On June 16, 2018, a robotic telescope named ATLAS noticed something peculiar in the night sky. There was a new star in the constellation Hercules, and it had become a hundred times brighter in just a few days. Following convention, astronomers named the new star AT2018cow: AT for “Astronomical Transient,” transient meaning a brief celestial event, “2018” for the year of discovery, and “cow” by coincidence; the transients discovered before it were named AT2018aaa, AT2018aab, and so on. It was quickly nicknamed The Cow.

Transients are common. In fact, we’ve known about them much longer than we’ve had telescopes. In 1054 CE, for example, astronomers in China and Japan recorded the sudden appearance of what they called a “guest star.” Across the world, Ibn Butlan was a physician who had recently moved from Cairo to Constantinople. He noticed the guest star, too, and blamed its arrival for the outbreak of an epidemic. Today, we know that the 1054 guest star was a supernova: the explosion of a star, which for a few seconds can outshine the rest of the stars in its home galaxy.

In the modern telescope era, we’ve learned that a supernova is just one kind of transient, and that the universe is a violent place, home to a dazzling array of explosions, collisions, and eruptions. These are so far away that they look like points of light in the sky, just like stars. As a result, it can be hard to tell exactly what you’re seeing: is that new star really a supernova? A black hole shredding a star? An asteroid glinting as it streaks through the solar system? Or—rarely—something entirely new?

The ATLAS team announced their discovery on the The Astronomer’s Telegram, a mailing list for astronomers to report breaking news about the universe. The announcement was cautious. At this point, they acknowledged, we have too little data to tell what this is. Perhaps this was a very ordinary kind of transient. To say for sure, more data was required, so astronomers all over the world dropped everything and turned their telescopes to the same part of the sky.

By now, my email inbox was flooded. Astronomers all over the world were using their telescopes to watch The Cow unfold, and they were reporting spectacular developments. The Cow had gotten even brighter than when it was first discovered, and was officially one of the brightest transients ever discovered. It was 200 million light years away, in a galaxy called CGCG 137-068. A team using the Swift space telescope reported that The Cow was producing bright X-rays. Another team, using a telescope in the Yanshan Mountains near Beijing, reported that The Cow was starting to look like the explosion of a star—but a special one, with material flying out at unusually high speeds, perhaps a tenth or more of the speed of light.

I found out about the X-rays and the high speeds at 4pm, when I was leaving a seminar on cataclysmic variables by a professor at Caltech. I put on my sunglasses, pulled out my phone, and scrolled through my email until I saw the announcement. Then I turned around, walked back into the classroom, pushed my sunglasses up my forehead, and held up my phone to my advisor’s face so that he could see the news for himself.

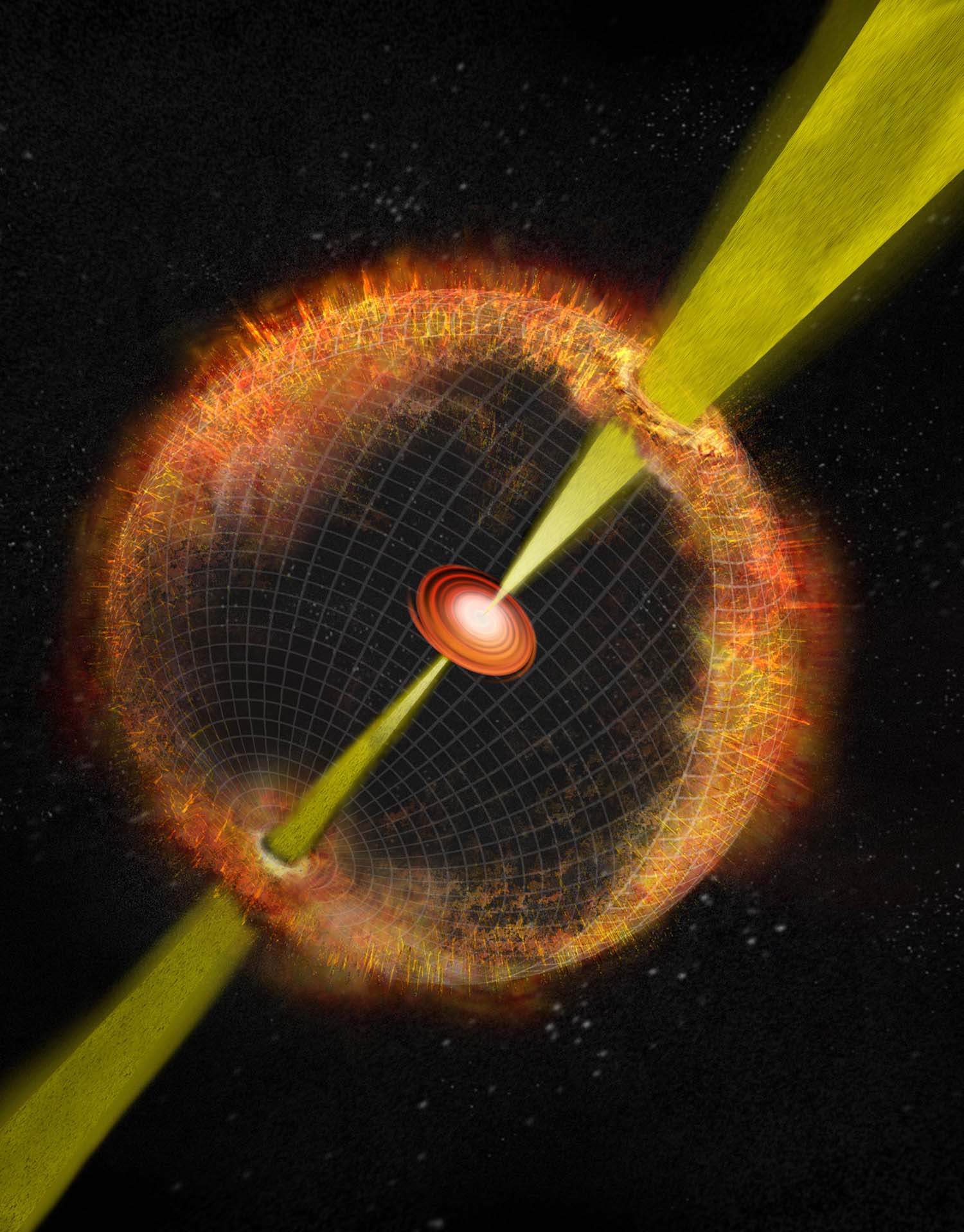

Here’s why I was excited. We know that some stars die violently: they explode, and their core collapses into an exotic object called a neutron star, a teaspoon of which would weigh as much as all the human beings on Earth combined. That neutron star might go on to collapse into a black hole.

That’s the theory, but direct evidence is hard to come by. With modern telescopes, we witness supernovae all the time. Separately, we see the corpses: neutron stars and black holes. To confirm the connection between them, however, we need to find an explosion, and actually witness the corpse emerge in the aftermath. The problem is that the corpse is much fainter than the explosion, and most explosions are too far away for us to see it. So, we rely on a rare case in which the corpse is bright. We call these bright corpses engines: they’re bright because they continue to pump energy into their environment, long after the star has died. X-rays and high speeds are two of the three tell-tale signs of an engine. The only missing sign was radio waves.

Artistic rendering of a cosmic explosion with a central engine.

Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF

To test the engine hypothesis, I needed to search for radio waves and measure their brightness. My colleagues and I decided to use a telescope in Hawaii called The Submillimeter Array, or the SMA, which was designed to see radio waves from space. I went to bed while SMA staff collected the data I asked for; this is standard in modern astronomy, since telescopes are expensive national resources, and it takes special expertise and training to operate them. The next morning, the staff e-mailed me the results. The number was so big—the radio waves from The Cow were so bright—that I thought it was a typo. If this was a supernova, then these would be the brightest radio waves from a supernova, ever. It was not a typo. I emailed one of my colleagues, a professor in the UK, expressing my disbelief. “Yes,” he replied, “it’s madness!”

In the meantime, e-mails kept flooding in. One was from a collaborator asking me to be on Skype at all times. Another was from a professor in my department, saying “Hi Anna, Get some sleep. It has been a long day for you.” There were new announcements reporting bizarre developments. Instead of looking more like a supernova over time, as expected, The Cow was looking less like a supernova as time progressed. For one thing, it maintained a constant temperature, unlike typical supernovae. For another, while most supernovae show characteristics of being a large expanding ball of gas, lit from within, this one didn’t. Actually, not only was this un-supernova-like—it didn’t look like anything that had been seen before.

At this point, my advisor and I discussed whether I should continue working on this. After all, it was no longer within the purview of my PhD project. But I wanted to keep going. So often in astronomy, we are getting new kinds of observations about a known phenomenon in order to learn more about it. A chance to investigate a complete mystery, a completely new kind of explosion—that’s hard to pass up. We observed The Cow almost every night for the next 50 days.

What was The Cow? Nobody knows for sure. From the radio waves, we concluded that whatever it was, it was embedded in a cocoon of gas and dust. These kinds of cocoons have been seen in supernovae, so that suggests that The Cow did indeed mark the death of a star, even though it was different from other supernovae in many respects. In that case, the cocoon was probably created by the star itself before it exploded. This is not unexpected; towards the end of their lives, we believe that stars shed material from their outer atmospheres in violent “death throes.”

We believe that over time, the cocoon became more and more transparent, revealing what lay inside. That something was very much alive: it was producing X-rays that were not only very bright, but which were changing dramatically in brightness from one day to the next. Those X-rays looked similar to what has been seen in active black holes. So, despite the twists and turns, this did in fact seem to be the explosion of a star, resulting in the formation of an engine; very much within the purview of my thesis, but completely different from any kind of engine-driven explosion seen before, and different from anything I had expected to find.

There are other possible interpretations, though, and that’s what’s so mysterious about The Cow. Despite being one of the most extensively-observed cosmic events in history, we still don’t know for sure what it is. It’s like this old parable about people investigating an elephant. In the version from Tales from the Masnavi by Rumi, the elephant is in the dark. One person feels its trunk and concludes that it is a water-spout. One feels its ear and concludes that it is a fan. The leg feels like a tree, and the back feels like a throne. The complete picture eludes them. Similarly, a year on, astronomers are still monitoring The Cow, and there have been a dozen publications by teams contributing different pieces of the puzzle. Any individual piece does resemble an explosion that has been seen before, but it’s difficult to understand them all together. Ultimately, there is disagreement on the interpretation because the combination of properties is so unusual.

For the mystery to be solved, we will likely have to wait for other Cow-like transients to be discovered. The prospects are good. All over the Earth, telescopes in remote deserts and on top of mountains are scanning the sky every night, programmed by humans to find new stars.

The author examining a radio telescope.

Anna Ho

Based on the following publication in The Astrophysical Journal: AT2018cow: A Luminous Millimeter Transient

For more coverage on The Cow, see the following popular articles:

- Washington Post: Could it be a newborn black hole?

- Science Magazine: Astronomers still can’t decipher the ‘Cow’

- Wired: We may have finally spotted a star turning into a black hole

- Scientific American: Holy Cow!