Three months after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the soon-to-be-world-famous scientist Albert Einstein signed a document, the “Manifesto to the Europeans”, which said:

The struggle raging today will likely produce no victor. . . .Therefore, it seems not only ethically fitting, but rather bitterly necessary that intellectuals of all nations marshal their influence such that terms of peace shall not become the cause of future wars.

This document was a response to the “Manifesto of the 93”, in which 93 German intellectuals defended German military actions in WWI. For Einstein, being a scientist came with a great moral, civil, and social responsibility. He thought politics was far too important to be left to politicians: he spoke out on several political issues in interviews, writings, and manifestos, and he joined both pacifist and Zionist movements. He was far more than just a celebrity of science and a genius who revolutionized our notions of time and space—which is why, more than any other scientist, he still fascinates and inspires people today.

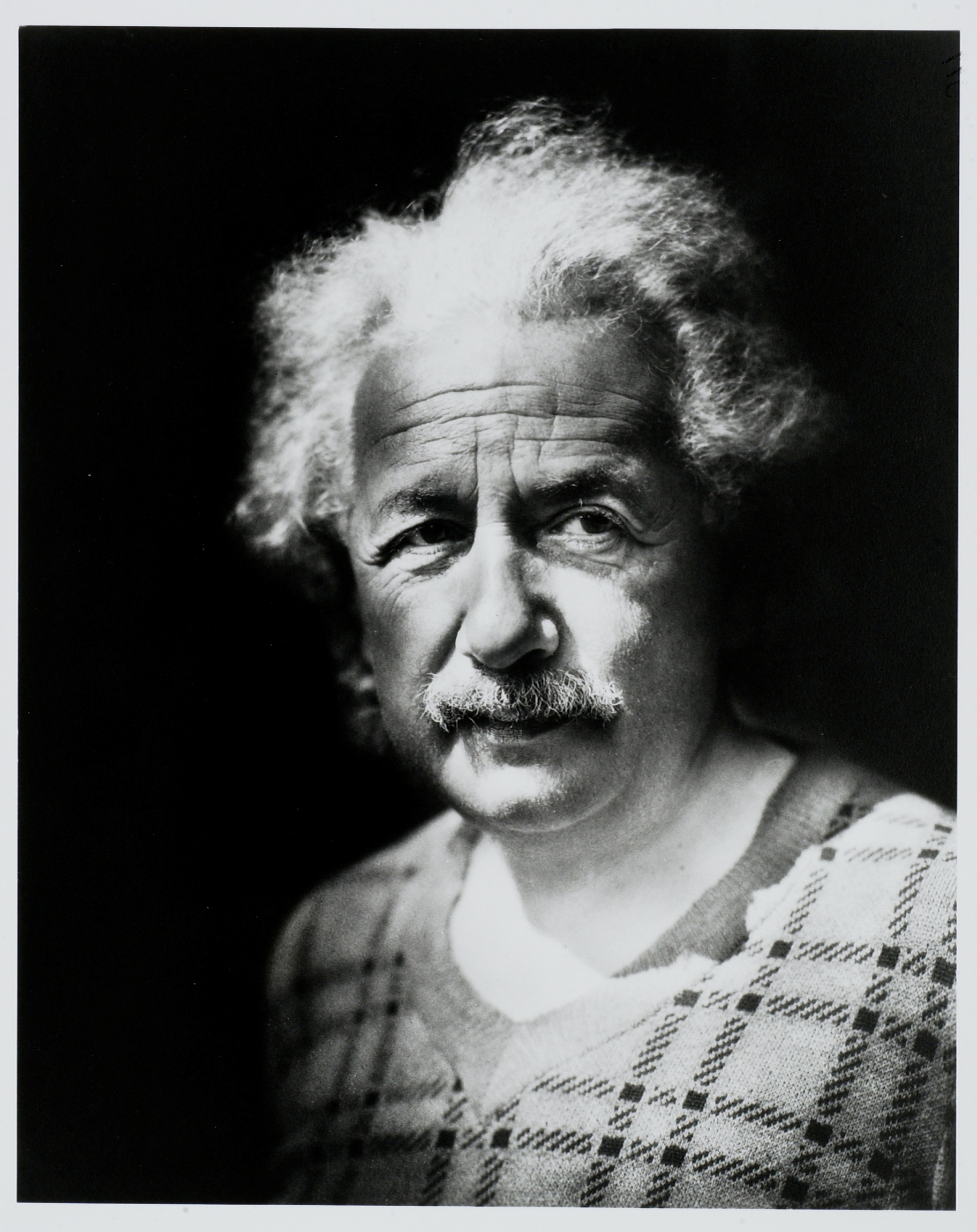

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) is seen here in a 1935 photograph.

Albert Einstein Archives

For this reason, a group of historians has dedicated their work to preserving Einstein’s written legacy and making it accessible to the public, enabling further research about him. This is the Einstein Papers Project at Caltech, where Einstein was a visiting scientist for three winters. The Einstein Papers Project is one of the most ambitious scholarly publishing endeavors in the history of science. The books that we publish, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, provide the first complete picture of Einstein’s enormous written legacy, including both published and unpublished writings, correspondences (personal and scientific), travel diaries, lecture notes, and personal documents.

One might wonder why an entire team of historians is needed to do this work, but don’t forget: Einstein was an incredibly productive genius. The amount of archival material we are working with is titanic: our online archive contains about 90,000 records and even now, a team continues to travel around the world scouring through archives for new sources.

Einstein’s mind is like a giant puzzle and our work is to piece it together from the scraps that remain. Therefore, we collect, transcribe, annotate, translate, and publish all of his writings. Since 1987, when the first volume was released, we have published 15 volumes that cover his life and work chronologically (so far, up to his 46th birthday). Stacking up all of our volumes makes a pile half my height. And once we’re done with the project, which will be in about 20 years, the pile will be taller than me.

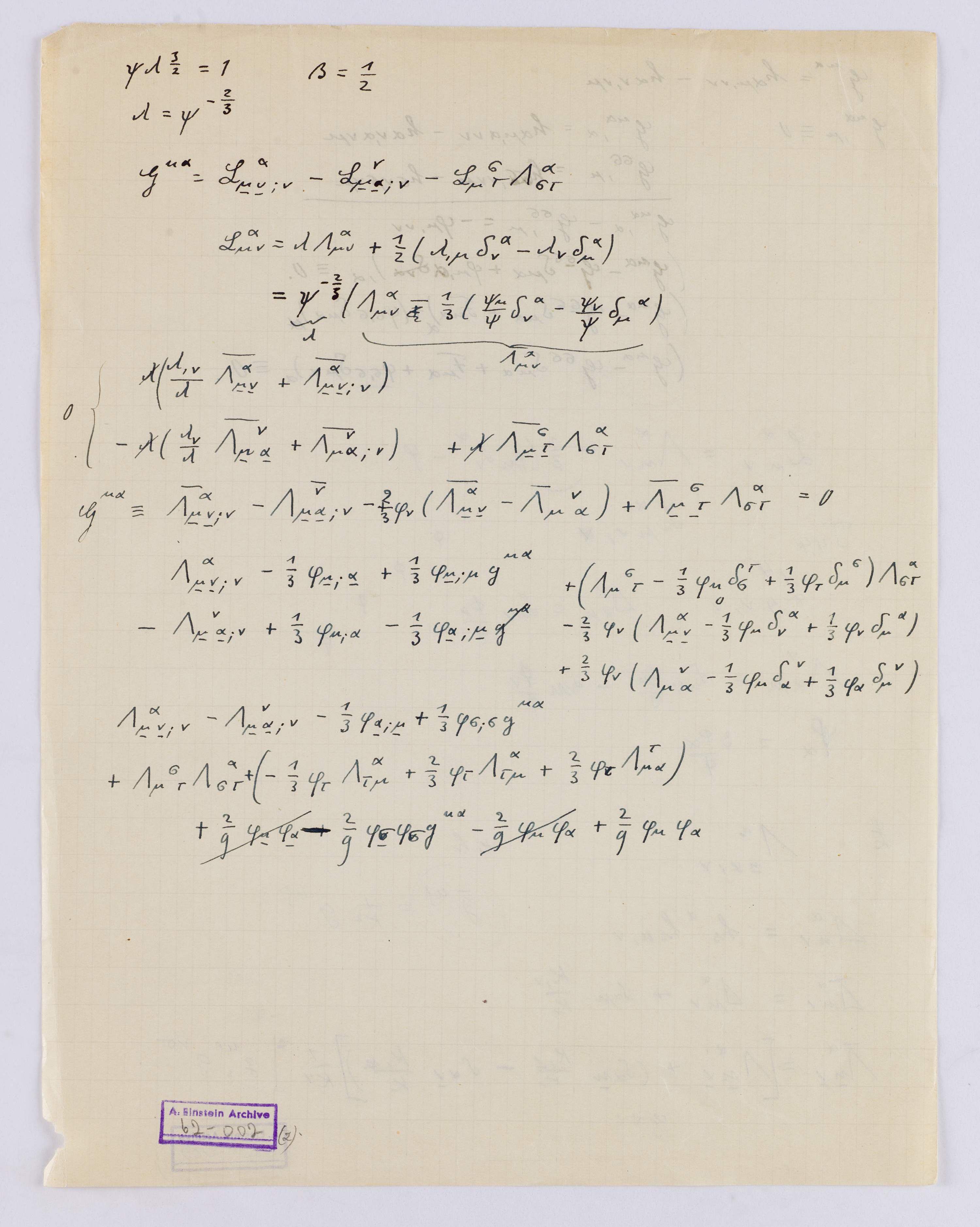

In 1982, when the archive was cleared to be transported to Jerusalem, a batch of some 1750 manuscript pages filled with scribbled calculations was found behind a filing cabinet. The pages were copied and saved as microfilms, but out of a lack of time and resources, no one had ever taken a closer look at them until recently (apart from relating them to Einstein’s approach to a unified field theory). Now our job is to find out what exactly this huge pile of mostly undated, single sheets is about. These research notes have a common characteristic of Einstein’s manuscripts: an abundance of mathematical formulae with barely any words that would explain his thoughts and help us understand it. But things like this are great—if not the best—evidence of the creative process behind his work. Therefore they are of immense value for historians of science. And who knows, we might find some of Einstein’s ideas in there that the world hasn’t heard of so far.

Notes about Einstein's approach to a unified field theory.

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

So, even decades after Einstein’s death, after dozens of historians, journalists and scientists have been trying to find out who Einstein was and what he did, we are still discovering many new things in every volume—like the undiscovered letters between him and his first romantic love, Marie Winteler, that were published in our latest volume. Working so closely with all of Einstein’s personal letters and writings as a historian has given me a unique insight into his private life and showed me different facets of his personality. I realized he was far more than a brilliant mind or a genius, for he played many roles in his life. He was a bumbling professor, a philosopher, a passionate sailor and pipe smoker; a poet, a man of great humor, a friend, a father, a husband and lover.

Einstein having fun.

Albert Einstein Archives

Studying Einstein, his life, and his work helps us understand human brilliance and how revolutionary scientific ideas were shaped—some of the core questions within the history of science. But also, studying Einstein can teach us something about the moral responsibility of scientists. And this is an aspect of his life that is especially fascinating and inspiring to me: his devotion to being an activist for peace, and his fight against racism, anti-Semitism, political oppression, and capitalism. His activism was more than just a hobby or an occasional coincidence, but rather an important part of his life and work. He had a strong disdain for war and all sorts of cruelty and oppression, and he devoted himself to the fight against them.

He was far ahead of his time with many of these things, but this did not stop him from being vocal about them, even at times when he could not find many like-minded people. He was one of the very few German scientists who opposed linking science to nationalism and the military during WWI.

In 1915, soon after the outbreak of WWI, he wrote to his friend and fellow peace activist Romain Rolland that “Even scholars in various lands have been acting as if their brains had been amputated.”

He openly opposed capitalism and the arms race during the Cold War at times when anti-communist hysteria swept over the US, which made this kind of activism very dangerous. He was even investigated by the FBI, and his file, which is now partially accessible on the internet, shows that they found him highly suspect.

For Einstein, war and militarism were incompatible with the dignity of free human beings. He was an anti-authoritarian, favoring nonviolent civil disobedience and conscientious objection. His belief in peace and socialism were never tied to a certain ideology, but rather, personal convictions and deeply-felt reactions to the injustice and cruelty of the world he lived in. He wrote in a letter in 1929,

My pacifism is an instinctive feeling, a feeling that possesses me because the murder of people is disgusting. My attitude is not derived from any intellectual theory but is based on my deepest antipathy to every kind of cruelty and hatred.

Yet despite his strong aversion to war and the military, he had a certain paradoxical lack of concern about military applications of his work, as he worked on airplane design and navigation for submarines through a gyro compass during WWI, and later happily agreed to working for the US Navy as an advisor for explosive materials in WWII. In his view, a world-threatening regime like Germany needed to be defeated—if necessary by military actions.

In 1939, he signed a letter written by other scientists to President Roosevelt where he recommended Roosevelt support research on a nuclear device, fearing that Germany might be able to build nuclear weapons first. Einstein’s warning probably had very little impact on the eventual decision to build an atomic bomb, which only began to be developed two years later. After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he reflected critically on this involvement, opining “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing the atomic bomb, I never would have lifted a finger.”

After WWII, he called vehemently for the banning of nuclear weapons and general disarmament. In 1955, shortly before he died, he signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, in which he and nine other prominent scientists enjoined for peace, the abolition of war, and nuclear disarmament by describing the destructive powers of the newly-invented hydrogen bomb. This was the last document he ever signed. Although Einstein did not live to see it published, his signature alone helped to raise public attention and awareness to the political problems of the Cold War and the threat of nuclear weapons.

Throughout his life, realizing the weight of his words, Einstein fought for his ideals, most importantly peace. But his life also draws attention to the tensions and moral conflicts that come with society’s use of scientific research. As Einstein’s life shows us, being a brilliant scientist is not an excuse to not get involved in politics, but is in fact a reason to do so even more.

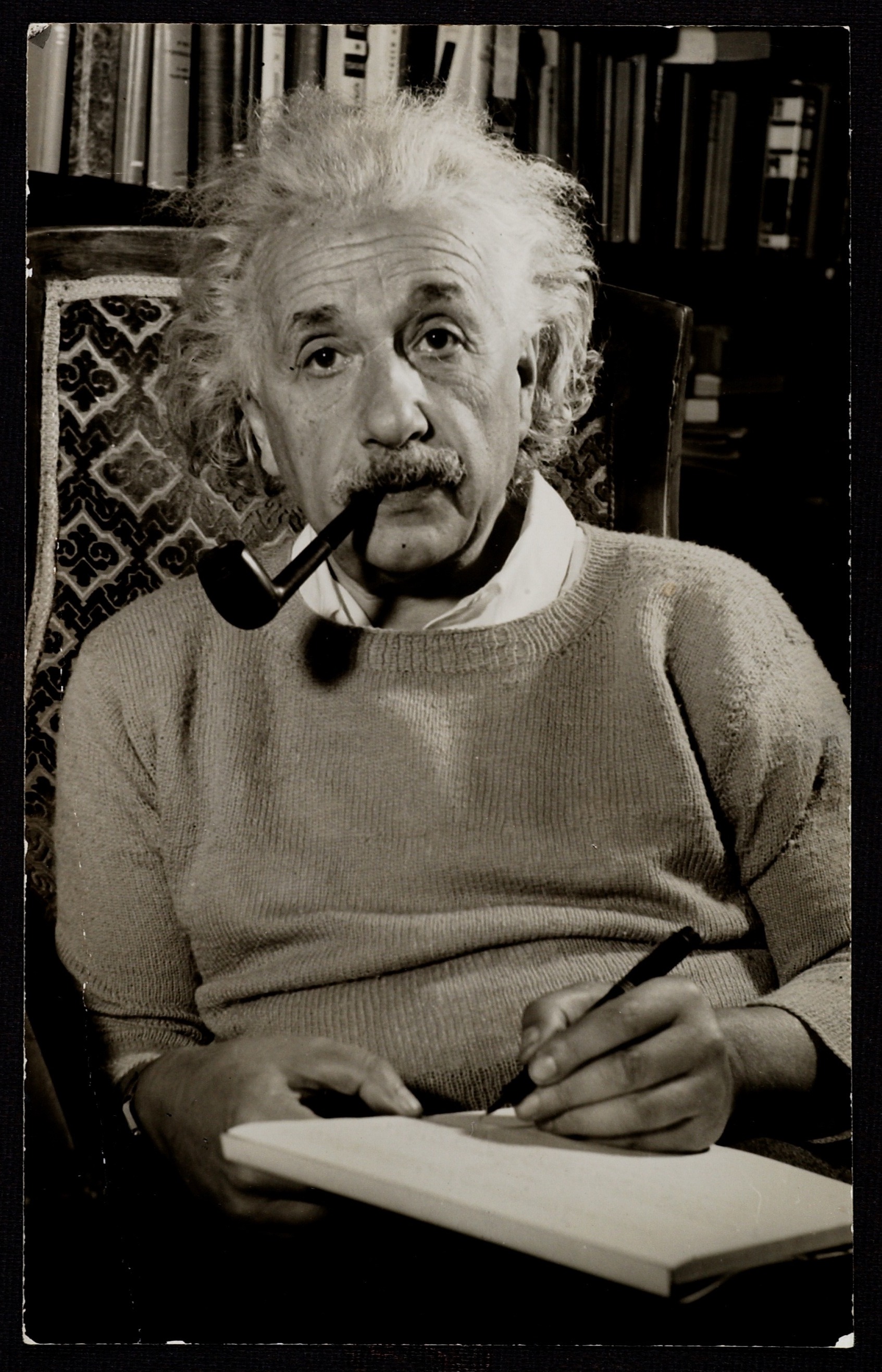

Einstein deep in thought.

Albert Einstein Archives

Curious to learn more about Einstein?

- Visit the website of the Einstein Papers Project.

- If you’re looking for a comprehensive biography, I would highly recommend Fölsing, Albrecht: Albert Einstein. A Biography. New York, 1997.

- For an encyclopedia that provides concise information about Einstein, his life and work: Calaprice, Alice & Kennefick, Daniel & Schulmann, Robert: An Einstein Encyclopedia. Princeton, 2015.

- Einstein’s views on peace are explained very well in the book Nathan, Otto & Norden, Heinz: Einstein on Peace. New York, 1988.

Quotations

- “The struggle…” Manifesto to the Europeans: CPAE, Vol. 6, Doc. 8.

- “Even scholars…” CPAE, Vol. 8, Doc. 65.

- “My pacifism…” Quoted in Calaprice, Alice The New Quotable Einstein, Princeton, 2005, p.156.

- “Had I known…” Quoted in Calaprice, Alice The New Quotable Einstein, Princeton, 2005, p.170.