Illustration by Casey Yamamoto, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

There is a saying in Chinese that translates to “every medicine is thirty percent poison.” I was brought up in a family that subscribed to this philosophy. When my doctor prescribed me a buffet of pain relievers after I got my wisdom teeth removed in the US, my parents urged me not to take them. They believed taking pain killers would burden my liver, and the temporary disappearance of pain would mask any symptoms of a potential complication. Their reasoning is rooted in the belief that medication is not needed for every discomfort—you do not need to take pain medication, unless the pain is life-threatening. Raised in this environment, I was shocked when I arrived in the US and saw the casual attitude people have toward pain relievers, as well as the prevalence of pain medication misuse among Americans.

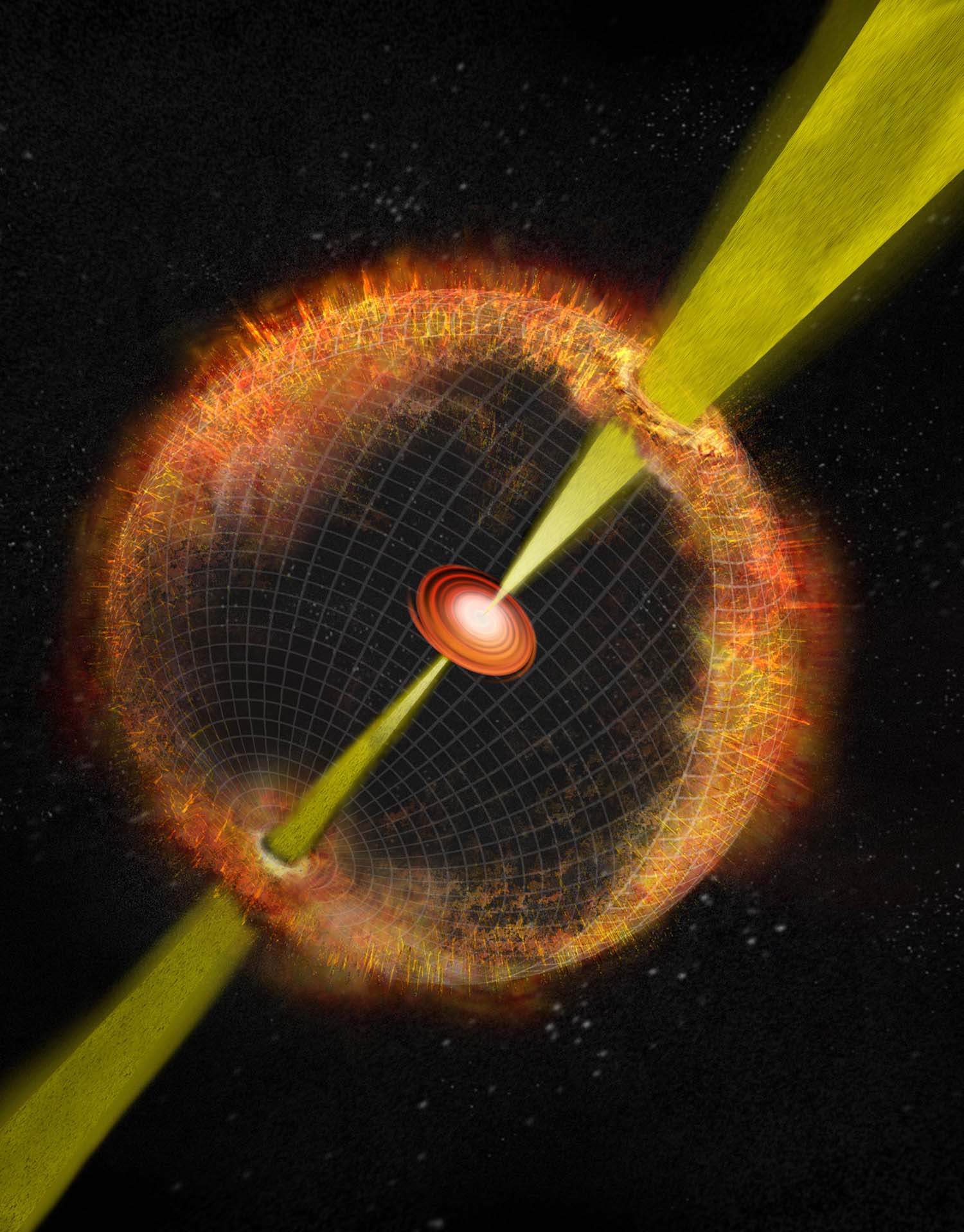

I reflected upon the different attitudes the US and China have towards medicine as I began my most recent project characterizing opioid misuse in the United States. Opioids are a class of drugs widely abused in the United States and are typically prescribed to treat moderate to severe pain. Opioids cause a sense of euphoria, a “high” that not only dulls the pain of the body, but also has psychoactive side effects. Long-term use of opioids creates dependencies and can lead to addiction. The United States has more people with opioid use disorder than any other country in the world. In 2017, 1.7 million Americans suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioids and approximately 47,000 died as a result of an opioid overdose. The issue is more severe today than ever, as the pandemic and isolation exacerbates feelings of loneliness and despair, causing some people to turn to drugs as a coping mechanism.1

Top: Overdose death rates in the United States involving opioids. Bottom: Countries consuming most opioids from 2013-2015.

Data from the CDC and the UN International Narcotics Control Board (see references 2 and 3)

There are many brands of prescription opioids that are manufactured and sold, but OxyContin is by far one of the most popular. OxyContin was launched in 1996 by Purdue Pharma (also known as “Purdue”), one of the major culprits behind the opioid crisis. OxyContin was a unique approach because it provided round-the-clock pain management from a single pill. One pill contained enough medication for several hours, but the innovative extended release formulation slowly delivered oxycodone, the active ingredient. Purdue spent a huge amount of money marketing OxyContin, and the company became a financial success in the 1990s and 2000s. In 2009, OxyContin accounted for 34.3% of all oxycodone pain relievers sold in the United States and 83.3% of all high-dosage pain relievers.4 While the drug was intended to optimize patient care, the large amount of oxycodone packed in a single pill made the drug one of the most popular opioid products to abuse. Users could crush and snort the OxyContin pills to get an instant high.

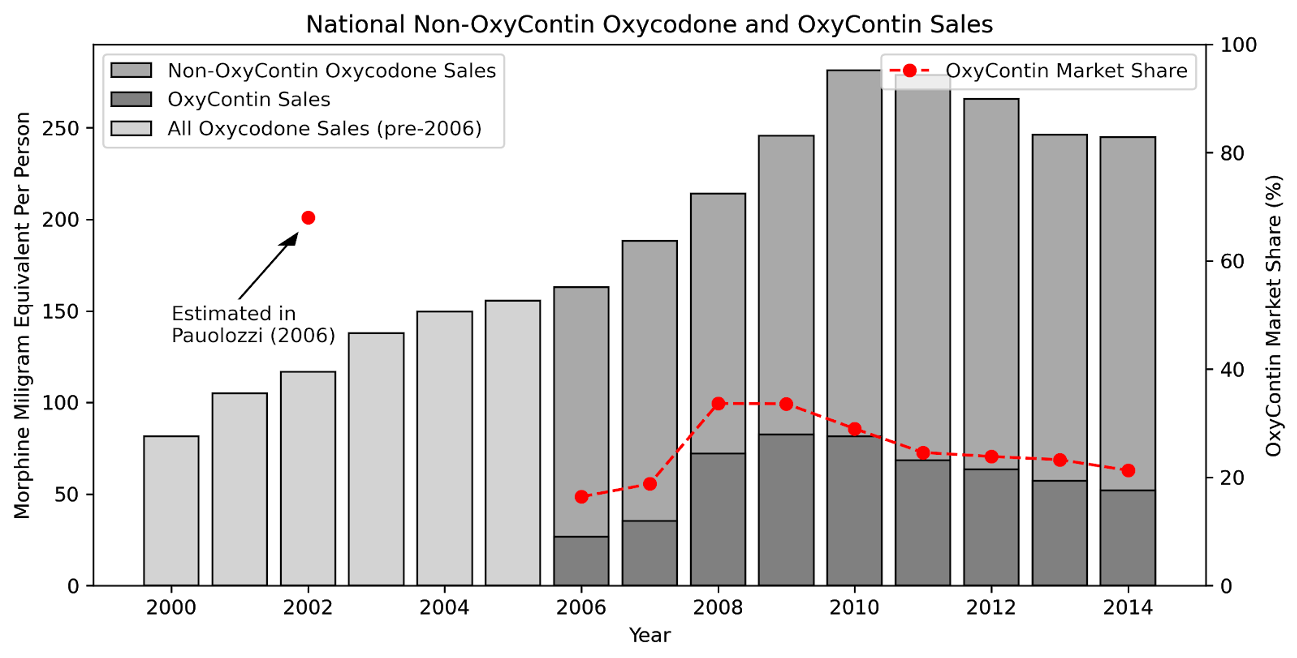

Trend in Oxycodone Sales: Sales of all prescription oxycodone increased substantially from 2000 to 2010, with per-person sales quadrupling in the 10 year period. The sales of oxycodone declined from 2010 to 2015 as a result of the OxyContin reformulation and aggressive measures taken by the states and the federal government to counter opioid addiction.

Shiyu Zhang and Daniel Guth (see reference 4)

In August 2010, under pressure from policymakers, Purdue reformulated OxyContin to make it “abuse-deterrent.” The reformulated OxyContin is almost impossible to crush and inject, so OxyContin lost its attraction among recreational users. However, it wasn’t clear if those recreational users were abusing opioids less as a result of the reformulation or turning to other opioids besides OxyContin (such as heroin) that was still easy to abuse. The reformulation provides a unique opportunity for social scientists like myself to study what policies are effective in reducing opioid misuse. My colleagues and I wanted to know if the OxyContin reformulation was successful in reducing the recreational use of OxyContin and opioid abuse and whether it led to any unintended consequences.

While the aim of our study was straightforward, the execution was more complicated. A lot of people have the misconception that social science research is qualitative in nature. In reality, gathering, processing, and making sense of data are all very important parts of our job. Real-world data is high-dimensional and complex, and we create mathematical models to mirror these complex, real-world scenarios. The process of finding the right framework to answer our research question reminds me of what my undergraduate econometrics teacher used to say about models. In his opinion, all models are wrong, but some are useful. All models, by definition, are simplifications of reality, but they allow us to focus on the most critical aspects of the data relevant to our research question. Simplifications that ignore the less important parts of the overall picture are useful for identifying the main factors that affect the world around us.

For the first few months of our study, my coauthor Daniel Guth, a fellow graduate student from Caltech’s Humanities and Social Sciences Department, and I sifted through over 500 million records of prescription opioid shipments, read books and papers chronicling the opioid epidemic, and built several mathematical models in an attempt to understand how opioid use disorder takes hold and evolves in a community. Much of the data we relied on for this study was only available because of a court case in 2019 that made half a billion records of opioid transactions from 2006 to 2014 publicly available. Before the publication of this data in the new ARCOS (Automated Reports and Consolidated Ordering System) database, researchers were unable to break down the sales of opioids by brand (OxyContin vs. non-OxyContin) or disaggregate the sales to specific locations beyond the state level. The new publicly available ARCOS data supplied a level of detail that enabled us to look at exactly where the OxyContin reformulation had the most impact with respect to misuse and overdose and compare use of the new abuse-deterrent OxyContin with other brands.

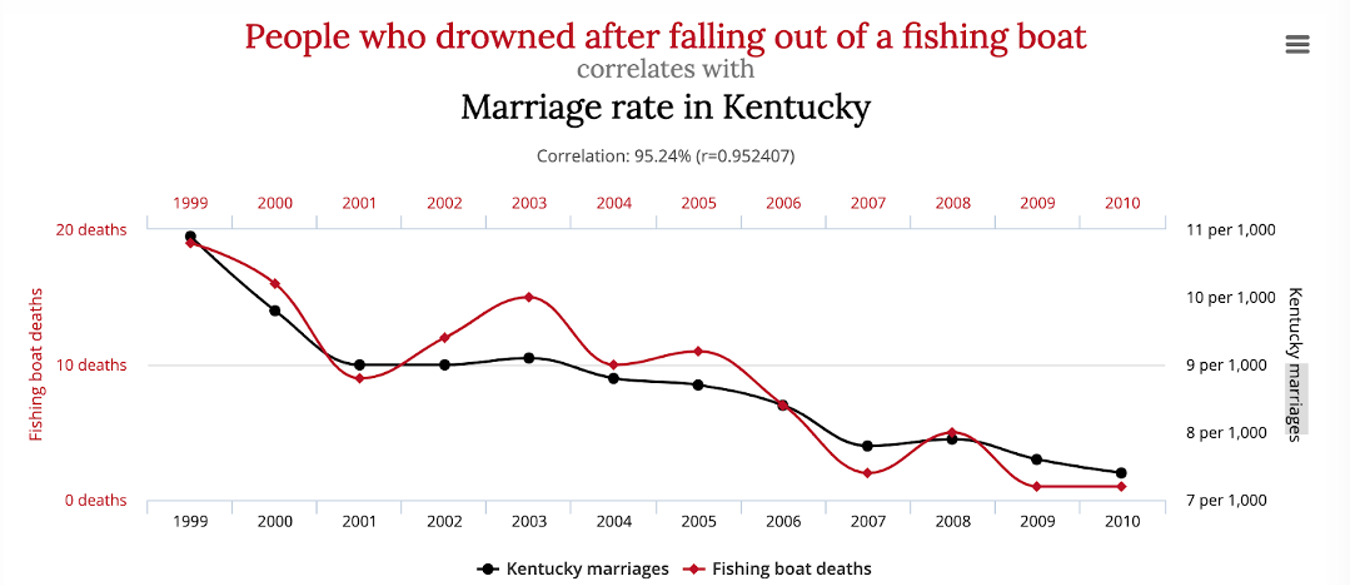

This detailed dataset showed that the sales of OxyContin went down after the reformulation, and the sales of alternative oxycodone went up. Upon seeing this pattern, it is tempting to conclude that the reformulation caused users to switch to a different brand of oxycodone. However, correlation is not causation. Just because two events happened at the same time does not prove that the first event caused the second event. Let me use a simple example to illustrate this point: if you look at the number of people who drowned after falling out of a fishing boat and the marriage rate in Kentucky from 2000 to 2010, you will realize that the two numbers move together over time. Despite what the data shows, it is hard to believe that an increase in marriage rate would cause an increase in drowning or vice versa. Similarly, just because the sales of OxyContin went down and the sales of oxycodone went up after the reformulation does not imply that the changes are caused by the reformulation. To make our claim stick, we need to investigate whether these two events are correlated purely by chance or whether one event causes the other.

An example of spurious correlation.

http://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlation

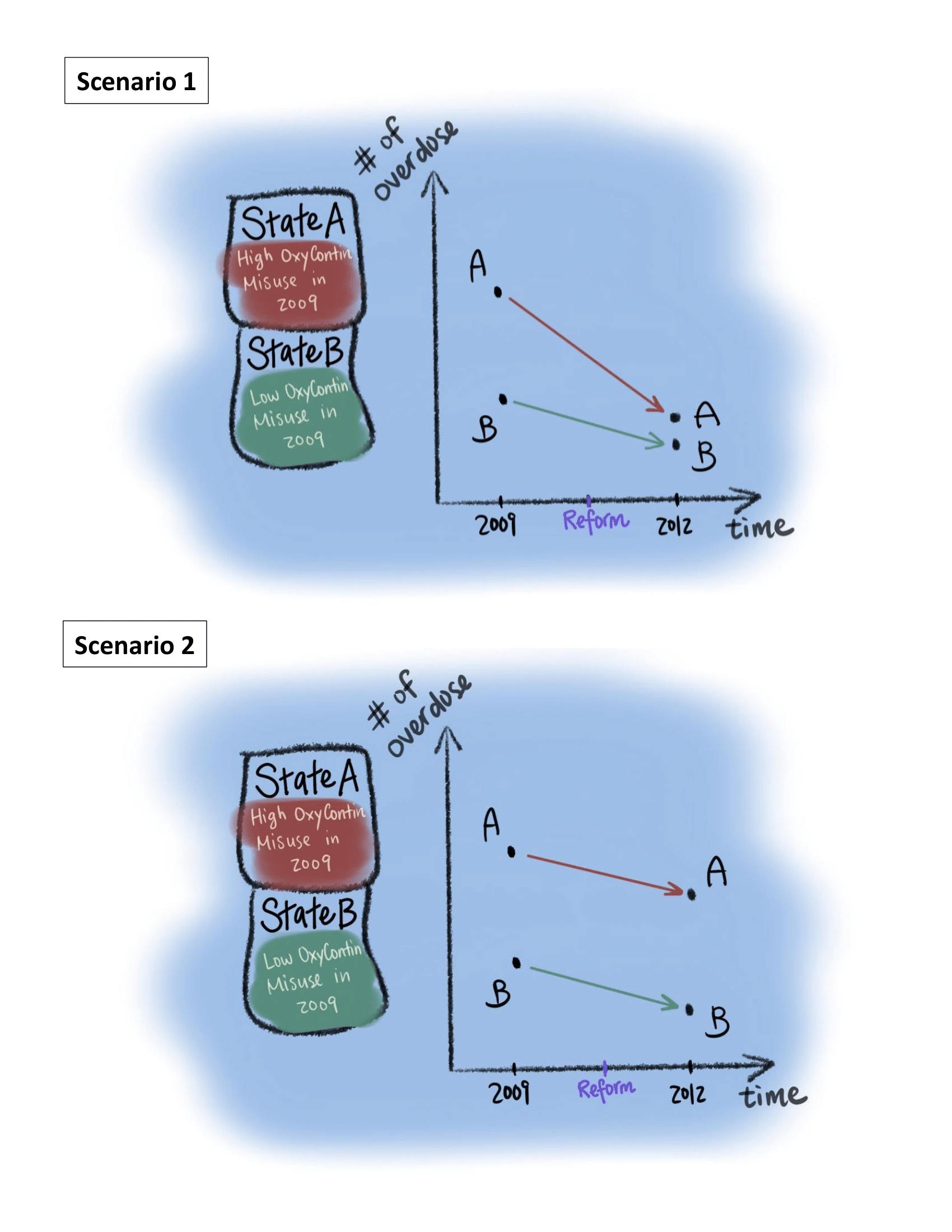

In order to go from correlation to causation in the case of OxyContin reformulation, my team used a common mathematical model in my field called the difference-in-difference (DID) framework. To use the DID framework, we categorize all US states into two bins: those with either a high or low percentage of people misusing OxyContin before the reformulation. If the reformulation truly impacted how people misuse opioids, then the high-percentage misuse group would experience a bigger change in OxyContin usage since there are more people affected by the reformulation. However, if the reformulation had no impact on opioid abuse, then the low-percentage misuse group should experience the same amount of change during this period as the high-percentage misuse group. Hence, by comparing changes in OxyContin usage in both groups we can better assess whether the reformulation was successful in reducing OxyContin use.

Using the difference-in-difference framework to analyze the ARCOS data revealed that our hypothesis was correct.4 The reformulation did indeed cause OxyContin sales to decrease. Additionally, the same model established that the sales of alternative prescription oxycodone went up to compensate. Specifically, in locations where OxyContin misuse was high pre-reform, OxyContin sales dropped a greater amount than where misuse was low, and alternative oxycodone sales went up a higher amount. Because the OxyContin reformulation was a national change uncorrelated with local conditions, this difference-in-difference model provides causal evidence that reformulation caused individuals to switch to a different brand of oxycodone.

Difference-in-difference Framework Example:

Scenario 1: Let us imagine that a state in the U.S., State A is exactly the same as State B except for its OxyContin misuse level in 2009. After the reformulation, State A experienced a higher drop in overdose death than State B. Since everything else between A and B are identical, the difference is likely caused by their initial OxyContin misuse level. Hence, the OxyContin reformulation likely played a part in reducing overdose.

Scenario 2: Let us imagine the same situation as above. After the reformulation, State A experienced the same amount of drop in overdose death as State B. Hence, whatever caused overdose death to drop is likely to be independent of the initial OxyContin misuse level. Therefore, the OxyContin reformulation did not play a part in reducing overdose in this hypothetical situation.

Shiyu Zhang

Although we are addressing very specific questions concerning the OxyContin reformulation, the findings from our study can be applied to develop more effective ways to control opioid abuse. Understanding how OxyContin users responded to the reformulation, a specific example of reducing the supply of an abused drug, can be incredibly informative for researchers and policy makers. These results can shed light on how recreational users of other drugs will respond to reductions in drug supply more generally, whether it is a raid on drug dealers or a change of formulation, as was done for OxyContin. Our study suggests that partial restriction on access to drugs is not effective in curbing use, and a strategy to combat addiction needs to be holistic. It needs to not only cut the supply of illicit drugs, but also connect addicted individuals with the right resources to fight addiction and withdrawal symptoms.6 Even the most well-intentioned interventions may be unsuccessful in curbing drug use, and teams of policy-makers, sociologists, and physicians must join forces to tackle this issue that continues to plague our country.

I would like to think that the research I do at Caltech is both retrospective and forward-looking. In contrast to the work many of my friends do in other departments at Caltech, my research involves building quantitative models to make inferences about social phenomena. While the data I work with and the questions I try to answer concern the past, the inferences I make concern the future. Doing this research for the past year has made me cognizant of the fact that cultural differences in how Chinese and Americans perceive pain medication is not the only driver of the opioid crisis in the US. Rather, the market for prescription painkillers in China is much smaller because it started with stronger regulations. America’s current landscape of opioid use stems from a combination of government policies, pharmaceutical companies, and market forces. In each country or state, the drivers of addiction are complex, and mathematical models can precisely identify those drivers and therefore distill meaningful lessons from our past. The sooner we learn those lessons, the more lives we can save.

References

1: “Overdose Deaths Accelerating During COVID-19.” CDC, December 18, 2020.

2: “Opioid Data Analysis and Resources.” CDC, January 25, 2021.

3: “The U.S. Opioid Epidemic.” Council on Foreign Relations, July 16, 2020.

4: Zhang, Shiyu and Daniel Guth. “The OxyContin Reformulation Revisited: New Evidence From Improved Definitions of Markets and Substitutes.” ARXIV, 2021.

6: Sordo, Luis and et al. “Mortality Risk During and After Opioid Substitution Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies.” BMJ, vol. 357, issue no. 0959-8138, doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550..