second year of grad school, at a meeting in which both faculty and students were present, a faculty member expressed their perception that only about 5-10% of grad students struggle with depression or anxiety. The accompanying silence from their colleagues gave credence to the concern that this opinion is not rare among faculty.

Contrary to those beliefs, a study published in Nature Biotechnology in 2018 found that depression and anxiety are moderate-to-severe for about 40% of all graduate students, who experience these mental health struggles at a rate more than six times that of the general population. For transgender and gender-nonconforming students, this rate is even higher at 55% and 57%, respectively.

One perspective offered was that faculty advisors cannot know about the prevalence of mental health issues if students do not make them aware of it, which suggests that we should be more open about them. However, a friend of mine whose advisor called mental health issues a “perceived barrier” to research would advise the opposite. I trust my advisor to have my best interests at heart, but even so, telling them that I missed an entire week of research because my new antidepressants were taking a toll on my immune system was terrifying.

I share some of my experiences in this letter because while statistics are important in showing prevalence, they fail to show the tangible impact that mental health actually has on a student, their ability to maintain work-life balance (the above study shows trends that suggest better work-life balance yields better mental health outcomes), and their productivity as researchers. While universities ideally care about mental health for the sake of student well-being, at a minimum they should be concerned about the fact that mental health has been shown to impact student productivity.

I also share these experiences to help remove some of the stigma around mental health. My least favorite compliment is “I don’t know how you do it all,” because while I give the impression of having everything together on the surface, I often feel inadequate and struggle to cope with taking care of my own mental health. I am a Ph.D. candidate who has written numerous successful proposals, has taught almost every term since starting grad school, is involved in several committees on campus, creates and sells artwork, is writing an astrochemistry book, and is raising a small child, all with major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. These types of struggles often make you feel incompetent or incapable of being successful in graduate school, but they don’t make you incompetent or incapable. Talking about mental health and how to best provide support for those working with depression, anxiety, or other struggles is imperative for the well-being of our students. I hope that sharing my experiences will help others who are struggling know they are not alone and feel that they have a voice to talk about their concerns.

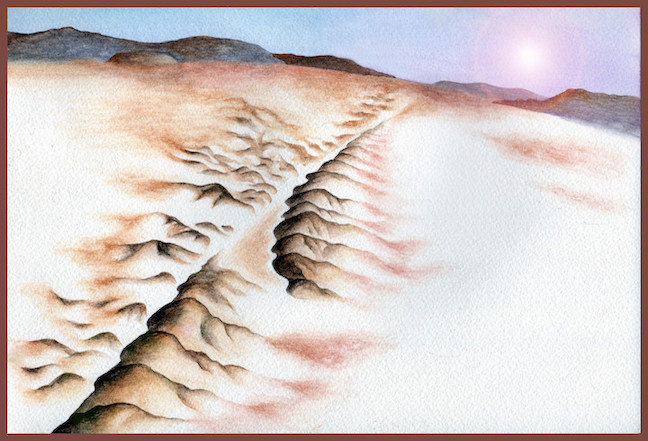

The author near the top of the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) in West Virginia, one of her favorite places in the world and the site of one of the instruments she has used in her astrochemistry research.

Olivia Harper Wilkins

There are other measures that we can take to continue to evolve support systems for graduate students, however. One tactic is to lay out a risk management approach in which stressors and stress outcomes can be mapped and monitored to assess general risk factors, like fluctuations in the job market, that affect all students, as well as risk factors that are specific to certain populations, such as students of color, LGBTQ+ students, and student-parents. In the chemistry program, we are developing a resource tree to be handed out during orientation and posted online and in labs. This tree will consider a number of ways in which students might need support and provide a cohesive guide to help students navigate the overwhelming number of resources on the Caltech website.

Mental health concerns can be isolating, and with the stigma surrounding mental illness, asking for help isn’t as easy as saying, “I need help.” Even asking “How is everything else going?” can help those suffering open up. Yes, graduate school is hard. It is challenging. If we want to keep it from overwhelming many of our students, we have to actively combat risks to mental health and student well-being. In our research, we are expected to assess risks and consider our assumptions before conducting an experiment or running a simulation. As scientists, we are trained to draw conclusions and take action based on data. With the growing data pointing to a mental health crisis among graduate students, why should the culture around mental health in grad school be subject to less scrutiny?

Resources

- On our campus and beyond, there are already some excellent resources available. Even if you are a student on a different campus, your institution might offer similar services; if not, I encourage you to start conversations to improve access to these services at your institution.

- In cases of emergency or imminent concern of suicide on Caltech’s campus, institute security can be reached at (626) 395-5000. If off-campus, please call 911.

- If you or someone you know is considering harming themselves or is in crisis, please visit the Suicide Prevention Lifeline website or call 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You can also get in touch with the Crises Text Line by texting HOME to 741741. If the concern is imminent, please call 911 for people in the U.S.

- The Student Counseling Services on campus offers goal-directed individual psychotherapy, as well as a range of workshops, support groups, and specialized group therapy, all at no cost. Appointments can be made by phone at (626) 395-8331 or online by sending a secure message through the Student Health Portal. Students can also consult with Occupational Therapy Services for concerns such as stress management or difficulty sleeping.

- There are a number of providers in the community that accept Caltech’s student health insurance that are available for open-ended or longer-term therapy. For community providers at the time of publication, 25 sessions are provided at no cost to students per year, and additional sessions require a $15 copay.

- Telephone crisis consultation with a counselor from Student Counseling Services is available after hours on weekdays, weekends, and holidays by calling (626) 395-8331 and pressing “2” when prompted.

- Students with mental health conditions that have a detrimental impact on their success can register with Caltech Accessibility Services for Students (CASS) and request academic accommodations.

- If you are concerned for someone else’s well-being on campus, and your concern is non-urgent, you can refer them to the CARE Team, a multidisciplinary group of Caltech professionals who helps connect students with resources and support.

- Caltech students are also invited to join the mental health community email list for information about casual get-togethers centered on community building among those interested in learning about mental health or who are struggling themselves.