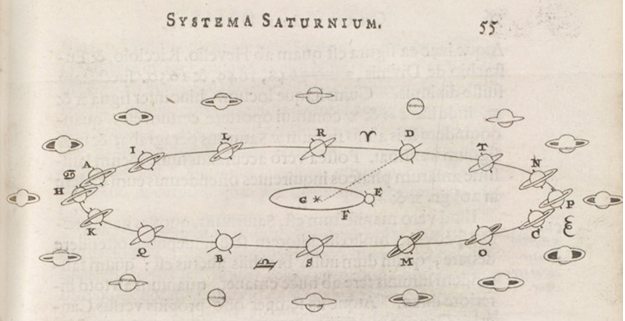

For millennia, the planets in our solar system were thought to be nothing more than wandering stars. Our ancestors observed them as pinpoints of light moving across the sky, unlike their stationary stellar brethren. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that astronomers developed an advanced optical device called a “telescope,” giving us a glimpse of what these wandering stars were and letting us truly see the planets for the first time in history. The telescope revealed the striped patterns of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, and their respective moons, ultimately providing us with the spark to send interplanetary satellites to study them in even greater detail. One can only imagine the wonder and amazement those astronomers must have felt when they first laid eyes upon these alien worlds.

The rings of Saturn as illustrated by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens in his 1659 book Systema Saturnium.

Public domain, obtained from Wikipedia

Today, we know of over three thousand planets outside of our solar system (also known as exoplanets) and that number increases by over 100 planets each year. Unlike the planets we can see in our Solar System, the majority of exoplanets have not been directly imaged. That’s because it’s easier to analyze the light from a star—which is super bright—than to find a hidden speck of light behind the glare of a star. So, for the most part, planets are found by seeing how they influence their star’s light. They may periodically blot out part of the star as the planet passes in front of it, or tug on the star ever so slightly to make the star move, letting us know they are there. But ultimately, what we call a planet is determined from the analysis of graphs and is not light we measure coming directly from the planet.

One of the popular methods of detecting a planet is to look for the dip in the luminosity of the star as the planet passes in front of it. The majority of exoplanets have been detected using this technique.

NASA

The majority of the known exoplanets are closer to their stars than Mercury is to the Sun. That means all those other planets are too close for us to pick them out from the glare of their host star. However, this does not apply to all exoplanets, and astronomers have been attempting to image planets for quite a while now. Not only would it be cool to actually take a picture of a planet outside our Solar System, but we would be able to study the planets directly, and even measure the content of their atmospheres! Of course, it’s not an easy task. The first telescopes were thought to be extraordinary inventions. But for those of us who want to look for worlds around other stars and actually see them, a simple telescope is not enough.

Consider a planet similar to Jupiter, separated from its star by roughly 480 million miles. If the system is 10 light years away from us, then trying to look for the planet is like trying to pick out a firefly flying half a meter away from a giant flood lamp from a distance of 30 miles. Light coming from a planet is usually light that is reflected from its nearby star, and hence a planet is very faint. For every ray of light coming from the planet, you receive a billion rays of light from the star. Of course, the logical step would be to block out the light from the star (flood lamp) to see the light from the exoplanet (firefly). This can be done with a device called a coronagraph–a piece of material meant to block the star’s light.

However, we are not only contending with the glare of the star, but also with Earth’s atmosphere. The light from the star and exoplanet, having travelled trillions and trillions of miles in a straight line through space, enters Earth’s atmosphere and becomes distorted and blurred. It’s as if the light has passed through thousands of different lenses before reaching our detectors. Now, it’s like looking for the firefly from 30 miles away—from the bottom of a swimming pool.

How do you unblur something that’s been blurred? Astronomers use a special type of mirror that bends and shapes itself to cancel out most of the blurring the atmosphere imprints on the star’s light. This deblurring needs to be accurate to within a billionth of a meter to make any difference in the image we want to see! In essence, this adaptive optical trick, coupled with the blocking power of a coronagraph, can enhance the power of a telescope and reveal the light from a planet around a distant star.

When light from a star passes through the atmosphere, it becomes distorted and blurred. Astronomers use a technique called adaptive optics to unblur this light.

Royal Observatory Edinburgh

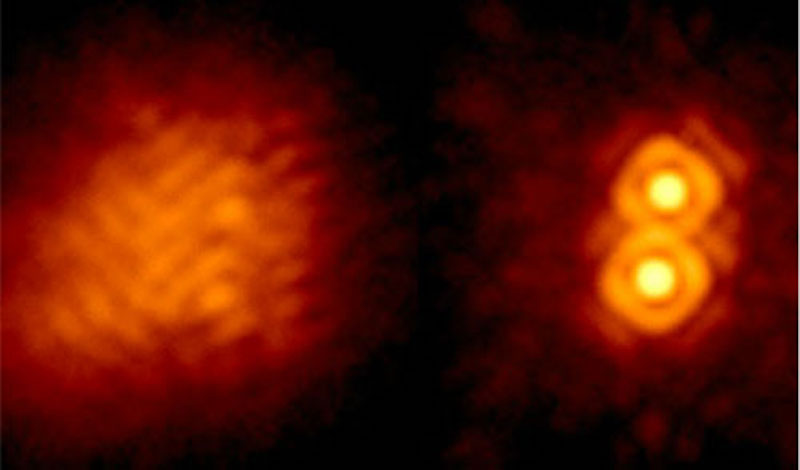

Seen from the ground, the two-star system IW Tau appears to be a single star (left image). With adaptive optics, the blurring caused by the atmosphere is removed, revealing the separated light from both stars (right image).

NASA/JPL

Typically, astronomers who look for direct images of planets target dozens of stars with specific criteria, for instance, they should be nearby, sun-like, or young. Young stars might have young planets that are still forming. Gas giant planets, large planets composed primarily of gas around a rocky core, emit their own light while they are forming, which makes them a little bit easier to detect.

An example of an amazing exoplanet system that astronomers observed was Beta Pic b, around the star Beta Pic. Beta Pic b was discovered using the criteria above, from a large survey study search in 2008, and a combination of a coronagraph and adaptive optics, By “observed”, I mean we could actually see the planet: not as a blip on a graph, but truly witness the light emanating from the planet directly onto our detectors and into our eyes, thereby solidifying the reality of planets around other stars.

We quickly learned that Beta Pic b has eight times more mass than Jupiter and orbits a star with three times more mass than our own Sun. At the time of its discovery, Beta Pic b was one of 300 known exoplanets and one of two whose photograph had been taken. Later that year, another five would be discovered.

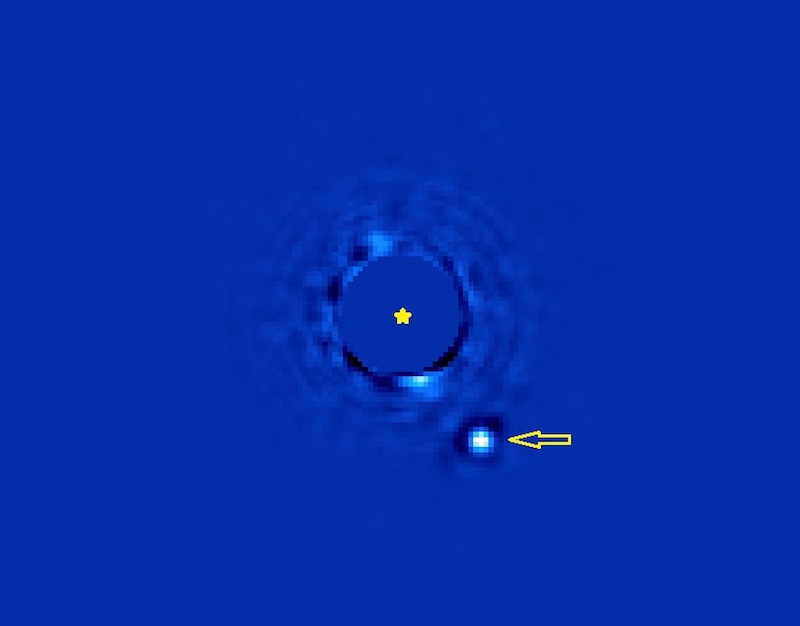

The directly-imaged planet, Beta Pic b, orbits its star at a distance similar to that of Saturn around the Sun, and is 7 times more massive than Jupiter. In this image, Beta Pic b is indicated by the yellow arrow, and the position of the star (which is blocked by a coronagraph) is marked by the yellow star.

NASA/JPL

Over the course of three years, we can see the movement of Beta Pic b around its parent star.

Almost 10 years have passed since the discovery of Beta Pic b, and astronomers have discovered roughly 20 exoplanets using this direct imaging technique. At the same time, these planets have also been moving in their orbits, which we have been able to witness by imaging the planets multiple times over the past ten years. Among the most spectacular of these are the movements of Beta Pic b (above), and the movement of all four planets in the HR 8799 system (below), another planetary system discovered back in 2008 which is so far the only multi-planet directly imaged system.

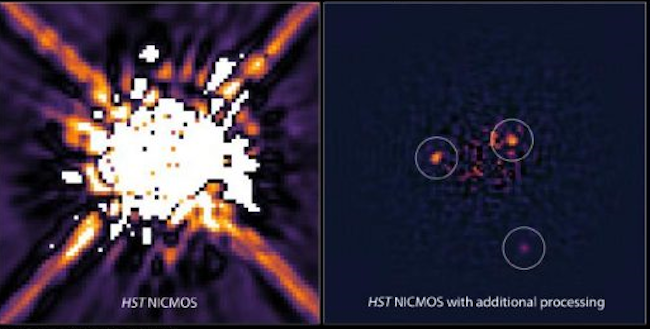

The HR 8799 star system is the only multi-planet, directly-imaged system. In the leftmost panel, we can see how the star overwhelms the image. After removing the star light with a coronagraph, we see the light from the planets (right).

R. Soummer, STSci/NASA/ESA

The movement of a single planet is an amazing sight to behold, but here we can see the four planets of the HR 8799 system trotting along in their orbits around their star! This image shows the motion of the planets over 6 years.

However, these images are not just aesthetically pleasing. All of the currently directly imaged planets are more massive than Jupiter, and young—roughly 4.6 billion years younger than our Solar System! The light we obtain from the directly imaged Jovian-sized exoplanets (that is, exoplanets that are roughly the size of Jupiter) reveals a treasure trove of information related to their composition, atmospheric properties, temperature, and size, which in turn helps us identify their origin and evolution.

Studying these large planets is important, as their massive sizes influence the outcome of smaller planets in the system. Indeed, it has been theorized that Jupiter affected Earth’s evolution in the early solar system. Understanding the formation and evolution of larger planets can in turn help us figure out which systems are ripe for an Earth-sized planet to form and evolve the way ours has.

Of course, this is only the beginning. We will never be content with only imaging gas giant planets. Astronomers are already working towards launching space-based telescopes in the coming decade in the hopes of imaging super-Earth sized or Earth-sized exoplanets. The WFIRST telescope, a planned space telescope with a 2.4 meter diameter mirror, will have an imaging instrument capable of doing just that. Another mission in the works is the StarShade project, which will be able to image an Earth-like planet using a main telescope and an external petal-shaped occulter (used to block out the light from the neighboring stars), driven by its own thruster system.

As a civilization, we have strived to expand our understanding by building better instruments. As the early astronomers built magnificent telescopes to reveal the beauty of the planets in our Solar System, we have expanded upon that invention by improving its resolution and imaging capabilities of faint objects from the ground. To see a gas giant exoplanet around another star is as mind blowing to us as being able to see the rings of Saturn through a telescope once felt. We can only imagine what it will feel like to be the first in human history to lay eyes upon the light from an Earth-like planet.

This article was amended on 02-17-2020 to reflect the fact that Beta Pic b was not the first directly imaged exoplanet