“Core on deck!”

The words from the loudspeaker send me into a flurry. Hard hat? Check. Safety glasses? Check. As I race out of the laboratory toward a staircase at the end of the hall, I feel the floor tilt beneath me and use the wall to catch my balance—another reminder that I’m on a drillship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, hundreds of miles from land. My hurried reaction is motivated by a need for good scientific data: if I’m not where I’m supposed to be shortly after this announcement, I may get bad data or no data at all.

I reach the staircase, bound up it, and emerge into a large room buzzing with activity. Half of the 65 total scientists and staff on this ship, the JOIDES Resolution, are busily working in various parts of the room. People stare into microscopes in two corners. Scientific instruments, operated by one or two individuals apiece, line the walls. In the middle, several people stand around a table examining 5-foot-long half-cylinders. These half-cylinders are filled with the literal paydirt of all of this activity: seafloor mud, brought up to the deck of the ship from thousands of feet below the sea surface and more than a mile below the seafloor itself. While unassuming, this mud records some of the most valuable information available on climate changes in Earth’s past.

The JOIDES Resolution, a scientific drilling ship used as part of an international effort to advance our understanding of the Earth's past—and future.

Predicting how Earth’s climate will respond to continued emissions of greenhouse gases is one of the main goals of earth scientists today. Computer models that simulate the transport of heat and matter by Earth’s atmosphere and oceans play a key role in making these predictions. To ensure that these models are accurate, we need to check that they can accurately reproduce events hundreds, thousands, or even millions of years in Earth’s past. But global measurements of weather by humans only go back 150 years, and even the oldest local records only extend back to the mid-1600s. How do we understand changes in climate that occurred long before these earliest human records?

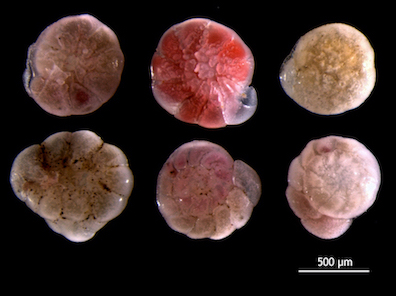

I briefly step into one of the corners where a couple of scientists are peering through microscopes as a staff member on the ship rushes by. “May I take a quick look?” I ask a micropaleontology Ph.D. student who happens to be at the microscope closest to me. He obliges, and I’m presented with a view of hundreds of tiny white and pink shells obtained from the mud—shells that hold the keys to Earth’s climate history.

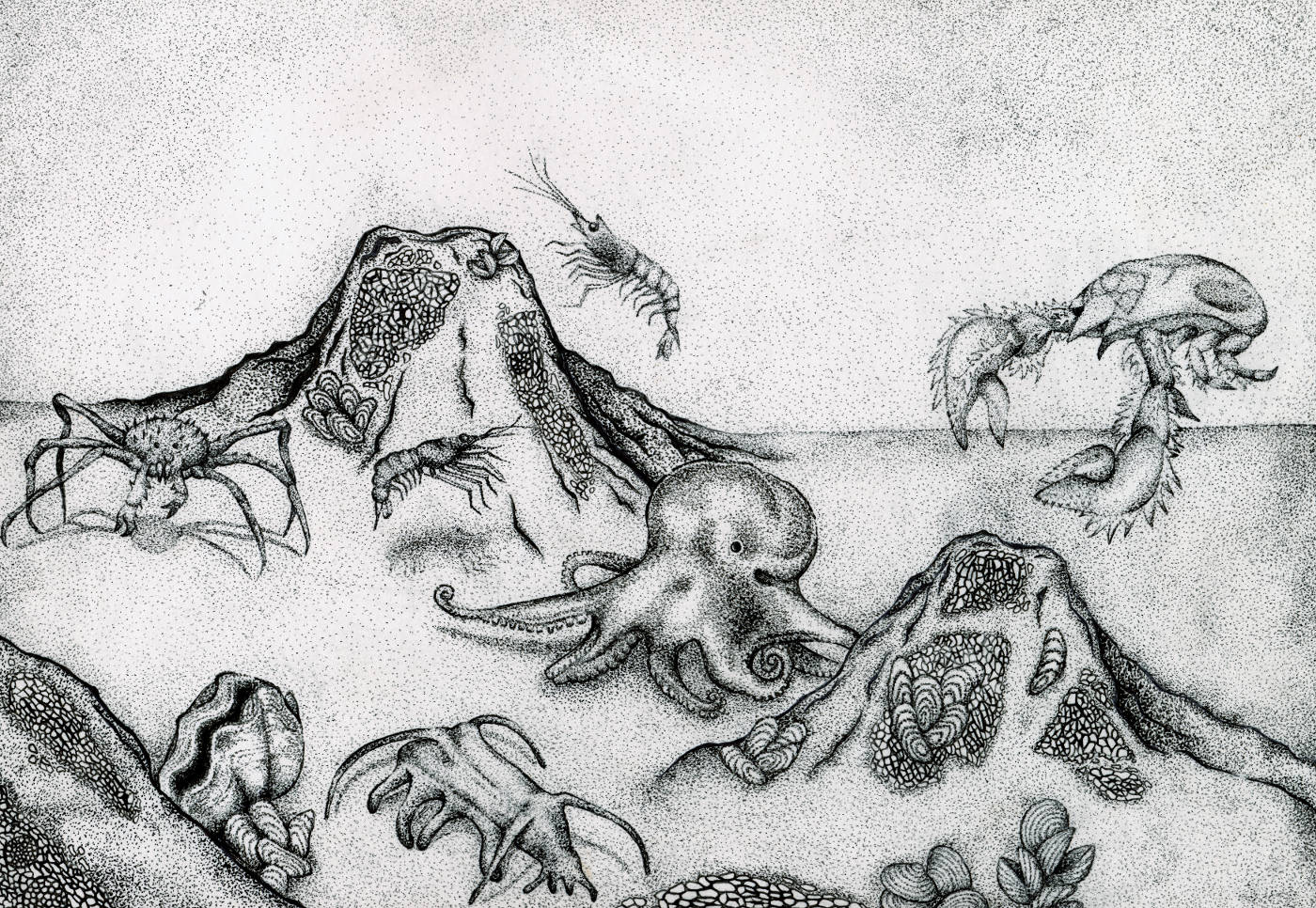

Miniscule shells like these, buried in Earth's ocean mud, hold information about the environment they lived in. By digging them up, scientists can understand Earth's past climate.

Throughout the past 542 million years, Earth’s oceans have been filled with billions of tiny amoebae called foraminifera, or “forams,” that inhabit the seafloor and the water above it. Many species of forams create shells, or “tests,” that are usually about the size of a grain of salt. These shells are typically made of the mineral calcite (CaCO3) and have almost identical chemical compositions. However, small variations in the abundance of minor elements within the tests correlate with seawater properties like temperature—that is, properties influenced by climate. When forams die, their tests fall to the seafloor and accumulate as sediments at a rate of several to tens of feet per million years.

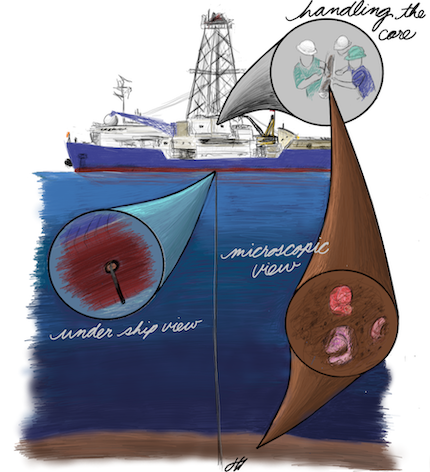

The JOIDES Resolution has the ability to drill deep into the seafloor. Scientists extract water and tiny fossils from the mud at the bottom of the ocean and use it to learn about Earth's past.

Ships like the one I’m on essentially reverse this accumulation process by progressively drilling cores of sediment from the seafloor downward, allowing us to access older sediments and foram shells as we drill deeper. Measuring the chemistry of the shells in the lab then gives us a history of temperature and other seawater properties at the site of deposition through time, letting us slowly build a global climate record with cores obtained from around the world.

A core from this expedition dating back to the Middle Miocene Climate Optimum, a climatic transition more than 14 million years in Earth's past.

Dan Johnson

I step away from the microscope and walk a few feet across the room. Reaching a door on my right, I step out onto the “catwalk,” a narrow walkway on the exterior of the ship. Here I watch as several ship staff bring a 30-foot section of transparent PVC pipe filled with sediment onto the catwalk from the central drilling area on the ship, the “rig floor”. The rig floor is located directly above a small open area in the hull of the ship called the “moon pool.” Sections of metal pipe are connected and lowered vertically through a hole in the rig floor into the moon pool to construct a conduit extending from the ship to the seafloor. A drill can then be lowered through this conduit to allow sediment to be collected and brought back up to the deck of the ship.

The moon pool, shown here, is a hole in the hull of a ship that allows scientific instruments to be lowered down into the water—sometimes all the way to the sea floor!

Integrated Ocean Drilling Program

Obviously, drifting away from a spot on the seafloor while being connected to it with a metal pipe would be catastrophic. To prevent this, the ship has a special dynamic positioning system that uses a combination of GPS measurements and propellers oriented away from the long axis of the ship to maintain the ship’s position to within a few dozen feet.

As the staff reach the catwalk and place the sediment core on a long rack, additional workers spring to life. Amidst a carefully choreographed series of actions, I am handed a two inch slice of core taken from one of the sections and scamper back downstairs to the laboratory.

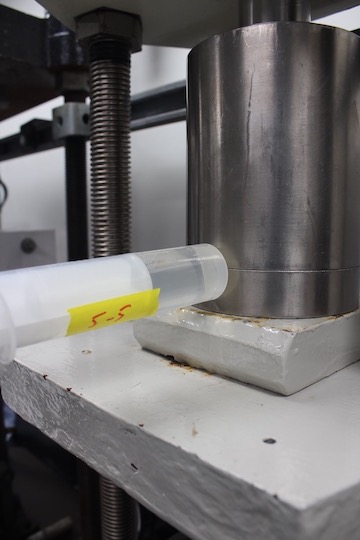

My work begins in earnest upon entering the laboratory. As an inorganic geochemist, my job is to extract water from slices of core and to measure the chemistry of the water using an array of instruments in the lab. Just like mud at Earth’s surface, seafloor sediment is a mixture of solid particles and water trapped within pore spaces between particles. This “pore water” can be squeezed out of the sediments by applying pressure with a hydraulic press. The water contains many ions and compounds that are altered by chemical reactions occurring in the sediment. Because the chemistry of the water may change over time as a result of the drilling process, I must work as quickly as possible. The chemical reactions can also create dangerous conditions for drilling. For example, the breakdown of organic particles in the sediment in the absence of oxygen can create vast amounts of methane gas. Drilling into sediment with very high methane concentrations and allowing the gas to escape into the water above can lower the density of the water enough to cause the ship to sink—something that may have happened at least once in human history.

I place the slice of sediment into the press; within a few minutes, I’m rewarded with a syringe full of water and I begin dispensing the water into storage vials. While most of this water will be used for measurements on the ship, some will be saved for research like my own in laboratories back onshore. I use an instrument called a mass spectrometer, a device that creates charged particles from neutral compounds or atoms and separates them by mass using electromagnetic fields. This device cannot work properly in a moving environment like a ship, but back on land, I hope to measure the abundances of two types of sulfur atoms with slightly different masses—sulfur-32 and sulfur-34—in different compounds within the pore water and sediment.

Water is squeezed from the sediment slice into a syringe. Some of the analysis will be done while on board, but some will have to wait until the scientists are back on steady land.

Dan Johnson

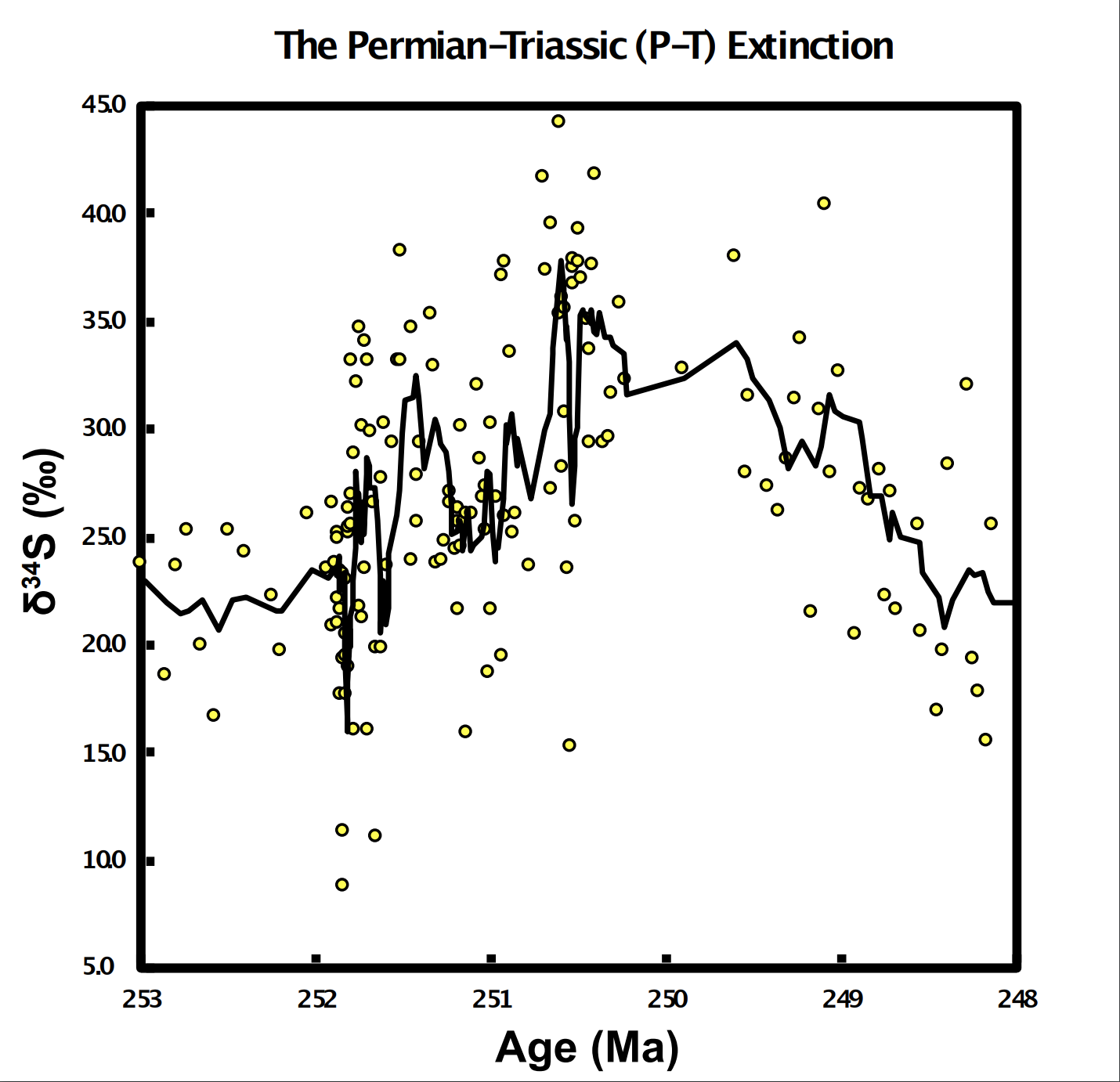

The ratio of these two types of sulfur in seawater has varied throughout the geologic past in a way that is thought to reflect small changes to seawater chemistry—especially how much oxygen was in the oceans at a given time. Changes in climate may beget changes in ocean oxygenation and habitability, so studying these sulfur abundances provides a more complete picture of how life may have been impacted by past changes in climate.

As I finish dispensing water into vials, my mind drifts toward the future. The history of our planet will remain partially shrouded in mystery so long as time machines aren’t available for us to directly observe past geologic events. But by understanding what we can about past climate changes from the sediments we are collecting on this ship, we gain valuable opportunities to anticipate the climate changes that human activities may cause in Earth’s future. These opportunities may motivate actions to mitigate or take advantage of the changes, preventing losses of billions of dollars in the US alone that would occur in the absence of actions.

“Core on deck!”

It begins again.

Further Information

δ34S represents the relative abundance of sulfur-34 to sulfur-32. The increase in this ratio near the time of the Permian-Triassic Extinction (252 million years ago, or Ma) suggests substantial loss of oxygen from the oceans. The P-T Extinction is the largest known extinction in Earth's history.

Figure by Dan Johnson, Data: Song et al., 2014

This video, taken on another drilling expedition, shows a core that captured the time of the dinosaur extinction.

Quick overview of how the JOIDES Resolution operates.