The banana is an innocuous fruit on the verge of destruction. If you grew up during World War II, you may have had a Gros Michel for breakfast, but today you’d be hard pressed to find one. That’s because a fungus almost entirely destroyed Gros Michel bananas in the 1950s. They were replaced by the Cavendish banana, more than 100 billion of which are now sold each year.

But the Cavendish has a serious problem. Years of breeding have made it sterile, which means they’re unable to produce seeds of their own. They are also susceptible to a different strain of the same fungus that nearly wiped out the Gros Michel, which causes a disease known as Fusarium wilt. Humans have been selectively breeding plants for thousands of years, isolating desired traits to produce more delicious or larger crops. It was this selective breeding that made the Cavendish sterile, and nearly every other crop planted today has undergone a similar process, with farmers selectively planting only the plants that produce ample, edible food. It is only recently—in the last fifty years or so—that people could precisely choose which genes to introduce into a plant. This newfound capability comes, in part, thanks to a wave of technological advancements in genetics, including new tools to sequence DNA, synthesize DNA, and edit the genomes of living organisms.

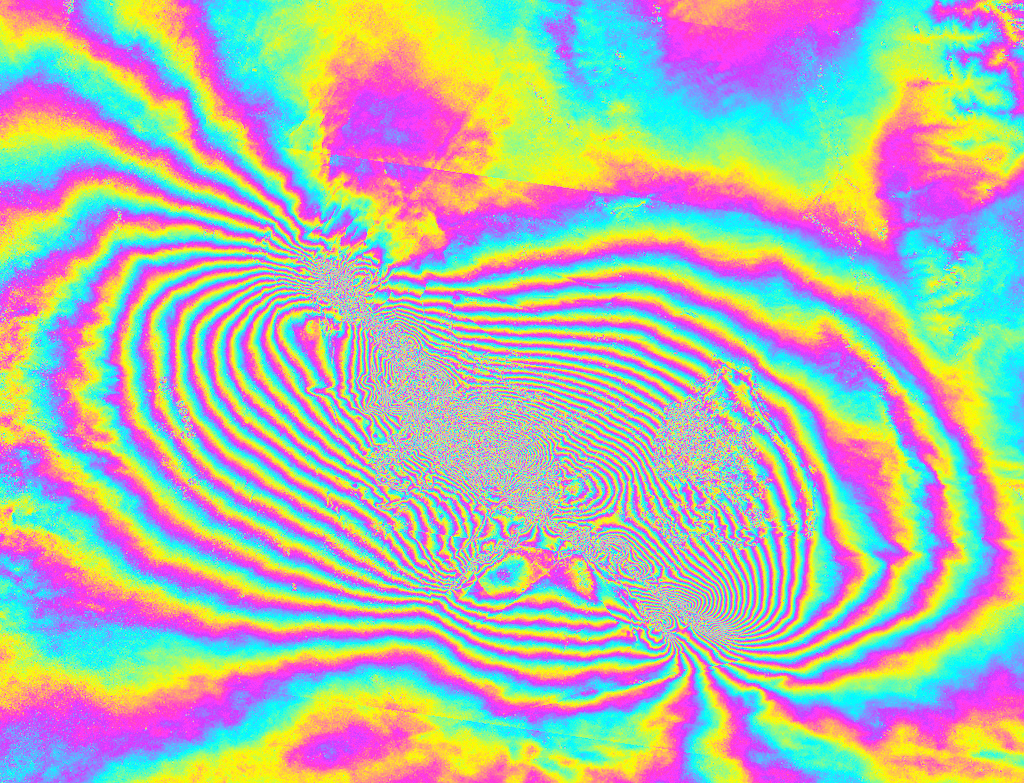

A banana plant with Fusarium wilt

Scot Nelson

With the Cavendish on the verge of destruction, scientists have devised a solution that relies on genetic engineering to save it from collapse. By taking DNA from a worm called Caenorhabditis elegans, which encodes a protein that protects cells from necrosis, and transplanting it into Cavendish seeds, they successfully created a banana that is completely resistant to Fusarium wilt.

These modified bananas come at a time of persistent fear, and widespread opportunity, for genetic engineering. Organisms with modified DNA are increasingly being used to fend off microbial invaders, protect crops, and enhance agricultural yield. But public concern persists. Surveys from the Pew Research Center show that 49% of U.S. adults think that GM (genetically modified) food is bad for their health.

This dilemma between “to engineer” and protect a crop, or “to not engineer” and defer to public opinion, at least in the case of the Cavendish, is a constant ethical struggle in the field of synthetic biology, a scientific discipline focused on the reading, writing, and editing of DNA in living organisms.

Every living organism has DNA, a string of molecules that functions as a blueprint for its behaviors, physical properties, and capabilities. Humans, whose full genome includes 3 billion ‘letters’ of DNA, can digest food because DNA within our cells encode proteins that break down sugars and fats. That same genome also encodes proteins in our eyes, which capture photons and help our brain discern images. Now, we have the power to edit the blueprint of living organisms, including bananas and human embryos. But none of this would have been possible without the work of Paul Berg.

In 1971, Berg, then a faculty member at Stanford University, took a bit of DNA from a virus that infects bacteria, called lambda phage, and spliced it into the DNA sequence of a cancer-causing virus that infects monkeys. The result was the first piece of “recombinant” DNA—a genetic sequence created from two different organisms. Berg’s experiment demonstrated the remarkable reality that DNA, no matter its source, is a universal blueprint for life. It can be transferred between organisms, and can still be recognized and ‘read’ by the recipient cell.

Dr. Paul Berg, recipient of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Wikimedia Commons

After Berg reported his findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 1972, there was widespread concern amongst scientists that the recombinant DNA could place the health of scientists at serious risk. In response, the world’s leading geneticists assembled at Asilomar State Beach, on the Monterey Peninsula, to write up guidelines that would inform genetic engineering and recombinant DNA research. They called for some restrictions, including a ban on experiments that sought to make recombinant DNA from disease-causing organisms. These restrictions would not hold back the tidal wave of technological breakthroughs to come. Soon, scientists had developed molecular tools to read, write, and edit DNA, offering unprecedented control over life’s blueprint.

Our newfound mastery over biology was demonstrated in a tour de force research article in 2000. Confined to the final pages of the January issue of Nature, it heralded a paradigm shift in biology that would come to define the promise—and worries—first set out at the 1975 Asilomar conference. What if scientists could endow organisms with entirely new behaviors not found anywhere in nature?

In this issue of Nature, scientists reported the first successful genetic circuits operating in living cells. Modeled on electrical circuits, researchers constructed biological circuits in living organisms with recombinant DNA, an accomplishment that went well beyond transplanting a single gene between species.

One of the circuits, called the repressilator, programmed bacterial cells to glow green, on and off, every 150 minutes. They repeat the cycle again and again in a brilliant, chaotic dance. This study marked the dawn of synthetic biology, a scientific discipline devoted to large-scale genetic editing of living organisms.

Scientists (and the media) quickly took note. A skilled group of physicists, bioengineers and molecular biologists soon flocked to the emerging discipline, eager to engineer cells that could perform ‘unnatural’ functions. In the years that followed, engineered cells were processing and recording information, executing complex behaviors (such as counting and forming patterns spontaneously), and even converting inexpensive starting materials, like sugar, into valuable medicines.

Today, scientists can engineer organisms to produce just about any chemical, from fuels to medicines, if they are able to do two things:

- Create DNA sequences that encode proteins to make those chemicals, and

- Get those DNA sequences into, and read by, the organism.

Though it sounds challenging, both of these have become remarkably simple in the last two decades. Custom DNA sequences can be ordered from companies, shipped to your door, and then transplanted into microbes in a single day. These rapid advancements have heralded the rise of genetic engineering en masse.

Despite our newfound ability to engineer life, many do not agree that we should engineer life, nor is the public always aware of what genetic engineering and synthetic biology actually entail. Studies from the Pew Research Center found that 19% of U.S. adults “have heard nothing” about genetically modified foods. Strikingly, 17% of U.S. adults also say that “none of the food they eat has [GM] ingredients,” despite the fact that 94% of all soybeans grown in the U.S. are GM and 89% of all corn in the U.S. is GM (according to the USDA).

But despite the prevalence of GM crops, hundreds of studies over the last few decades have repeatedly affirmed their safety. Eating engineered crops does not cause mutations in our genomes, nor does it affect the health of any of our organs. Despite widespread fears, GM foods also do not cause any changes in a woman’s fertility or offspring. In short, they are completely safe, and perhaps more importantly, they are helping to feed a swelling population.

Over one billion people suffer from micronutrient deficiencies, the most prevalent of which is vitamin A deficiency. This vitamin helps with vision and the immune system, but access is limited. In Southeast Asia, researchers have used genetic engineering to produce a new strain of rice called Golden Rice. Tinged yellow, this engineered rice could provide the vitamin A that billions of people need. Genetic engineering has also made crops that are drought-resistant and can fend off invasive bugs without pesticides.

But synthetic biology is not limited to agriculture; it is deeply impacting the fuels we burn, the clothes we wear, and the medicines we consume. The global supply of human insulin to treat diabetes is almost exclusively produced from genetically-modified bacteria. Some clothing companies have also created engineered microbes that produce synthetic silk fibers, removing the laborious effort involved in tending silkworms. Still others have engineered microbes to capture carbon emissions from factory waste and convert it to ethanol, a feat that is expected to reduce emissions comparable to removing hundreds of thousands of cars from the road each year.

Despite public concern, synthetic biology is here to stay. It offers a deeply powerful approach to science, enabling researchers to bend organisms to their will, and harness them to tackle some of the most pressing challenges facing our planet. In agriculture, delicious crops that once took thousands of years to breed can now be created in just a few months.

In the years to come, synthetic biology will enable us to do far more than just save the Cavendish—it will usher in a new era of mastery over nature, with DNA engineering at the helm. When a food, like the Cavendish banana, falls in danger because of climate change, drought, or disease, scientists can jump to the rescue and develop strategies to save them. But this power—and protection—comes at an ethical cost, with scientists dictating millennia of evolution in a single experiment. Science is not done in a vacuum; it is an intimate relationship between researchers, benefactors, and those who stand to benefit. Everyone should have a say.