Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

As an incoming freshman in 2016, I received my first orange, Caltech-branded T-shirt during orientation. In cheerful comic sans, it proclaimed “Study, Eat, Coffee, All-Nighter, Repeat.” The facilitators waxed poetic about how we would bond spending long nights studying under the bright fluorescent lights of the library, running problem sets over to their drop boxes at 3 a.m. together, and enjoying the beautiful sunrises before finally going to sleep. The next four years were a whirlwind as I desperately tried to stay on top of my assignments, and it was only in the year after I graduated that I realized the extent to which I was burnt out by my time at Caltech. I realized the habits of overwork I developed as a student were working to my detriment outside of college. As it turns out, I wasn’t alone.

The "Study, Eat, Coffee, All-Nighter, Repeat" T-shirt the author received during freshman orientation.

Jadzia Livingston

In preparing for this article, I interviewed several recent alumni from various majors, houses, and extracurricular groups at Caltech. They all described experiencing burnout, an occupational condition characterized by exhaustion, lack of passion, and reduced productivity due to chronic workplace stress. Everyone felt it; we all agreed that overworking students makes them dislike what they are doing and makes them less effective at doing it. Each interview underscored an unfortunate truth: the Caltech undergraduate experience is structured in a way that puts students at a high risk of burnout and encourages bad work habits that will serve them poorly as they enter the workforce.

Every graduate I talked to remembered struggling to find time for everything. If their life was in perfect order, if every moment was scheduled, showers and meals were carefully timed, and leisure activities were used as a chance to do some of the easier work, only then was it possible to get all of the coursework done. There wasn’t a margin for error. There was never a moment to take for yourself, to think about what you were learning and what it all meant. There was always another set to do, another experiment to run, another recitation to go to. If something went wrong, if you got sick or injured, your whole life tumbled out of control.

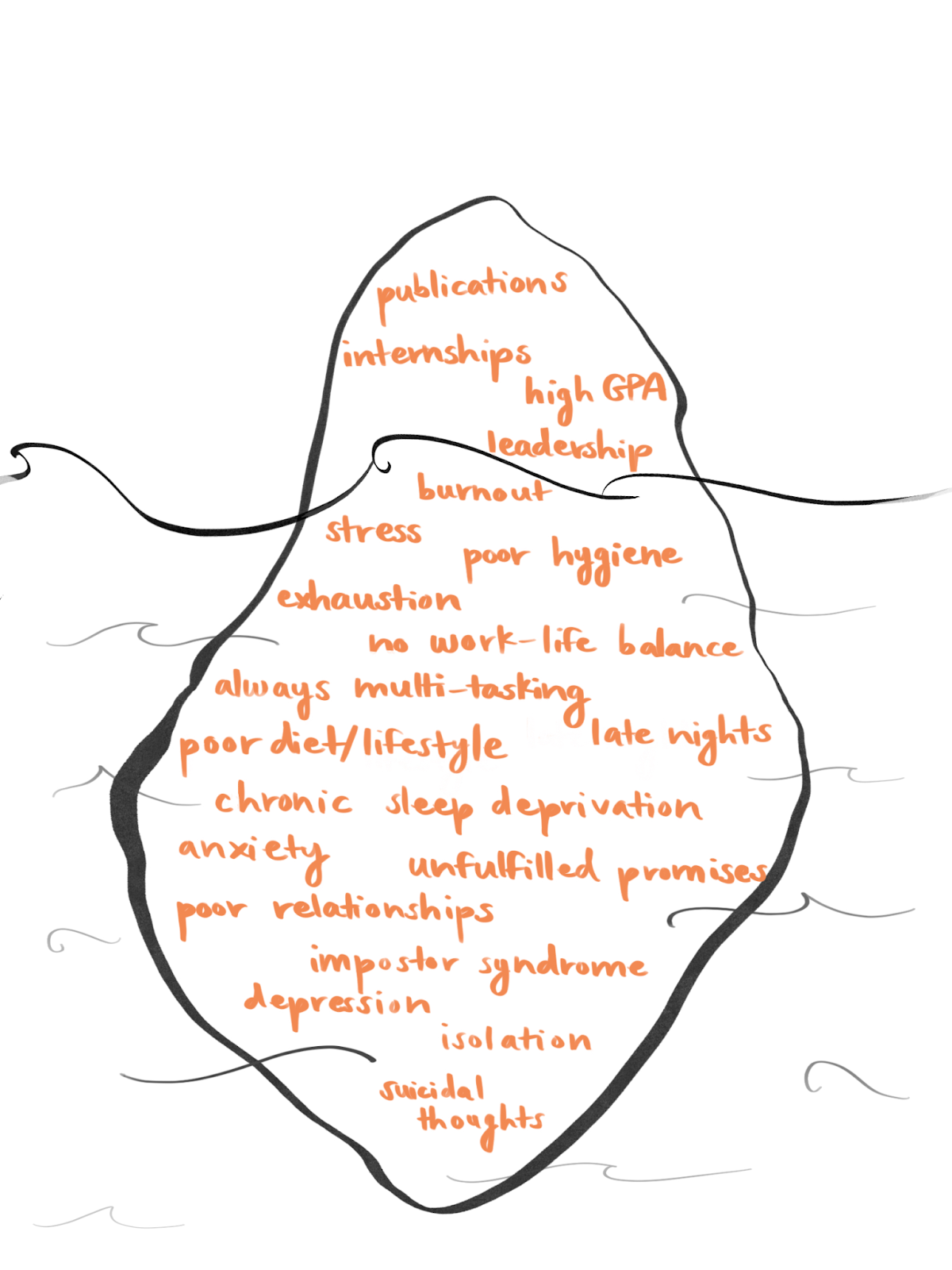

The appearance of undergraduate success often masks unhealthy habits and feelings of stress and burnout.

Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

I thought I flourished in that environment, having deadlines that pressured me to succeed in a short time. If every moment was carefully structured, then my productivity must have been maximized. If I spent every spare moment learning, then I must have learned a lot. To an outside observer, I was successful — I led two clubs, did publishable research, and kept a high GPA — but under the surface I was always exhausted, never slept enough, and felt like things were about to fall apart.

Many alumni I spoke to expressed concern that the students at Caltech were chronically sleep deprived. Some alumni worried that students aren’t aware of the negative effects of poor sleep habits, including reduced attention span, difficulties with memory formation and critical thinking, and increased depressive symptoms. Others worried that students—unaware of the consequences of poor sleep—were not putting in effort to fix their sleep schedules. Even though I knew the cost of sleep deprivation during my time at Caltech, I was still unable to maintain a healthy sleep schedule while also fulfilling my academic duties. The students I spoke to who did manage to cut enough time out of their work schedule to sleep often had to give up research, networking, teaching, or extracurriculars and deal with unbearable stress to make up the time “lost” to sleep. They didn’t feel they had the opportunities afforded to students who gave up sleep to get everything done.

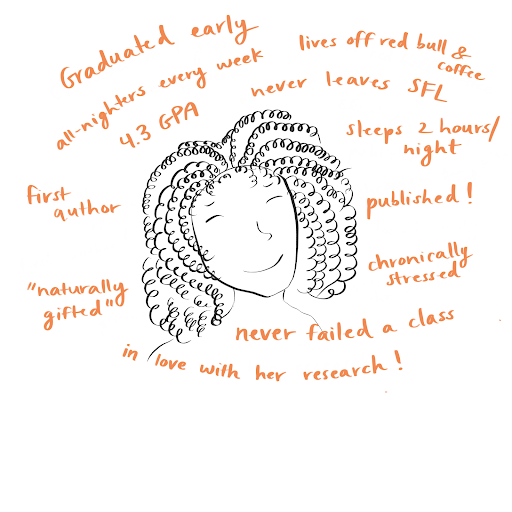

Many students seem to take a perverse pride in — or at least have a grim acceptance of — this toxic culture. Students and professors alike look with awe at those students who are able to excel without appearing to struggle. This attitude plays into widespread impostor syndrome (the feeling of being academically out-of-place) among the student body (as described in the 2022 Co-Curricular Group Report). Students feel that they “don’t belong here” if they don’t force themselves to maximize their accomplishments at the expense of their physical and mental health. As a result, poor sleep habits and poor work-life balance are marks of pride, representing the sacrifices we make to succeed. They demonstrate how much harder we are working than everyone else and “prove” that we aren’t impostors. A selfless devotion to the pursuit of knowledge at the cost of physical and mental health is the hallmark of the mythical (and perhaps unduly venerated) “Caltech Genius.”

The mythical "Caltech genius."

Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

Proper sleep hygiene is made even more challenging by work expectations that force students to prioritize completing their work over healthy sleep habits. At Caltech, most problem sets are expected to be done collaboratively. They are intentionally made more difficult than what one person can do on their own so that they are suitable for a group, which incentivizes students to work together and penalizes students for working alone. This system, paired with undergraduate work culture, promotes work habits that make healthy sleep patterns impossible. Groups are generally only available at night due to daytime classes and extracurriculars, so most work gets done between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m. In addition, many sets incorporate information taught up to the due date, so it often isn’t possible to work ahead of time. Classes at Caltech are also chronically “under-unitted,” meaning that the actual hours spent by students on the class far exceed the hours listed in the course catalog. While intending to create a collaborative environment, the assignment structure at Caltech inadvertently causes students to spend more time struggling through homework than thinking critically about what they have learned.

The time pressure undergraduates experience at Caltech forces students to choose between central aspects of the traditional college experience. A lot of undergrads at Caltech don’t go to lectures, and many that do are late or exhausted. I always found this puzzling — here we are with some of the most accomplished scientists in the world teaching us the secrets of the universe, and yet we can’t bother to get out of bed for class. But when every moment has to be strictly scheduled, and lectures aren’t essential to learn the material, it often becomes a choice between going to lecture or getting the work done. An hour of lecture could be used to edit a paper, work on a problem set, or even just catch up on the sleep missed because of a paper or problem set for a different class.

The culture of burnout at Caltech isn’t the fault of any one person or group. It’s systemic, and the students and faculty are complicit. The bad habits that students internalize and often glorify are both encouraged and taken advantage of by the way classes are structured. There is a general assumption that students will sacrifice sleep and career opportunities to get their coursework done, which in turn allows professors to assign more work. This environment of chronic stress and poor sleep makes learning that much harder, which makes assignments take longer, which creates more stress and worse sleep; the result is a cycle of unhealthy conditions.

The culture of burnout at Caltech leads students to question their value and sense of belonging within the establishment.

Illustration by Jennah Colborn for Caltech Letters

These habits don’t magically disappear with an easier workload or a different institution. I still find myself working at strange hours, struggling to get up in the morning, and taking on more than my share, even when my supervisors encourage me to put my mental health first. Without ingrained healthy work habits, I often find myself ignoring signs of fatigue and illness to get more work done. Having now worked at other institutions, I’ve seen how environments that intentionally prioritize the health and wellbeing of students and staff actually increase productivity and quality of work. I’m still unlearning the work and sleep habits I developed at Caltech, but I’m lucky to be surrounded by coworkers and supervisors who not only encourage me to take care of myself but model healthy work habits themselves. I’m grateful to have the experience I gained from Caltech, but it came at the cost of my health.

One night at freshman orientation, in 2016, an admissions officer got up in front of the assembled class of 2020 and told us that all of us belonged here, even though we might not feel that way. This school would be better served if the students and faculty believed this. That means structuring classes with the goal of most effectively teaching the information, rather than trying to weed out students who “don’t have what it takes.” That means both students and faculty recognizing unhealthy work habits as detrimental and encouraging and modeling healthy work habits. That means reevaluating class curricula to ensure that students are not expected to spend more than their unit load worth of hours doing work for classes. That means mindfully structuring classes such that students can easily understand the concepts rather than being mired down in busywork. Caltech is one of the most selective universities in the country, and everyone here has earned their place. Students deserve an environment where they are free to learn without sacrificing their health.