As our tiny submarine sinks, the sunlight fades. Around 100 yards deep into the ocean, the darkness encompasses us—and we still have 3000 feet left to descend. A few points of light puncture the darkness as we pass through clouds of animals, most likely jellyfish or their relatives. Their ghostly shapes twinkle and shimmer in the dark, silent as stars—perhaps to communicate, attract prey, or for some other arcane reason altogether.

Illustration by Emma Sosa for Caltech Letters

Some say that we know more about the furthest reaches of our galaxy than our own oceans. While this statement is a bit exaggerated, it is true that we have better maps of the Moon, Venus, and Mars than the ocean floor. Only about 0.05% of the seafloor has been mapped with high-resolution sonar—about the same fraction as the area of Rhode Island compared with the continental United States. Even less has been observed by the human eye, so it is no surprise that we have little understanding of the complex interactions between oceanic lifeforms and their environment.

Work in the 1840s by the British naturalist Edward Forbes initially portrayed the ocean as a vast, lifeless desert. It took over a hundred years to correct that first impression, but we now understand that the ocean floor is far more complex than Forbes could have ever imagined. Even in the most nutrient-poor areas, ocean sediments are filled with microorganisms like bacteria, archaea, and other single-celled organisms. Without sunlight readily available as an energy source, these organisms eke out an existence in the cold depths by consuming marine snow, particles made of decaying surface organisms and other debris which gently sink down to the seafloor. Perhaps one “snowflake” is a globule of bacteria, while another is a crumb from a shark’s lunch.

Forty-five minutes of slow sinking later, we arrive at our destination: the ocean floor. For the next eight hours, we will eagerly observe, sample, and document our surroundings, seeing parts of the earth no human eyes have witnessed before. Our submarine is the legendary Deep Submersible Vehicle (DSV) Alvin, operated out of the research ship Atlantis. Alvin has explored the Titanic, discovered the first underwater hydrothermal vents, and examined the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, but the purpose of our dive today in this fabled vehicle is to explore a methane seep west of Costa Rica and the many fantastic animals and microbes that inhabit it.

Alvin selfie in the deep: Alvin collecting experiments in an inactive region of the ocean floor. The camera was mounted on an “elevator,” a sample platform with easily detachable weights. The elevator is sunk prior to Alvin, loaded with samples, and released to the surface to allow for early sample retrieval by the shipboard scientists.

Crew of AT37-13 and AT42-03

Typically found close to tectonic plate boundaries, methane seeps are the result of one plate sliding under another. As the lower plate heats up, a host of volatile chemicals are released from their rocky prisons and flee to the surface, including dissolved metals like gold and platinum as well as greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide. The methane-rich fluids either escape explosively at dramatic vents—appearing as plumes of white or black “smoke”—or more gently at seeps, where they invisibly trickle into the seafloor sediment.

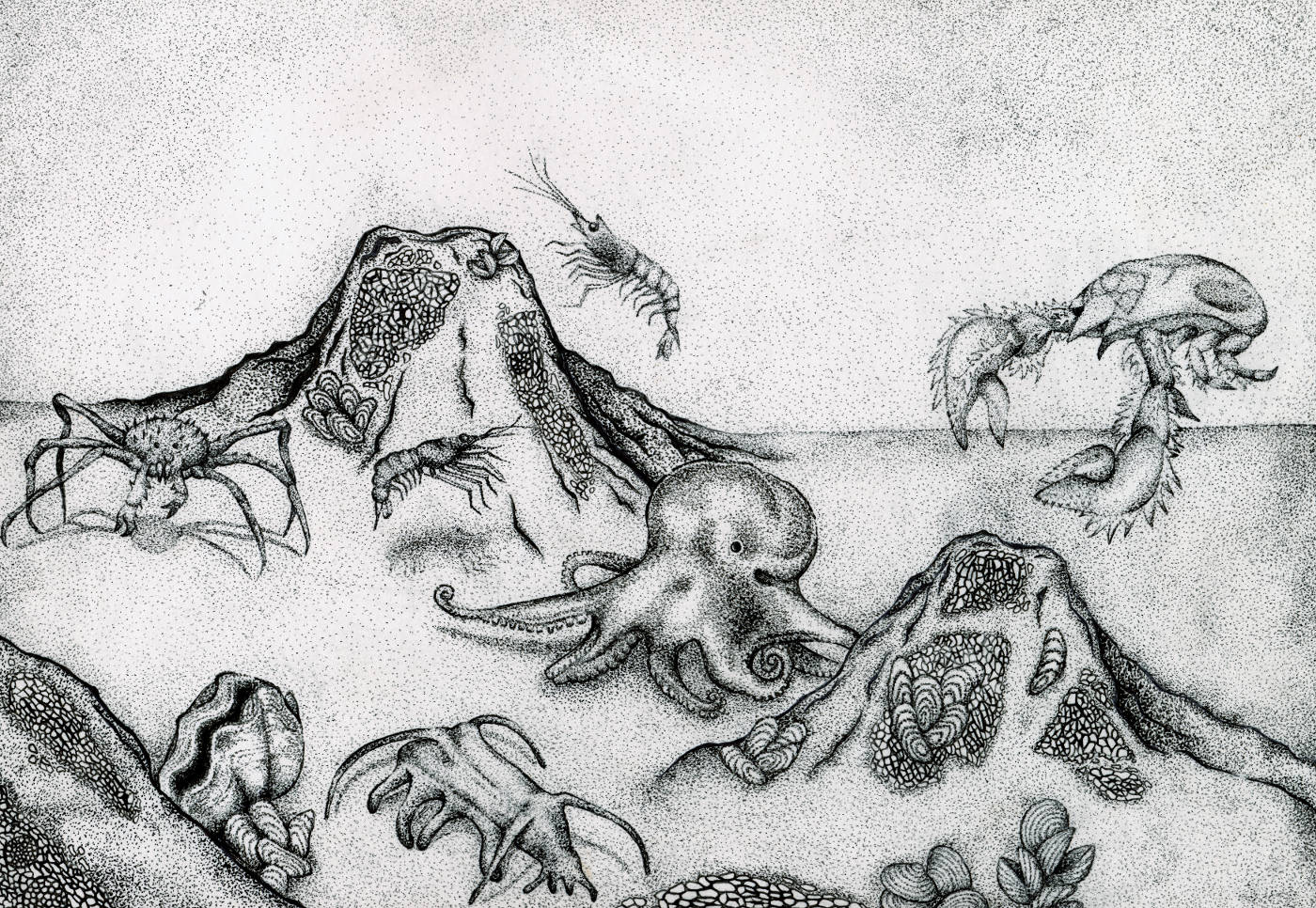

At both vents and seeps, the quantity and vibrancy of life is much greater than the rest of the deep ocean. The methane at these sites is the fundamental energy source for the food web at these communities—no sunlight necessary. In the darkness, bacteria and other tiny lifeforms have evolved to consume the methane and breathe sulfate (an abundant chemical in the oceans) the same way you would eat a sandwich and breathe oxygen. A host of fabulous animals like worms, snails, and sea pigs, a type of sea cucumber, act as herbivores, eating the methane consumers as their main food source. Other animals like tubeworms, mussels, clams, and yeti crabs farm their own species of microbes on their bodies using the waste of methane consumers like manure in fertilizer. Yeti crabs are particularly interesting. They grow their bacteria on special hairs on their arms, and to give their microbe farms a little extra food, they “dance,” waving their arms to the beat of methane flux from the sediment. Thus, the collective noun for a group of yeti crabs is a “party”.

A party of yeti crabs on the ocean floor

Sean Mullin

A variety of other species that do not feed directly on the methane-consumers also reside close to the seeps, including beautiful octopi, worms, crabs, and shrimp. These organisms are connected to the food web in other ways. Some are predators, hunting the microbe-eating herbivores, and others are scavengers, living off the scraps of the predators.

If the ocean floor is a watery desert, methane seeps and vents are the oases, attracting a diverse collection of organisms from the surrounding area. Our research in Costa Rica is aimed at understanding the sphere of influence around a seep and exactly how the local microorganisms impact the broader seafloor community. This is a difficult question to thoroughly answer since new species are discovered virtually every time another seep is explored. Our team of scientists not only characterizes the new species, but also how it interacts with other organisms. To that end, we use the many cameras, containers, and sampling devices on the Alvin to collect sediment and rocks rich with animals and microbial communities so we can study them in our shipboard laboratory.

Mussels and clams are frequent inhabitants of methane seeps, but the mussels here are different from those you would find close to shore. Instead, these mussels host sulfide- or methane-eating microbes within their gills, which provide food for their host in exchange for protection via the mussel's shell. You can also see many other typical inhabitants of a methane seep here, including galatheid crabs and shrimp, serpulid worms (the little white tubes on the rocks), and even a couple of yeti crabs (center at the very top and just right of center). Serpulid worms and limpets (aquatic snails) also dot the shells of the mussels, but everything else sits atop a large carbonate rock, which is a byproduct of the methane-consuming microbes.

Crew of AT37-13 and AT42-03

Although there are now a number of submarines and remote-controlled vehicles dedicated to oceanic exploration, the Alvin program was the first. In truth, this is the third version of Alvin to exist. The first, constructed back in 1964, had only a fraction of the capability of the newest, but the basic design has remained the same: interior chamber, thrusters, a handful of small viewports, and a sample collection arm. The most important feature is the 11,000 pound, 7-foot diameter titanium bubble that houses the three people diving: one pilot and two scientists. It is nearly a perfect sphere—the best shape for handling the tremendous pressure at the ocean floor—an engineering marvel in its own right. Alvin is designed to be fully functional 21,000 ft deep, where the pressure is 637 times higher than at the surface. In an attempt to ward off my nerves about descending to such depths, a pilot once told me, “There’s really no reason to be worried. At that depth, if the sphere fails, you’ll be crushed before your brain can even register that it’s happening.”

It didn’t help.

But the greatest danger isn’t pressure, it’s fire. The sphere is chock-full of electronic equipment, from GPS and sonar to 4K cameras and the haptic feedback controls for the many-jointed arms that collect samples; in the tight quarters, a fire could be disastrous. Oxygen concentrations in the cabin are kept purposefully low to help smother any fire, about 10% lower than the atmosphere, despite the wicked headache this gives the occupants the next day. Thanks to the many precautions taken by the Alvin engineers, the program boasts an impressive safety record. In more than 5,000 dives, there has never been an instrument problem that prevented the recovery of the Alvin and all souls onboard.

Our lab will make good use of the hundreds of samples we obtain during the 21 Alvin dives we take on this particular expedition, but such progress comes at a significant cost. Diving in the Alvin costs about $45,000 per day, not including any scientific personnel or data processing costs. So why do yeti crabs and worms, cute as they may be, warrant such a huge investment for scientific study?

Because most people will never see these creatures in their natural habitat, the ocean floor may seem like it has little impact on the day-to-day lives of humans. In reality, the methane-consuming communities that occupy these seeps are vitally important for maintaining the global climate. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas; a molecule of methane added to the atmosphere traps about 20 times more heat than a molecule of carbon dioxide. Fortunately, 80–90% of the methane produced in the oceans is consumed by the organisms at these seep sites before it ever reaches the atmosphere. Without these organisms, the amount of methane entering our atmosphere every year could increase by almost 20%, with disastrous effects on the global climate and life on the surface.

Unfortunately, we aren’t the only visitors to these seeps and vents, and today these fragile, vital environments are under threat. The hydrothermal fluids that carry the methane from the melting tectonic plate upward are also laden with gold, platinum, and rare-earth elements like lithium. In a world increasingly powered by lithium batteries, vents and seeps are attractive prospects for mining operations. According to the United Nations, the seafloor in international waters is the “common heritage of mankind” and is therefore protected. Many seeps, however, lie in waters directly controlled by particular nations, and vent mining operations have already started in a handful of locations. As we continue to gather more information on these deep-ocean communities through our adventures in the Alvin, we are beginning to understand how detrimental mining operations can be to ocean life. One of our recent discoveries, unfortunately, is that methane-consuming organisms do not exist at appreciable abundances anywhere beyond the region of methane seepage. If mining operations continue to seek out lithium and other metals in the main areas of methane seepage, they are likely to disrupt the microbes that are the bedrock for the entire seep community and responsible for preventing a catastrophic amount of methane from entering our atmosphere.

Characterizing these environments is a vital first step in preserving them, but we must also convince the general public that these sites are worth saving. The deep sea scientific community has recently made strides to share data and video of these locations and the amazing creatures that inhabit them to inspire people to want to preserve these sites. Our hope is that we can change hearts and minds, one dancing yeti crab video at a time.

Check out the following articles for further information about the history of ocean exploration, life in the methane seeps, and the evolution of the Alvin ship:

The Beginnings of British Marine Biology: Edward Forbes and Philip Gosse

What it’s like to hunt for life at the bottom of the ocean

Modifications on the Alvin Ship