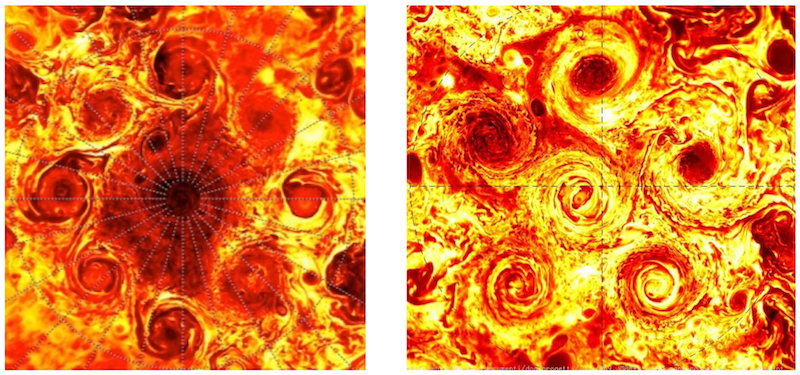

“Wow!” A gasp of amazement spread across the classroom as everyone stared at the latest Jupiter images from the Juno spacecraft, which had thus far been viewed only by the Juno mission team. The neatly arranged storms at Jupiter’s north and south poles looked more like a bouquet of roses than a planet’s surface. We’ve known for a long time that Jupiter is home to giant storms – the most famous being the Great Red Spot, which has raged on its surface for over 150 years – but these latest pictures of Jupiter, taken a few months prior, were something completely new.

At the north pole, Juno saw a central cyclone surrounded by eight storms arranged in an octagon formation, as shown in the image below. On the south pole, it saw five storms arranged in a regular pentagon surrounding a central cyclone.

Infrared images of storms on Jupiter’s north pole (left) and south pole (right).

Adriani et al., 2018, Nature

What makes these images special?

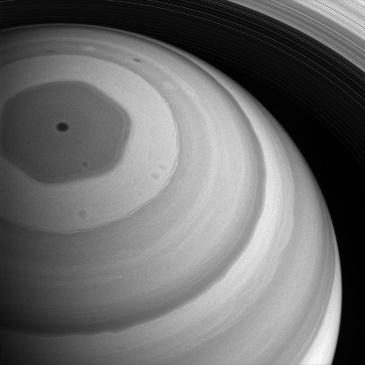

We haven’t seen storms like this on any other planet in the solar system. The only thing that comes close is the hexagonal jet-stream on Saturn’s north pole. This six-sided feature seems to act like a barrier between two distinct parts of the atmosphere. The clouds inside the hexagon are darker, indicating that these clouds are lower. The black dot at the center is about the same size as the individual storms on Jupiter. There is still much we do not understand about these storms, such as how they originated, how they are stabilized, and why there is only one on Saturn, but many on Jupiter.

The hexagonal jet-stream on the north pole of Saturn, as seen by the Cassini spacecraft.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

A hurricane on Earth typically lasts a week, but storms on Jupiter appear to be much longer-lived. They can last for centuries and be larger than our entire home planet. The wind speeds can reach up to almost 400 miles per hour – that’s twice as strong as a category five hurricane!

How did we find these storms? And why haven’t we seen them before?

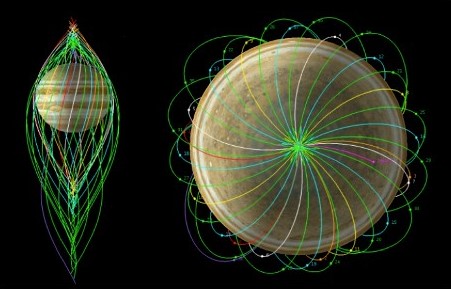

These incredible images are the result of NASA’s Juno mission. Juno is a solar-powered, spinning spacecraft that entered orbit around Jupiter in 2016. It plans to complete twelve 53-day orbits in a highly elliptical path designed to minimize the time spent in Jupiter’s intense radiation field.

Juno is the ninth spacecraft to visit Jupiter, but it is the first to discover these polar storms due to its unique orbit around the planet. Previous spacecraft have stayed in the level with the equator in order to visit the planet’s moons or go on to other planets, and were therefore unable to image the planet’s poles. Juno, in contrast, views a vertical slice of the planet from pole to pole with each orbit.

There are multiple instruments aboard Juno that allow us to see Jupiter in different lights. The pictures below are derived from data collected by the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument. The JIRAM instrument combines an infrared camera and spectrometer to obtain high resolution images of Jupiter’s atmosphere. Its color scale indicates thermal emission. JunoCam, an optical camera whose primary purpose is to take pictures that inspire the public, shows us the storms as we would see them with the naked eye.

Images of Jupiter derived from data collected by the JIRAM instrument, which is composed of an infrared camera and spectrometer. The green lines show the path taken by the Juno spacecraft as it orbits Jupiter from a side and top view.

NASA/JPL/Caltech

My journey to Jupiter

I came to Caltech wanting to understand other worlds, primarily exoplanets, or planets that orbit stars outside of our solar system. However, being in a planetary science department has helped me realize that [1] our own solar system contains a whole host of worlds more weird and wonderful that I had previously appreciated and [2] we can go and visit these places through space exploration missions!

In my first quarter at Caltech I was lucky enough to have a class with Andy Ingersoll on the Cassini and Juno missions. The Cassini spacecraft, which ended its journey last year, provided a wealth of knowledge about Saturn and its moons. We learned that Enceladus has icy plumes erupting from its surface, and Titan is covered in lakes of liquid methane. Though the Cassini mission has ended, the Juno mission is ongoing and continues to provide unique insights into the origin and evolution of Jupiter.

As I learned more about the Cassini and Juno missions, I became increasingly enthralled with the solar system, but it was the Jupiter storm systems I have described that really blew my mind. I began working with Cheng Li, a postdoctoral researcher in the Planetary Sciences department at Caltech, to model these storms and thereby explore them in more detail. The goal of the computer simulation we use is to recreate stable storm systems like those that we see in the Juno images of Jupiter’s south pole. The model incorporates the forces that act on the particles in the storms, such as pressure and the Coriolis force (a force due to Jupiter’s rotation), and calculates the speeds of those particles over a 200-day period. From these calculations, we can see how the storm systems will change over time. In addition to predicting their behavior, our models provide further insight into the origin and characteristics of the storm systems.

What next?

As with all scientific discoveries, Juno’s observations have provided us with more questions than answers. Why are there eight circumpolar storms in the north but only five in the south? How did these storms emerge? What conditions enable these storms to be stable? How long have these storms been there? How deep do these storms extend into Jupiter’s atmosphere?

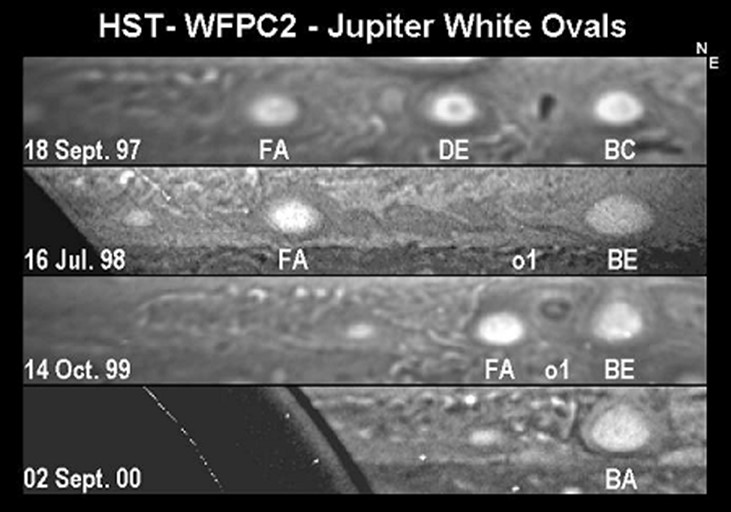

So many questions and so much exciting research to be done! Current literature tells us that storm systems can showcase a range of different patterns. For example, under some circumstances storms merge together, like we saw with the so-called White Ovals on Jupiter. This string of three storms merged over a three-year period, as shown in the image below. Conversely, other storms on Jupiter are stable for hundreds of years. The Great Red Spot, the most famous example, is sustained by swallowing smaller storms.

These Hubble Space Telescope images show how the three "white oval" storms have merged into one over a three-year period.

NASA/JPL/WFPC2

Our models of the pentagonal storms at Jupiter’s south pole, together with current understanding of storm patterns, will help us further explore these storms and begin to answer some of the questions that Juno’s images have provoked. The Juno mission has reminded us that there is still so much we don’t know about Jupiter, and this mysterious giant planet continues to surprise us with each new image we see. I’m inspired to keep studying the largest planet in our solar system by the promise of the wondrous unknown.