Illustration by Sarah Zeichner for Caltech Letters

Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

The drone shattered the afternoon silence as it rose whirring into the air, capturing a panoramic view of our field site in the Anza Borrego desert, less than one hundred miles from the US-Mexico border. After forty minutes of troubleshooting in the sweltering heat, the sound of a functional drone brought feelings of relief. Closer to the border, drones play a much different role and evoke a very different feeling. The tension between these potential drone-provoked feelings represents one of many examples we were trying to explore on this trip.

I am no stranger to dichotomy. I am a geologist, specializing in geochemistry, and an artist; these two distinct aspects of my identity shape the way I see the world and also enabled my participation in this project, Incendiary Traces, led by Professor Hillary Mushkin at Caltech. For this part of the project, a group of geologists and artists traveled to the desert to explore artistic versus scientific methods of observing and recording landscapes.

Cecilia Sanders, a geologist and artist on the Incendiary Traces field trip, flies the drone.

Photo by Gina Clyne, provided by Hillary Mushkin on behalf of the Incendiary Traces project.

Artists and geologists hiking during Incendiary Traces.

Photo by Gina Clyne, provided by Hillary Mushkin on behalf of the Incendiary Traces project.

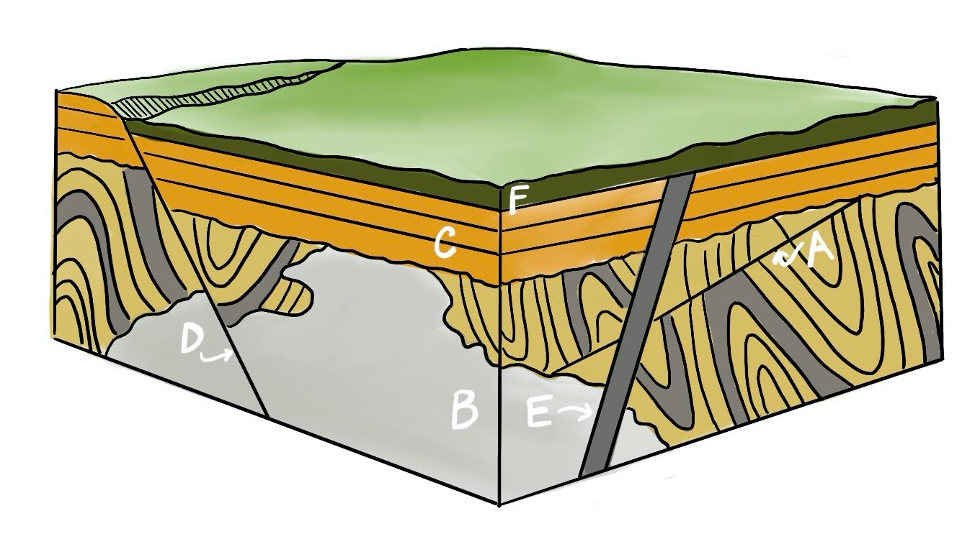

Art and science both share the ultimate goal of storytelling, whether it be of a landscape, a civilization, or a natural process. Yet, science is typically seen as an “objective” perspective on natural processes, while art chooses to engage more overtly with the complex dynamics among nature, society, and politics. Scientists frame observations of the natural world within known scientific paradigms and principles. For instance, geologists use “cross-cutting” relationships to interpret the connection between rocks in an “objective” way: younger rocks get laid down on top of, or penetrate into (in the case of molten magma) older rocks. Understanding the transitions in these strata, or rock layers, allow us to reconstruct Earth’s history over billions of years.

A cartoon of cross cutting relationships between rocks, as taught in introductory geology classes. Original sedimentary layers (light brown and grey) are first laid down in flat layers, then transformed over millions of years. A fault (A) cross cuts those layers, and then they are intruded (B) by molten rock that slowly cools. More sediment is deposited on top (C), followed by another fault (D) and intrusion (E). Each of these layers is referred to as a “stratum,” and a series of layers is described as a stratigraphic column. Modern sediment will be deposited on ancient strata (F).

Image drawn by Sarah Zeichner, adapted from Wikipedia.

The biological and geological worlds are closely linked, but biology defines relationships in a different way. For instance, models of biological interaction describe symbioses between individuals living together in a community. These symbioses can be beneficial for both parties (mutualistic), can neither help nor hurt either party (commensal), or can benefit one party but harm the other (parasitic).

To understand geological or biological relationships, scientists must travel around the world—often into extreme environments—to collect data. The results of these studies typically focus on the scientist’s perspective exclusively, rather than engaging with the political, social, and environmental contexts of the world they’re studying. While doing field work, scientists inevitably affect the places where they are working. Most literally, geologists consume things like food and water and collect valuable natural samples. Though this consumption is theoretically beneficial for everyone, it has the potential to harm the natural environment or people living near the sites. Usha Lingappa, a geobiologist studying the origin of photosynthesis and an artist on the Incendiary Traces trip, expressed concern about the interactions between geologists and their field sites by drawing a parallel to the models of biological interaction: “at best, most field geologists are neutral in their presence. At worst, I think we can verge on parasitic.”

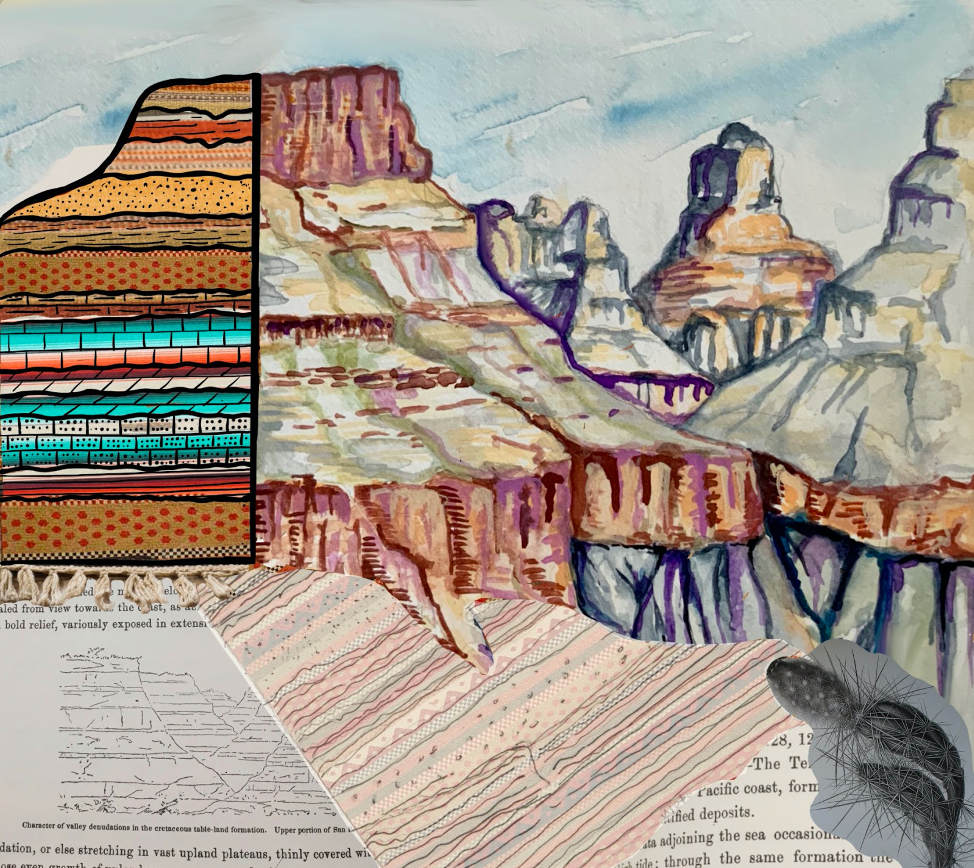

In contrast, art works to challenge the viewers’ perception of the world around them, what they know about it, and how they understand their role within it. It acknowledges the impossibility of objectivity and the inherent role of both the artist and the audience in the work. These distinctions made it obvious to me, even before the trip began, that scientists and artists would ask distinct questions of their field sites. Indeed, the entire purpose of the Incendiary Traces project was to tease apart these dynamics in the Anza Borrego desert. Our site in Anza Borrego has a rich history of documented geologic formations and native plants. But being so close to the US-Mexico border, this rich natural history co-mingles with a tangled socio-political history. The original geologic survey of the Incendiary Traces field site, the US Mexico Boundary Report, was generated between 1857 and 1859. The goal of the original report was to use systematic techniques of observation and measurement to produce an objective record of the “natural properties”—plants, rocks, animals, and native populations—and potential resource value of the newly ceded territory for the US government.

One hundred fifty years later, the Incendiary Traces artists produced different images of the same landscape, with goals of including subjectivity, emotion, and interpretation in the work. For instance, along with hand-drawn images similar to those in the boundary report, drone footage enabled a new perspective of the landscape. Geologists often employ instruments like drones for scientific surveying, but this technique is politically charged and can evoke thoughts of surveillance for people living nearby whose stability and citizenship are in flux. Science can potentially be parasitic by taking only what is valuable to the scientific question without acknowledgment of the broader context within which the science is conducted.

Incendiary Traces artists produced drastically different interpretations of the same landscape.

Photo by Gina Clyne, provided by Hillary Mushkin on behalf of the Incendiary Traces project.

Acknowledging this tension among the natural, social, and political thus poses key questions for scientists. Are scientists exempt from the broader socio-political context of their work, if the goal is to limit scientific research to observation of the natural world? What effect do we, as scientists, have on field sites, and what are the deeper social and political implications of this effect? Can consideration of additional complexity improve “objective” natural studies? In other words, how can scientists improve their research and presence in the world by considering their science through an artistic lens?

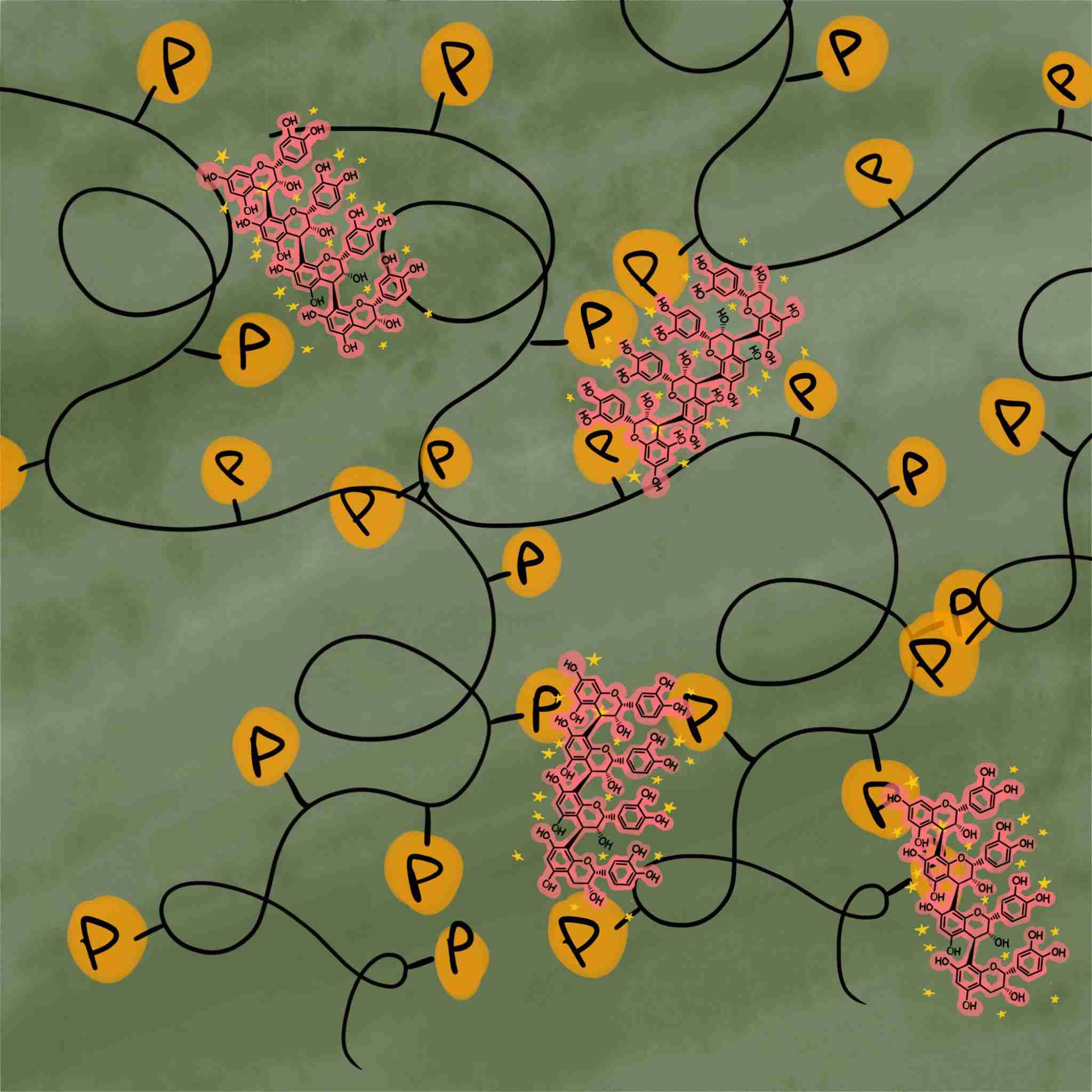

Science is connected to the rest of the world and thus is still nested in its complexities. For instance, science requires funding, which inherently situates it within a broader social and political context. As a geochemist, my research characterizes chemical patterns in carbon-based molecules that have been found on meteorites and in ancient rocks to try to understand their formation prior to the origin of life. The petroleum industry relies on a similar understanding of biomolecules, as oil and gas originate from deposits of ancient biomass. My own research motivations exist beyond those of the petroleum industry, but my work itself is not immune to its influence, and relies on its past research discoveries. Naming funding sources within published work is required, and also a step towards acknowledging potentially subjective opinions, influences or agendas behind the “objective” work.

Context gets more complex as land and natural resources become involved. Field sites are often on Native lands, and samples critical for scientific discovery may be perceived as valuable by other parties, perhaps for cultural or spiritual reasons. Regulations are set up in many places to control the use of geologic and scientific resources and avoid overt parasitism. National parks require permits to take rock samples, and international laws have been set up to regulate specific types of sampling. For instance, the Nagoya Protocol dictates how people can sample biological resources in an effort to regulate and preserve access to them1.

In many ways, permits and regulations acknowledge the complexity and nuances of the political and cultural world that encompasses natural science, preventing exploitation of natural resources that are simultaneously seen as valuable in distinct ways by various parties. A key issue is that scientists typically do not view their field work as potentially harmful. “Geologists don’t perceive the way they use natural resources as exploitative, and they see the permit process designed to target other people, like those extracting mineral resources or land disturbance,” said Ted Present, a sedimentary geologist at Caltech working on reconstructing the conditions of past Earth. He advocates that, beyond being a legal requirement, permits could transform a potentially parasitic relationship into a mutualistic one. “I have come to realize that permits are actually really valuable for us as scientists. The people handling them have valuable local information. If you want to find the one good sample of a specific type of rock, they can tell you exactly where to find it.”

Studying the effects of humanity on the natural world is very much in the spirit of geology; scientists have the potential to benefit the socio-political context within which they are acting, and vice versa. Indeed, human development facilitates geologic research. Road creation and drone technology have allowed broad surveying and documentation of field sites, allowing access to new views of rock strata, or layers. Some areas of geology (e.g., Arctic climate change research) already have begun to incorporate Native records into their research2, as First Peoples have long-lasting and distinct information about how the land has changed over time. In other facets of geological research, including seismological or hazard surveys, the study goals are intrinsically tied to helping communities living near the field sites become more cognizant of the potential dangers of the areas they live in.

Through my own work and the anecdotes of others, I have seen how scientists affect the environments they work in—sometimes positively, sometimes negatively. The world is constantly shifting; as scientists who study the world, we must consider how we can engage with it in a neutral or, ideally, mutualistic way. At a minimum, following government protocols and permit regulations requires us to engage with, and be mindful of, the social and political dynamics at play within our research environments. Explicit land acknowledgements or inclusion of native perspectives within published work offers another way to note the complex relationships among people, sites, and samples, although this is a relatively recent effort within the field of geology. As someone early in my career (and perhaps more optimistic than some of the more cynical, tenured generations of scientists), I believe we can choose to do more. In other fields, paradigms like bioethics have emerged as structured ways to approach these issues; in contrast, geoethics is newer and less-well known and its underlying principles are still being discussed and developed 4.

Scientists think critically about our research and our data—it is time to turn that critical eye on ourselves. We can challenge the norm of science existing in a vacuum, consider the effects of our science on people living in field areas, and explore how we can include them in the work that we do. We can set new precedents and standards for our own research and our collaborations and work to perform future work within a “geo-ethical” context.

Artwork produced during the Incendiary Traces field trip is included in the COLA Exhibition3, which was moved online following the onset of COVID-19 and the shelter-in-place restrictions.

References

1: “About the Nagoya Protocol,” Convention on Biological Diversity.

2: Couzin, J. 2007. “Opening Doors to Native Knowledge.” Science.