Folks in California have heard it before: The “big one” is due any day and we’d better hope our cities are ready. Fortunately, decades of research from universities, civil engineers, and government organizations like the U.S. Geological Survey have outlined where and how to build appropriately. Building codes and standards ensure that most structures should withstand the shaking when it comes, and there’s strong evidence that these building codes work.

But can we be doing better? What’s the right way to define and measure earthquake hazards, to communicate probabilities to the public, or to design better buildings? New research has pointed to at least one assumption that can (and should) be challenged, but the solution has been buried in scientific literature for decades.

Scientists and engineers don’t always approach things the same way. Often this difference in philosophy is a productive thing, but what happens when lives are on the line? When it comes to earthquake hazards and the design of appropriate building codes, we don’t always have the luxury of a second chance.

A simulated earthquake for southern California, where colors show the shaking waves radiating from the San Andreas fault as it ruptures. The Southern California Earthquake Center and U.S. Geological Survey put together this “Shakeout Scenario” to inform the public and policy makers about the possible earthquake.

Robert Graves, Southern California Earthquake Center

Different Approaches

Scientists working on earthquake hazards strive to make the world safer. We try to understand the basic properties of the earth and how earthquakes occur. We seek to forecast how the ground will shake once earthquakes do occur (how strong, how long, and at what frequencies). It is our sincere hope that someday our equations and journal articles will trickle down to society in a manner that will save lives.

Yet even with that sense of purpose, too often I have seen scientists fail to engage or fail to connect with those who will actually implement the work further down the road. We make a pretty map or plausible theory, get our journal publication, and move on to the next project as our grants and careers require. Surely, we think, someone else will read the theory, recognize its importance, and design cities appropriately. It is our belief that engineers will come to see the world as we do, without us pausing to consider that we may need to explain things differently or ask their opinions. Oftentimes, the scientists are not even asking the right questions from the perspective of an engineer.

In contrast, engineers approach the problem systematically, empirically. The ground shook in the past, so we make measurements and fit a line, then use this to make things safe for the future. This approach is rooted in necessity and a good dose of realistic apprehension; the real world can’t sit around and wait for a new theory. Scientific models may change every few years, but a building should last for a century or more. Lives are on the line. An answer is needed now, and we do the best we can. Many engineers engage with basic researchers to guide this answer, but there are still cases where decades worth of theoretical developments are left on the shelf.

The Earthquake Threat to LA

Here’s an example of an opportunity for improvement. Before any building is constructed, some measurements of the soil and rocks beneath it is necessary. Soft sands and soils will shake more strongly than granite. The basic assumption is that earthquake waves will propagate vertically from below—if we know the layers of the geologic structure, then it is a straightforward physics problem to determine how any inbound seismic wave will amplify and resonate. Conservation of energy dictates that as the velocity goes down, amplitude goes up in the same way that waves at the beach get taller and slower as they approach the shore before breaking. Many cities (including Los Angeles) are built on top of sedimentary basins with low seismic velocities, meaning they are prone to large shaking. Broadly speaking, we’ve known this for decades, and every building in California must meet building codes accordingly.

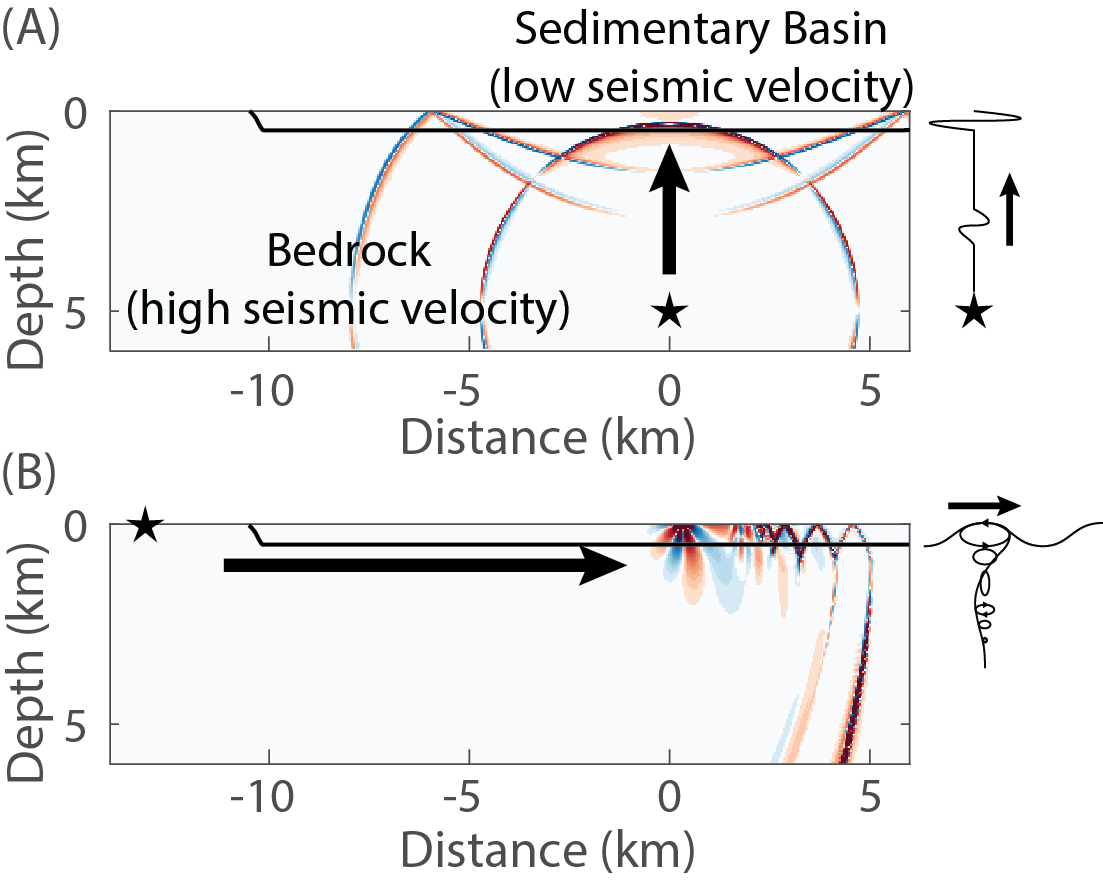

But let’s break this down further, and consider the assumption of a vertically-travelling wave. On many scales and in many places, this is a very good and appropriate assumption, especially when earthquakes come from a large distance away. It is effective; it gives the right answer. But what happens when earthquake waves propagate into a sedimentary basin from the side, travelling along the earth’s surface, instead of from below? This is the case for a large earthquake that might occur on the San Andreas fault east of Los Angeles. We’ve known about these surface propagating waves for a long time, dating back at least to the Victorian scientist Lord Rayleigh in 18851. Conservation of energy may be a slightly more complicated equation for these surface waves, but even this has been described at least as far back as 1961 by the geophysicist John De Noyer2. Yet this equation is missing from much of our engineering practice.

Diagrams showing two scenarios, with an earthquake source marked by a star. (A) An earthquake immediately below a sedimentary basin, where waves come in from the bottom. (B) An earthquake occurring near the surface outside the basin and moving in with strong surface waves from the side. Most models assume the behavior in (A).

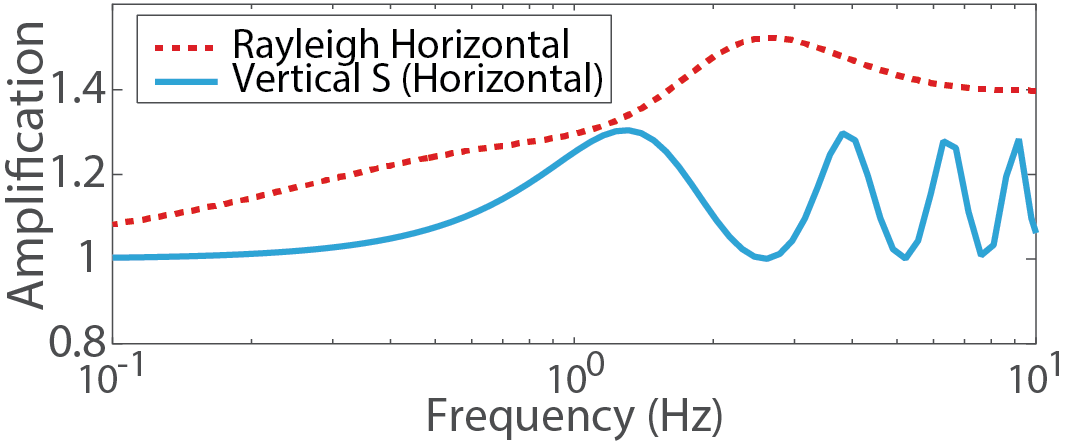

Bowden and Tsai 20173

Scientists have dropped the ball. We’ve watched an industry develop on the premise of only vertically-propagating waves. Countless studies have been performed and even entirely new methods have been developed to measure the earth on this assumption. Characterizing the geology beneath a new proposed construction site is required for this reason. Ask almost anyone in this field how this is implemented and you’ll get exactly one answer. The blue curve in the image below shows how the incoming vertical wave will amplify and resonate in a deep sedimentary basin like Los Angeles (this blue curve is the standard assumption). But in the situation of strong surface waves entering from the side, our research has shown a very different picture: the red curve shows that this type of wave will be more strongly amplified and at different frequencies. This will make a difference in how buildings are designed, and which kinds of buildings are more susceptible to damage.

The effect of slow seismic wave speeds in the sedimentary basin will be different for the two types of waves. The red line shows the amplification of waves coming in from the side, while the blue line shows the same for waves coming in from below. Larger amplification means more shaking during an earthquake.

Bowden and Tsai 20173

There’s no need to panic yet—it’s not that everyone just ignores surface waves. Your buildings are still safe; building codes do account for a wide range of possible scenarios. The agnostic, practical way of thinking is to acknowledge that surface waves have affected our past measurements and so they’re being accounted for in the datasets. If the statistical regressions were made using data from both types of waves, then in some sense we’re covering our bases. For other researchers, this is precisely why the right path forward includes supercomputer simulations of the earthquakes that do inherently capture every type of wave, like the ShakeOut scenario from the video near the top.

But at the basic level, we’re not approaching this challenge in the right way. Complicated statistical regressions with corrective factors don’t fix the problem that we’re not considering the right basic physics. If both types of waves are present in our datasets, fitting a single curve to the data will undoubtedly be messy (as evident in the previous image, there should be two curves). We need to take a step back and think about the problem. If surface waves pose a threat (again, they certainly do for L.A.), let’s define conservation of energy according to the right physics and go from there.

Working together

In this example, science and basic research offers an improvement that has yet to be reviewed or implemented by the engineering community, even though the science has been known for more than 50 years. Is this the engineers’ fault for not being properly well-read? Or is this the scientists’ fault for failing to communicate its importance? I really don’t care, as long as we can work together to fix the problem. What I have learned is that speaking to both camps is confusing and difficult, but we have to make it happen.

The same goal can be said of many fields. Medical researchers, neuroscientists, neural-network programmers, nuclear physicists and others (all of us really) have an ethical responsibility to think about how our science will affect the real world. Publishing in an academic journal and just “hoping for the best” is not sufficient, regardless of our good intentions. Just because we scientists don’t always deal directly with applied consequences does not absolve us of responsibility.

References

1: Lord Rayleigh (1885). On Waves Propagated along the Plane Surface of an Elastic Solid. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, iv(42).

2: De Noyer, J. (1961). The Effect of Variations in Layer Thickness on Love Waves. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am., 51(2), 227–235.

3: Bowden, D. C., & Tsai, V. C. (2017). Earthquake ground motion amplification for surface waves. Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL071885