It’s 1:00 a.m. and my Uber is winding its way home along a twisting freeway through the heart of Los Angeles. My driver seems in a talkative mood.

“So, what do you do?” he says.

I shake my head to clear the fog after a long evening.

“I’m a seismologist,” I respond, “I study earthquakes.”

“Earthquakes?” he says. “So can you tell me when the Big One is coming?”

The Big One. He’s talking about the massive earthquake that California is “overdue” for. Whenever I tell people what I do, this is the one burning question they have. Knowing when the Big One is coming feels like it could give us some control over our lives—lives every Angeleno spends on the unpredictable and uncontrollable ground that lurks beneath our feet.

California lies on the boundary between two giant tectonic plates. These blocks of the Earth’s crust are on the move, sliding about the same speed as your fingernails grow. But, along the 800-mile long San Andreas Fault where they meet, friction causes the plates to get stuck. As they try to slide past each other, the stuck plates bend, storing up energy like a coiled spring. When the pressure becomes too great, the fault slips; the plates move rapidly, violently shaking the ground.

The San Andreas Fault runs from the Salton Sea in the south to well north of San Francisco. Each part of it produces big earthquakes, causing the ground to slip tens of feet, every one to two centuries on average. When the last Big One hit Northern California, in 1906, it reduced San Francisco to rubble. Meanwhile, the southern end of the fault hasn’t ruptured in roughly three hundred years.

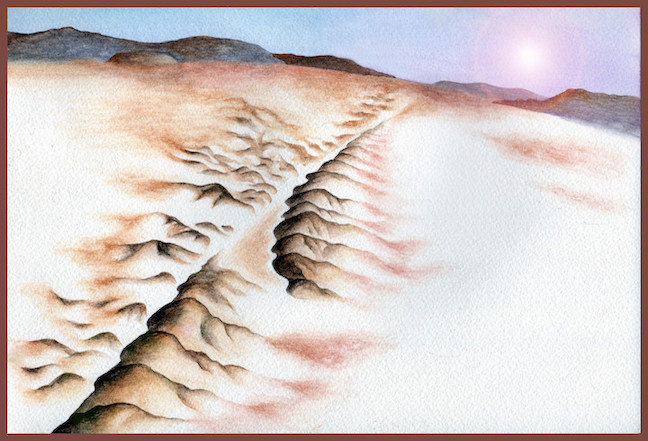

The San Andreas Fault at the Carrizo Plain, central California.

Illustration by Usha Lingappa for Caltech Letters

I study earthquakes, using supercomputers to simulate an event like the Big One. From the safety of my desk, I create ruptures that break a digital version of the San Andreas Fault to explore how the earthquakes start and what makes them stop. But even when I try to tame earthquakes in my computer, they’re still unruly beasts: fascinating, terrifying, and full of surprises. Centuries of studying the Earth has taught us that earthquakes are as inevitable as they are unpredictable. We don’t know when, but we do know the next Big One is coming.

“I’m sorry to disappoint,” I say to my driver, “but they’re random. We can’t predict them. Although we know it’s not a question of if, but when.”

Perhaps it’s the thought of the next earthquake, or perhaps the winding of the freeway, but I start to feel nauseous. My fingers make for the window switch to let in some slightly fresher air. Despite the late hour, my driver wants to know more. “That sounds pretty scary! What’s going to happen?” he says.

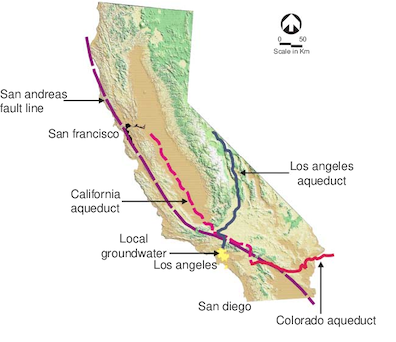

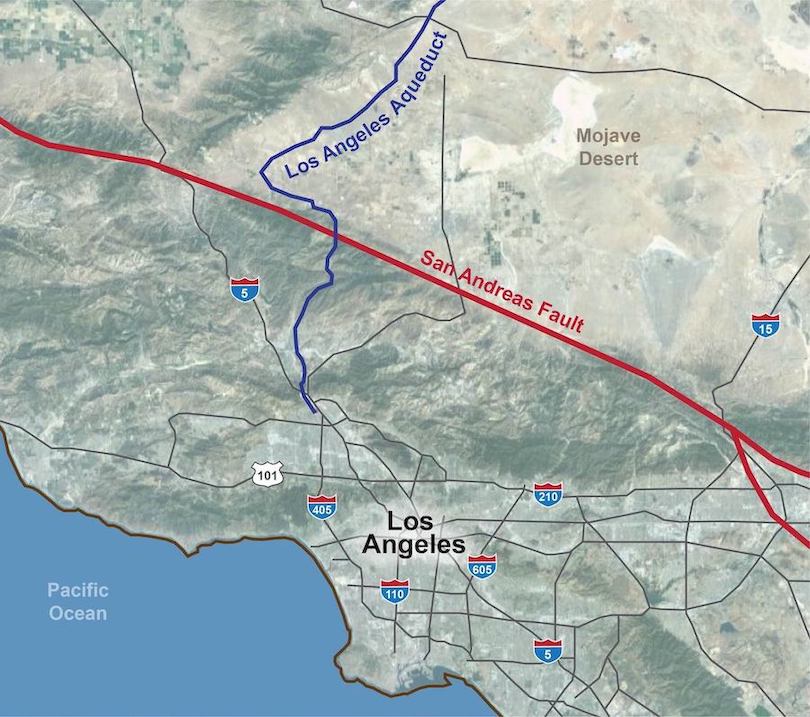

My driver’s question pushes my mind’s eye high above the ground, giving me a view of the whole of Southern California. The San Andreas Fault is a slice through the landscape, separating the San Gabriel Mountains from the Mojave desert. Crossing this scar in the ground is a thin vein that carries the blue lifeblood of our desert city: the Los Angeles Aqueduct, bringing us water from the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. This aqueduct, and others that also cross the fault, are the source of over 70% of the city’s water. One big slip of the San Andreas severs the city’s lifelines.

This map shows the three aqueducts that supply over 70% of LA’s water, all of which cross the San Andreas Fault. An earthquake on the San Andreas could sever these aqueducts.

I imagine the Big One starting, miles underground. The fault breaks, and once broken it starts to slip, one side sliding relative to the other at several feet per second. As it moves, the San Andreas sends out seismic waves in all directions, shaking the ground and everything on top of it. In a matter of seconds, the fault slides 20 feet.

The consequences are immediate. LA loses access to more than 70% of its water as seismic waves rupture gas mains and bring down power lines, sparking thousands of fires. Roads are broken, and cell towers overloaded. At the end of it all, the potential destruction to our city is immense: hundreds of billions of dollars in damage, families fleeing their ruined homes, and two thousand lives lost. The U.S. hasn’t seen an earthquake this bad in over 100 years.

Vital roads, pipelines and aqueducts cross the San Andreas Fault just north of Los Angeles.

Adapted for Caltech Letters by Usha Lingappa

Such a bleak future seems unreal to the human mind, when we can turn on our tap and have clean water, and I can hail a ride on my phone within minutes.

My car hits a bump, bringing me out of my head and crashing back into my seat. For a moment, I catch the driver’s concerned eyes in the rear-view mirror; he’s still waiting to hear what the Big One will do.

I hesitate for a second, trying to order my thoughts. Even though I study earthquakes, my scientific work has given me only a tiny piece of a puzzle that’s immeasurably complex, ranging from geophysics to infrastructure safety to disaster planning. We know where the big faults are, and the kinds of earthquakes they’ve caused before, but we don’t know how close to breaking they are now. We know how to make buildings safer, but we don’t know which buildings will suffer the strongest shaking. Here and now, all I can do is translate a tangled web of knowns and unknowns into the clearest possible answer. But we need an answer that’s not just a tale of destruction, leaving us powerless in the face of disaster. Instead, we need to tell the story of the progress that we’ve made and the steps we, as individuals and as a society, can still take to get ready for The Big One.

“There will be an earthquake, and it will hit us hard” I say, “but it’s what we do right now that determines just how bad that earthquake will be.” I recite the age-old words of earthquake safety: purchase supplies; have an emergency plan for meeting with loved ones; drop, cover, and hold on when the shaking starts. But I also tell him just how far we’ve come: a network of seismic sensors now watching the fault 24 hours a day, ready to send out precious seconds of warning when the Big One starts. The better mapping of dangerous faults, and the strengthening of buildings and pipelines.

Science won’t let us predict every random geological event, but it can teach us how to understand and prepare for those events. The catastrophe that I imagined is only one possible path; as a society, we can avert disaster. Preparation lets us tame the fear that uncertainty creates in our minds, and tame the threat that earthquakes pose to our lives. Generations of research mean that we’ve never been more prepared for earthquakes.

As our ride nears its end, I realize I’ve forgotten something, perhaps the most important thing we can do to get ready. Being prepared isn’t just a question of medical supplies and bottled water. “We need to get to know our neighbors.” I say. “Who lives nearby, who might need help after the quake. We can recover if we work together.”

I thank my driver as I step out into the cool night air.

A few weeks later, I find myself in a bar in Palm Springs. As I sit down, a woman next to me greets me and asks: “So, what do you do?”

If you’d like to find out more about how you can get ready for earthquakes, visit earthquakecountry.org

Note: This story was originally written before the 2020 pandemic. An earlier version was delivered at a live storytelling event at Caltech.