Viewpoint articles are a vehicle for members of the Caltech community to express their opinions on issues surrounding the interface of science and society. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of Caltech or the editorial board of Caltech Letters. Please see our disclaimer.

Science can answer a lot of questions. What shape is the Earth? What makes plants grow? Is there other life in the universe? We have at least partial answers to these questions, and we have every reason to think science will continue to improve those answers.

Then there are other questions… questions science can’t begin to answer. There are questions for which we can’t imagine having answers, questions for which answers might not exist at all.

But there is hope.

In addition to being a scientist, I’m a vegan. (Don’t be alarmed—I’m not here to convert you.)

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

Being vegan has a cost. Many vegan foods are relatively expensive (though Oreos are pretty cheap), and many vegan foods are not as tasty as their mainstream counterparts (though Oreos are pretty tasty). Living in California, I have it pretty easy as a vegan, but in some places, veganism comes with a tangible social cost. Refusing to eat food with a friend is a quick path to isolation.

So… why do it? There are powerful environmental benefits to not eating meat. Those are good, but I personally don’t find them viscerally motivating enough to change my behavior. Some claim that veganism is healthy. I’m skeptical.

What motivates me not to eat animals or their products is the pain and suffering inflicted on those animals. When I imagine the experience of a cow led through a slaughterhouse and weigh that against the pleasure I get from eating a hamburger, there’s no way I can justify the trade.

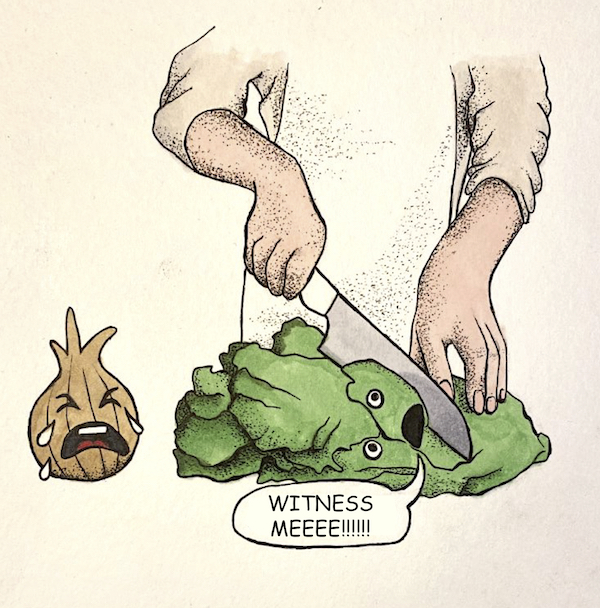

This is convincing enough for me, but it’s a fundamentally flawed argument: how do I know that an animal suffers? How can I know that an animal experiences anything at all? Does a chicken feel mortal terror and excruciating pain when it dies? Does a fish? What about a boiled crab? A crab’s brain isn’t much larger or more complex than a spider’s. Maybe it has no more rich a lived experience than a rock.

Or maybe it does. Maybe both crabs and spiders have rich inner lives. Maybe a spider squashed under a hastily-thrown shoe feels a torment so wretched that you wouldn’t wish it on your worst enemy.

What about lettuce? There are plants that respond to damage by curling up and withdrawing their leaves, and there’s evidence that many plants can identify and cooperate with their relatives. What was the last lived experience of a bowl of lettuce? Did it suffer?

I don’t have good answers to these questions. I’m pretty sure humans are conscious. Consciousness seems to have something to do with our brains. Perhaps an animal with a brain similar to a human’s—like a cow—is conscious enough to feel pain. But this is only a guess, concealing my ignorance.

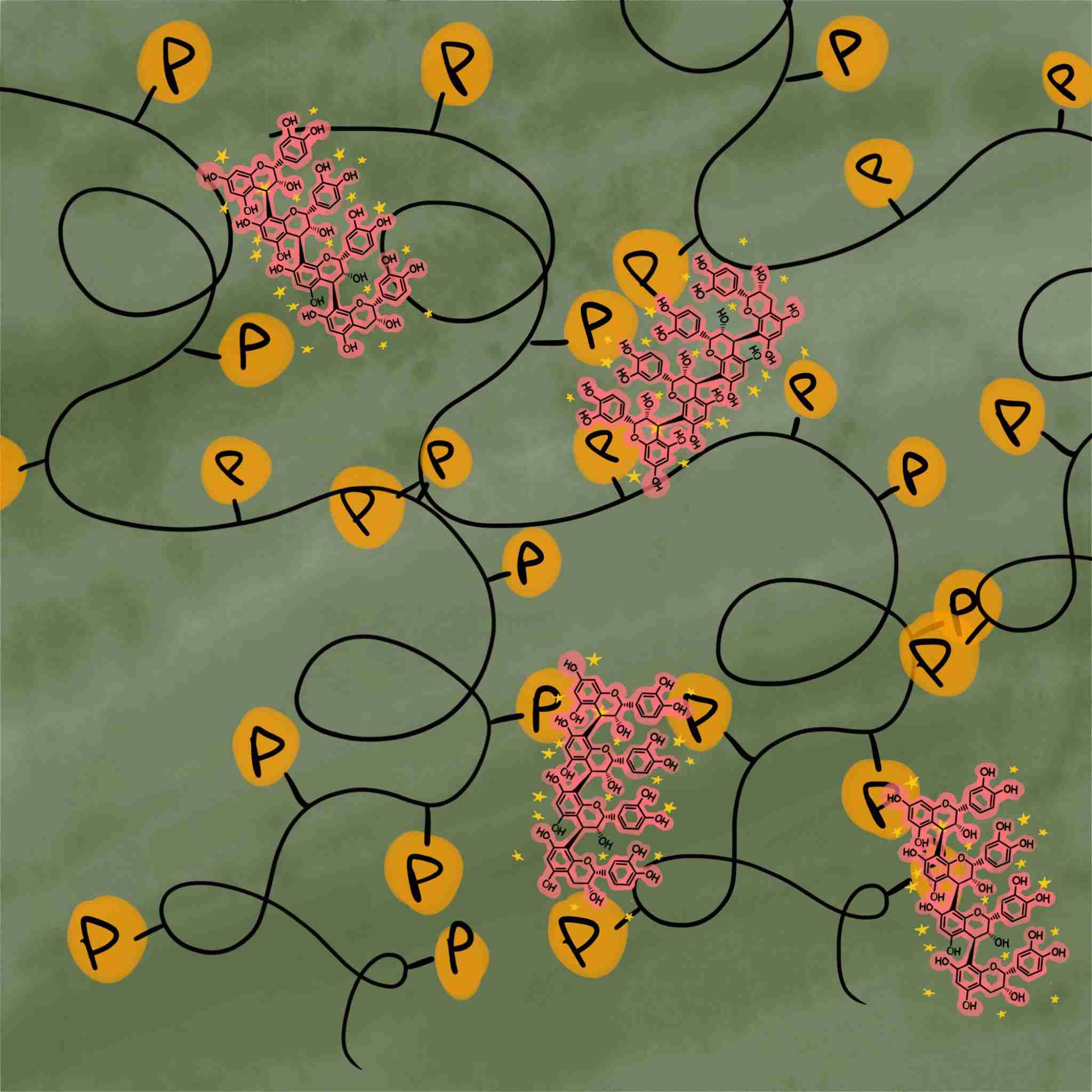

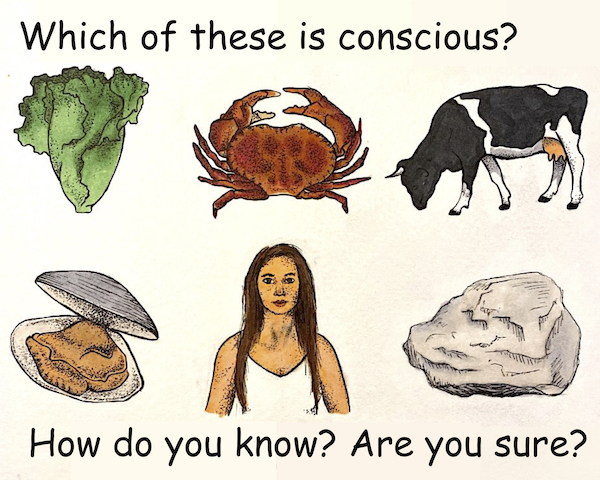

What is consciousness? Why should anything be conscious? Why is consciousness produced at all? How do you know if it’s there?

Philosophers call this question the “hard problem of consciousness”. It is among the most contentious, active areas of modern philosophy.

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

As a scientist, the hard problem of consciousness raises a simple question—what experiment could you perform on an organism that would tell you whether or not it was conscious? Spoiler alert: we don’t know.

That hasn’t stopped ambitious scientists from trying. Experiments on fish pain are typical of scientific attacks on the hard problem. Expose fish to various noxious stimuli, like an injection of vinegar in the lip. Watch for behaviors indicative of pain, like avoidance or compulsive rubbing. Over and over again, we’ve found those behaviors. Therefore, fish feel pain. But do they really signal the presence of conscious experience? It’s not hard to imagine a fish as a machine with built-in programs that cause pain-associated behavior when exposed to the right stimulus, but without any kind of “pain” sensation. We can build a robot that does that, and nobody seriously thinks robots are conscious.

Neuroscientists, on the other hand, are trying to understand consciousness from the inside out—mapping the brain to figure out how it works. And, indeed, we are starting to understand how the physical components of the brain do things like think creatively, control, attention, and lay down, memories. But how does that lead to an understanding of consciousness? What mechanistic model or equation can you write down that you could look at and say “ah, yes, this system must have a conscious experience”? Much as with a behavioral understanding of fish, a physical understanding of the brain seems to predict even humans to be intelligent robots, but without the metaphorical light bulb on.

I, personally, am tempted to say that the hard problem of consciousness is beyond the purview of science.

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

Here are a few other questions that seem unassailable by science: Why is there something instead of nothing? Why does the universe obey precise mathematical laws? Why does it obey any laws at all? Where does a mother’s love come from?

Or what about magnets? Yeah, explain that, science!

Okay, yeah, science has that last one covered. Our scientific models of magnets are precise, quantitative, and predictive. We’ve used them to build all sorts of wondrous technology—speakers, motorized engines, near-instantaneous worldwide communication—soon, maybe even fusion power.

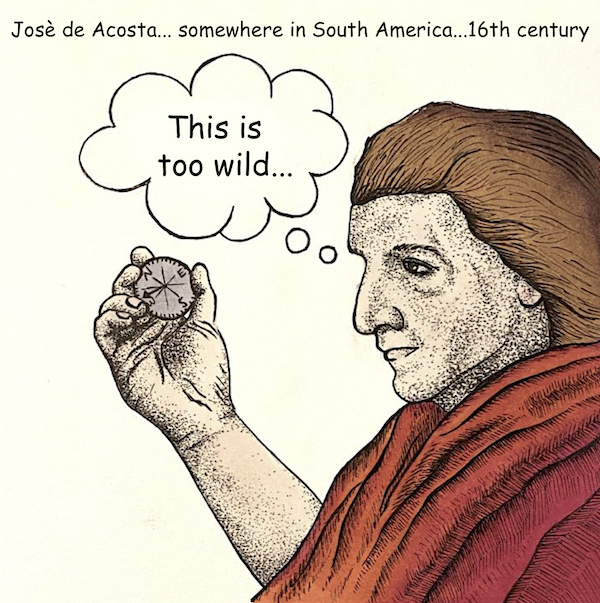

It’s easy to forget that magnets used to be fundamentally mysterious. To our ancestors, it was unclear that rationality or science could ever explain why a compass needle points north. To give you an idea of how unintelligible magnets once were, consider the words of the Jesuit naturalist and philosopher Josè de Acosta, writing about the compass needle in the 16th century:

For my part I would gladly ask university graduates, who presume to know so much[…], why a bit of iron, after being rubbed on a lodestone, acquires the virtue of always pointing north[….] Who can doubt the folly of madness of wanting to make ourselves judges and trying to subject divine and sovereign matters to our puny reason?

Josè de Acosta was a smart guy. He correctly predicted the existence of a land bridge between Asia and America in the 16th century, a time when scholars thought that the people of the new world were the descendants of ancient Greek sailors blown off course by tempests.

Yet, to Josè de Acosta, the magnet was a fundamentally mysterious thing, so impossible to understand that it must be a divine gift granted by God to the Spanish so that they might better navigate the world and spread the word of the Bible.

Josè de Acosta gave up too easily.

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

Science can answer questions even beyond traditionally “sciencey” ones. Consider the question I slipped in about a mother’s love. Why do parents love their children?

Not all do. Some do and yet choose not to take responsibility for them. In our culture, it’s common to view parents who don’t love and care for their children as failures, or perhaps as unnatural or at least unusual cases. But raising a child is a grind. It’s expensive ($233,610 on average, as of 2017). It negatively correlates (albeit mildly) with happiness, marriage satisfaction, and well-being. Parenting has tangible costs. It should be no surprise that some people wouldn’t find parenting worth the trouble. And yet, every year, millions of parents make the choice to have a child.

So… why? Why do any parents love their children?

Could it be because children are cute? But then, wouldn’t we expect every parent to love the cutest child on the block the most deeply? Maybe parents love their children because they resemble themselves? But no, that theory would predict that the truest, deepest love between people ought to be between twins. Maybe we love our children because they give us some hope of immortality, at least in some sideways, metaphorical way. This theory seems more coherent… but then, why do children feel like a continuation of our own lives? Why is that something we would value? For that matter, why don’t we want to die?

Push the question of a parent’s love back far enough and it seems like the answer must eventually be “because, that’s just how humans are.”

But modern science does give us a good explanation for parental love, and for other aspects of human nature. In a word, that explanation is “evolution”.

Evolution is a principle that says that (roughly) if an inheritable trait contributes to an individual’s successful survival and reproduction, then that trait will spread in a population. The theory of evolution was articulated by Charles Darwin as an explanation for things like the diversity of beak shapes and sizes among the finches of the Galápagos Islands. Each island’s finch population had beaks that matched in size and shape to the food on the island. His key insight was that if the Galápagos finches started with a variety of beak shapes, then the birds with the beaks that fit their food would survive better and have more children, eventually taking over the population on each island.

Evolution can also explain human behaviors—even complex behaviors like love.

Imagine a split population. In this population, some parents love their children, and others don’t. The parents who love their children will instinctively see them as people to protect and cherish. Those parents will want their children to thrive, and will give them food, water, shelter, clothes, and other resources, possibly at great cost to themselves. They might take risks for their child. They might even die protecting them.

Human children are vulnerable creatures. It’s possible to survive and thrive without a parent, but it’s harder, less likely. We should not be surprised if, after a generation, more children of the population of loving parents survive than the children of the population of non-loving parents. Parental love, as a trait, will be proportionally more common in that next generation. If it’s an inheritable trait, then those children of loving parents will go on to have more successful children of their own, and the trait will spread further with each generation.

As a parent, you might object to the idea that you love your children “just” because it’s a good evolutionary strategy. Or maybe you’re wondering about adopted children. But evolution doesn’t produce perfectly rational robots that calculate how to best improve their fitness—it produces creatures with traits that contribute to those creatures’ survival and reproductive success. True, unconditional, selfless love is one such trait.

This is what it looks like to solve an impossible scientific problem. The solution—evolution—is simple. It seems utterly obvious in retrospect, even though it took thousands of years of observation, thought, and philosophy to figure it out.

Perhaps most interestingly, this problem wasn’t solved by studying parents or by studying children. We have the key insight, evolution, because Charles Darwin decided to study the beaks of island finches. That single insight has given us answers to innumerable biological questions that would have otherwise been intractable.

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

I don’t mean to imply that all questions have good scientific answers. Some questions are wrong questions, like “Where is the edge of the Earth?” To ask it is to make a mistake. Science doesn’t answer this question so much as dissolve it into nothingness.

Illustration by Emma Sosa, Graduate Student in GPS, for Caltech Letters

What kind of question is the hard problem of consciousness?

It could be a wrong question. It would explain a lot if we’re actually thinking about consciousness in a fundamentally wrong way. It could be that our descendants will look back at us and ask: “Why did they spend time asking such a stupid question? What did they possibly expect to learn?”

The hard problem could also be like the question of a parent’s love—one with a good explanation that just requires an insight from an unexpected direction. If the question simply requires insight, we won’t know this until that insight is found.

Could the hard problem be the kind of question that science can’t tackle, even in principle? The kind that will forever remain mysterious, answers perpetually out of reach?

Maybe. But if you’re tempted, as I sometimes am, to give into despair and declare the hard problem unsolvable, then remember Josè de Acosta and his magnets. Remember how certain he was in his confusion. Remember, too, the countless questions humanity has faced down the ages that, over and over again, we have eventually, persistently, stubbornly figured out.